ROME — Professionally described as a historian, professor, Catholic and feminist, some would argue that Italian Lucetta Scaraffia is also a bit of a troublemaker in the Vatican these days. She’s the director of a monthly magazine in the Vatican’s newspaper dedicated to women which, in her words, the power structure “allowed to happen” mostly by not stopping it.

It was an article by her, penned in “Woman, Church, World,” a monthly supplement of L’Osservatore Romano, which led the pope to “break the wall of silence” that has surrounded the question of nuns being sexually abused by priests and bishops.

Scaraffia published an article in the supplement’s February edition denouncing instances in which nuns are raped or abused by clerics, and either dismissed from their religious order or forced into having an abortion if a pregnancy results from the unwanted relationship – or, in some cases, both.

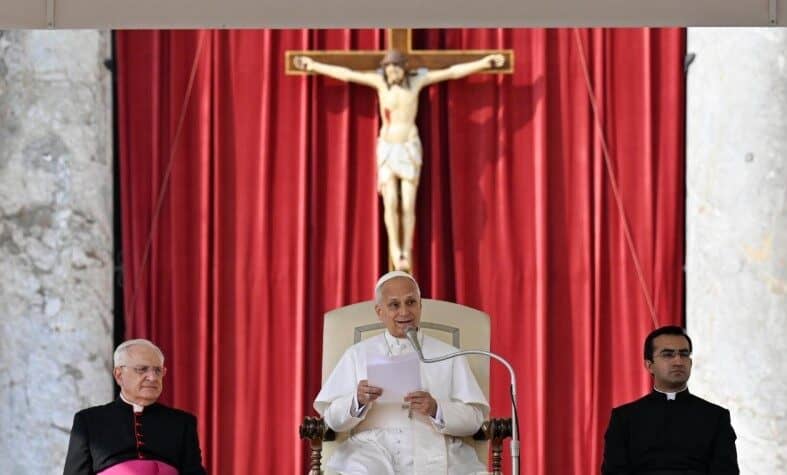

On the way back to Rome from United Arab Emirates, Pope Francis acknowledged that dynamic to be a reality. This, Scaraffia told reporters on Thursday, was the first time the matter was openly addressed in the Vatican.

She said nothing has come of it beyond Francis’s recognition, but she hopes more will result because the abuse of religious sisters “is a very grave situation.”

“Francis is taking some very strong steps, including the acknowledgement of these crimes as a reality, [and] this was courageous,” Scaraffia said. “Up until now, the institution always denied they happen.”

Addressing the situation, she said, is “complex,” for a variety of reasons, including the fact that most of these abuses took place in the past and are virtually impossible to prove.

Though she has a positive view of Francis, when asked if he’s a “feminist,” her answer was a flat “no … Let’s not overreact.”

“I believe the pope is a very political man who understands that women today are a force that cannot be ignored. He’s said it before – service is not servitude. He’s been clear with his words because he knows that we cannot continue as we are now,” she said.

In the past few months, there have been several articles published on the abuse of religious sisters by male members of the Catholic clergy, particularly in France, but the matter was first brought up in 1993, when two French nuns spoke about the abuses missionary sisters were being subjected to in Africa.

In the English language, the earliest reporting was by the National Catholic Reporter in the late 1990s, quoting internal reports prepared by women’s religious orders.

Most allegations currently in the Vatican, Scaraffia said, are old and have been boxed in drawers at various departments for years.

“The Church never accepted taking responsibility, because they thought that if they didn’t speak it could remain hidden,” she said.

Scaraffia highlighted that she’s not in favor of female ordination.

What needs to be changed, she said, is the mentality that equates priesthood with power. If women were to be ordained, Scaraffia argued, they too would “become corrupted by the power of clericalism.”

“For me it’s much more important that women continue being those who oppose power,” she said.

Scaraffia also said that addressing the matter of abuse comes first.

“In the past seven years, I’ve been in touch with many, many religious women, who wrote to us, who we went visit, whom we spoke with, and we realized that this is a huge problem,” she said. “We realized that it’s useless to ask for more places for women in the Church if then, in day-to-day life, so many women are victims of sexual abuse.”

When it comes to the allegations ever being investigated, or the men guilty of wrongdoing paying for their crimes, Scaraffia said that she doesn’t know of any cases. Often, she said, it’s the nuns who pay the price, accused of “tempting” priests and bishops into sin.

Church law, she says, has a provision for abuse, particularly if it takes place during the sacrament of confession, but at the end of the day, abuse of women is harder to prove than abuse of children.

To accuse bishops and priests of past crimes, she said, can be “shameful,” because no law is retroactive and proving the abuse is hard. However, Scaraffia said, “this is a dramatic problem, and this is not any institution: it’s the Catholic Church.”

“It’s an institution founded on one victim, Jesus Christ,” she said. “There’s a big contradiction in the womb of the Church.”

She challenged women to think of themselves as protagonists within the Church.

“Us, women, journalists, Vatican experts, we don’t think if there’s a novelty to ask a woman for her opinion,” she said. “Let’s try not accepting that the Church is only male. Why do we accept that the council advising the pope is only male? We are more than half of the Church, we uphold it, and there’s not a single woman in the ‘senate’?”

“How can they argue the future of the Church is excluding women from the discussion?” she asked.