It was an unusual way for a Vatican official to begin a talk at Oxford University’s shiny new school for public policy wonks: By commemorating a dead cardinal. And even more unusual when the official is a layman.

After beginning with a joke that the Vatican had rather more thick walls and fewer windows than the glass-and-steel Blavatbik School of Government — “but still we hope we are introducing transparency in our own way” — René Brülhart asked the students and professors to observe a moment’s silence for his predecessor as head of the Vatican’s financial watchdog, Cardinal Attilio Nicora, who died earlier this week.

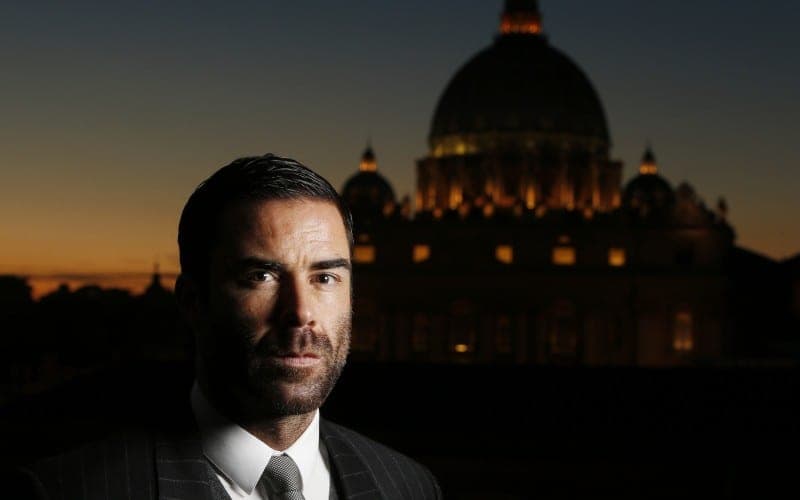

The Swiss regulator, president since 2012 of the Vatican Information Authority (AIF), has had remarkable success in creating and implementing new laws and regulations to prevent Rome’s finances ever again exploding in scandals. After seeing him talk to students of change management, I think I know why.

The auditor — who came to the Vatican after a remarkable success in clearing up that other traditional European money-laundering center, Lichtenstein — is an instrument of reform and change. He should be a major threat to the Vatican old guard, always suspicious of outside experts who think they know best.

Yet that gesture towards his predecessor shows his sensitivity towards the culture of the curia. Many of the questions from the audience, predictably, were inviting him to share stories of the tensions involved, but he never criticized anyone.

He had been given a warm welcome, he said (“walls may be thicker, but people in the Vatican are very warm-hearted”), there was a “big curiosity to learn and understand,” and he was only able to introduce change because of the huge backing from the top he had received.

Brülhart has succeeded in the Vatican in large part because of his sensitivity to its singularity as both a sovereign and global institution. Rather than aggressive talk of “modernizing” the Vatican, Brülhart has sought to create a “tailor-made” system of regulation — a term he used often in his talk — that brings the Vatican into line with contemporary European standards but without sacrificing its uniqueness.

At the same time, he stresses the end of the reform as the good of the institution, the moral obligation to the world’s Catholics to ensure their money is well managed. And protecting Vatican sovereignty: Getting the regulation right means making it less vulnerable to foreign (especially Italian) control.

“There was a big temptation to seek to change everything” when he arrived in September 2012, he told students of government in soft, accented English.

One of Benedict XVI’s two key financial appointments on the eve of his resignation, Brülhart faced a dramatic scenario: The Vatican’s credit card and cash machines had been frozen by the Banca d’Italia, relations between the IOR — the “Vatican Bank” — and correspondent banks had deteriorated to the point where its cash transfers had been frozen.

The IOR’s reforming director, Ettore Gotti Tedeschi, had been ousted, and MoneyVal, the European anti-money laundering watchdog was breathing down Rome’s neck, pressing for change. And unlike Lichtenstein, which mostly passes unobserved, the Vatican financial scandals were assiduously tracked by big global media.

Yet Brülhart moved slowly, keeping a low profile, listening and observing.

“I tried to understand what had happened. How could it happen that cash machines were frozen? I was trying to understand how this could have happened. Who are the key actors? Was the legal system sufficient? Could we execute the work we had to do?”

In 2013 and 2014, what he calls the “building blocks” of Vatican financial oversight were put in place: A new system of supervision, reforms to the penal code, and changes to the AIF’s statutes to give it clear powers of regulation.

Then, in mid-2014, came the new Secretariat for the Economy and the creation of the auditor general role.

“But once you have the legal and regulatory framework in place, then comes the challenge of implementation,” said Brülhart, who is proud of what has been achieved but continually stresses that it’s a “process.”

What has been achieved is easily trackable in the AIF’s annual reports. There were just a dozen information-sharing exercises — when the AIF shares information with regulators in other countries — in 2012, compared with more than 1,500 by the end of 2016. Similarly, suspicious activity reports (flagging up money that might be connected to criminals or terrorists) has increased from just one in 2012 to more than 1,000 in 2016.

IOR funds no longer get frozen.

There is international cooperation. Financial regulations pertaining elsewhere in Europe are applied in the Vatican. For the fifth year, the AIF will in a couple of weeks issue an annual report, and be quizzed on it by reporters at a press conference.

And, of course, the IOR has been cleaned up, not least by closing 5,000 accounts whose holders’ connection with the Vatican was tenuous. It was the existence of these shadow accounts that allowed not just money-laundering but the exploitation —with the connivance of corrupt Vatican officials — of the Church’s financial instruments by criminal, even Masonic, networks.

Now the IOR, says Brülhart, “is now going back to its roots, to its statutes, to what it really stands for, which is serving the Church’s religious works around the world.”

But what about prosecutions? I ask. There has been plenty of cooperation with Italian authorities that has enabled its police to investigate and arrest wrongdoers — but none, so far, in the Vatican itself.

In December 2015, Moneyval complained that there had been “no real results” in prosecutions of financial crimes by Vatican law enforcement, nor even confiscations of assets. There are said to be 40 cases that Brülhart has put on the desk of the Vatican’s chief prosecutor, the so-called Promoter of Justice, but so far without a single conviction.

Brülhart says the current reporting system really only started to work in 2013-14, meaning that the AIF probes suspicious activity reports and where it finds evidence of wrongdoing, passes the case onto the Promoter of Justice.

Brülhart doesn’t say so, but many fear that these cases — fiendishly complex, as white-collar crime tends to be — lie beyond the competence of the Promoter of Justice, which lacks the resources and the know-how to prosecute them.

But then Brülhart surprises me: He will be announcing soon that there have been the first prosecutions for financial crimes. “In the last year we have started to have the first prosecutions, and I’m not talking about dozens, but we’ve taken our first steps, it’s a process but this has been addressed, and we will publish the relevant figures very shortly.”

He agrees with MoneyVal that this is a “key issue.” If, as a result of the new regulatory framework, no one ends up being prosecuted, there is little point. “It’s started somewhere and it has to end somewhere, you have to play the whole chain,” is how he puts it.

But while there are such obstacles — “sometimes there are stones and mountains” — Brülhart never makes the mistake of seeing himself as against the system. “It’s a path we’re on together” is how he describes it.

So what lessons — he is asked — can he share about leading change in established institutions?

Brülhart begins by exhibiting the attitudes that have won him friends in Rome — he’s not the reformer, he is “just a humble servant,” change is teamwork, and so on. Nor does he mention the pope, or make out that all is driven from the Santa Marta. The key driver of transformation, he says, is that it’s the right thing to do — which is why he doesn’t think that it will unravel under a future pope.

That said, he did have two suggestions.

The first was to communicate constantly, building bridges by explaining clearly what you are doing and why it needs to be done, and the consequences of not doing it. The main reason for resistance in any institution is fear of losing what you have, of ceding power to another.

Yet once people understand the need of acting, they overcome their fears. “People who block you at the start can become your greatest supporters,” he says.

The second is to “take emotion out of it.” Change always provokes emotional reactions, which are poor guides. His advice? “Go with an objective approach. Be boring. Go with the facts. How can we improve this?”

As a recipe for Vatican reform, it may not be the most headline-grabbing approach to reform. But it’s working.