ROME – Joseph Weiler, a prominent professor of law at New York University and an Orthodox Jew, has said that at a time of high polemics when the religious voice often has been “muted” from the public arena, Saint Pope John Paul II’s social teaching offers a balanced approach to the interaction between church and a secular state.

Speaking to Crux, Weiler said the modern concept of “rights” has been misconstrued in large part by “the excesses of cultural rights at the expense of duty and responsibility.”

“The main medium of political discourse [today] is of entitlement and rights, what I’m owed, what I’m entitled to, what is my zone of liberty,” he said, adding that in the fallout, “the religious voice has been muted” in a battle over whose rights are infringing on whose.

Weiler, who in addition to teaching law is also the European Union Jean Monnet Chair at New York University Law School and Senior Fellow of the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies at Harvard University, is currently attending a Nov. 15-16 symposium on “Fundamental Rights and a Conflict among Rights,” organized by the Joseph Ratzinger-Benedict XVI Foundation and held at Rome’s LUMSA University.

In his comments to Crux, Weiler noted that a contrast is often created between the French concept of laïcité, the insistence on a secular state, and religion, where believers end up pushing back against laws and policies they view as infringing on their religious freedom.

Weiler cautioned that religious people, including Catholics, “should speak on this with humility,” arguing that those in favor of a laïcité-based society are simply “adopting the practices of the confessional state, which was the norm until not too long ago.”

“Laïcité is becoming a doctrine that was imposed in the way that Christianity was imposed under the confessional state. It was bad then and wrong then, and it’s bad now under this new religion called laïcité, or secularism,” he said, cautioning that a laïcité approach to politics and law has in many ways become “Christophobic,” operating with “a Stalinist instinct.”

What is most troubling in Weiler’s view is that laïcité is often confused with neutrality, as if imposing secularism on society and believers means the state is walking on neutral ground – a trend he sees as alive and well in nations such as Italy, France and the United States.

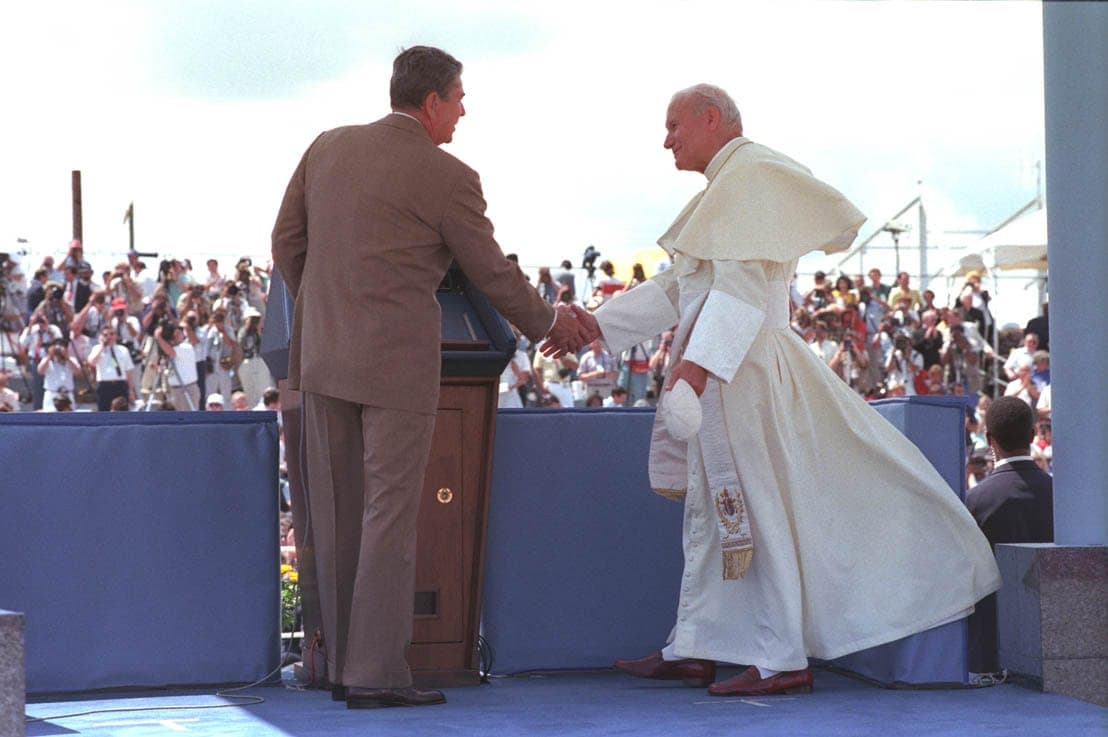

In his view, the right balance in the relationship between a secular state and those who belong to a particular religious confession was found in John Paul II’s 1991 social encyclical, Centesimus Annus, which Weiler said offered “a very, very appealing way to understand the relationship between Christianity and liberalism.”

“The Christianity of John Paul II was not the imposition of the confessional state,” because rather than imposing its positions on others, “the Church proposes…and where there is imposition, it comes from natural law.”

Pointing to the widespread debate over the morality of abortion and euthanasia, Weiler said they are already “rights” in many countries around the globe, yet Christian opposition and the push for their illegalization is legitimate, since for Christians the issue is not a matter of teaching or doctrine but “natural law.”

“They don’t do it because God said so, they do it because it’s the right thing to do,” he said, adding that “when they go into the public place they have to speak in the name of natural law and objective reality,” rather than touting it as simply their own position.

So long as Christians internalize the position of John Paul II and his successor, Pope Benedict XVI, with this approach – proposing and suggesting rather than imposing – “I don’t think they should be reticent in doing so if those are the truths they believe in,” he said.

Weiler, who will give a keynote speech at the symposium on Friday on “Europe’s Identity Crisis as the Crisis of a Reasonable Conception of Human Rights,” said that in his view, the bulk of the problem on human rights, specifically debate over what constitutes a right to begin with, is rooted in “an excessive culture of rights which militates against a sense of human responsibility and human duty.”

Generally speaking, he said that in addition to confusion created over the increasing multiplication of rights, when people read about human rights violations or see them on the news, their immediate thought is “somebody ought to do something about it,” and that somebody is typically always a public authority.

Personal responsibility or action are never part of the equation because the majority “always transfers responsibility of just about every ill in our society to public authorities,” he said, adding that to live only feeling the duty to pay taxes and not break criminal law is “a very impoverished life.”

Weiler said that in his view, there is no remedy for the situation, because “it’s the culture in which we live. We live also in secular societies.”

Turning to the current polemics of American politics, he said that while a sense of entitlement in the U.S. mentality is not necessarily a cause of the current polarization, the deep divides that have come to the fore in recent years have to do “with a long-term process where large sectors of society felt, and with some reason in my view, disrespected.”

“It’s lamentable because the polarization is so profound, and the style of the polemic is so hostile and violent,” he said, noting that when it comes to public debate, conversation is no longer about what’s best for society, but “it’s people screaming at each other and retreating into their tribes.”

Weiler said he has never seen American politics so polarized, describing the current state of political climate as “sad” and “no fun.”