ROME — Using the media to pray together and, especially, to join others for Mass is showing Catholics that they can be united around the Lord’s table even when they are not physically together, said Jesuit Father Federico Lombardi.

When Pope Francis began inviting a small group of people to the chapel of his residence for early morning Masses, he began with Vatican gardeners and garbage collectors.

It was March 22, 2013, just nine days after his election as pope. Lombardi, who was his press officer at the time, said he soon went to the pope with a request from the Italian bishops’ television station, which wanted to broadcast the Mass each day.

The pope thought about it, Lombardi said, and decided no “because, unlike the public celebrations, he wanted to preserve a more intimate and private character, one that was simple and spontaneous, without the celebrant and assembly feeling like the world was watching.”

With the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown in Italy and other countries, the situation — and the pope’s thinking — have changed, Father Lombardi wrote in the first installment of his “Diary of a Crisis” for the Vatican newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano.

Francis still celebrates Mass at 7 a.m. in the chapel of the Domus Sanctae Marthae, but there are no invited guests, just his secretaries, a few of the sisters who work in the residence, an organist and the television camera operator.

“It is transmitted live and followed by a great number of people who receive comfort and consolation from it,” Lombardi wrote. The viewers unite with the pope in prayer and are “invited by him to make an act of ‘spiritual communion’ because they cannot go forward to receive the body of the Lord.”

When giving a homily, he said, Pope Francis “loves to look in the eyes of those present and dialogue with them,” but now he looks at the camera and the “congregation” hears his voice over the TV set, the internet or the radio.

But his words still “reach the heart,” he wrote. “The assembly is no longer present physically, but it is there and, through the person of the celebrant, is truly united around the Lord who died and rose again.”

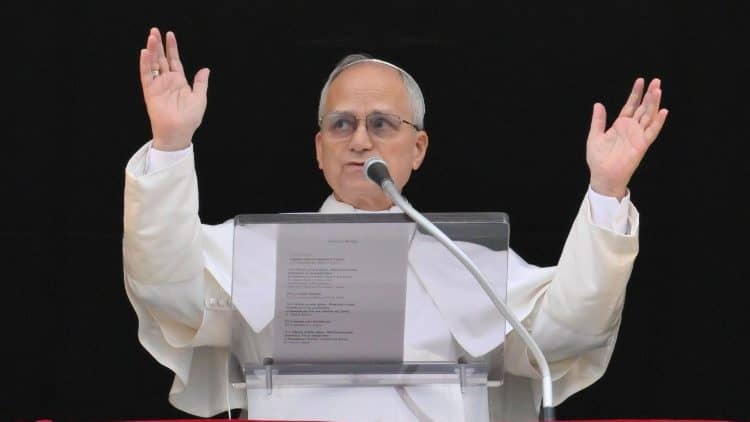

Pope Francis praying in an empty St. Peter’s Square or an almost empty St. Peter’s Basilica is even “more intense,” Father Lombardi said. The Vatican is used to giving crowd estimates — 50,000 or 100,000 or 200,000 for major events — but it always has known that millions more are watching on television.

The reality of those global “gatherings,” he said, were especially obvious during the “Urbi et Orbit” (to the city and the world) blessings of St. John Paul II, who always wished people “Merry Christmas” or “Happy Easter” in more than 50 languages, reading off a page where the words were printed phonetically.

But, Lombardi wrote, Pope Francis’s special “Urbi et Orbi” prayer in late March, praying for an end to the pandemic, and his Way of the Cross service on Good Friday demonstrate that “the pope can be alone in St. Peter’s Square, like in the chapel at Santa Marta, but the church, the universal assembly of the faithful, is strongly real and united by bonds that are very deeply rooted in the faith and in the human heart.”

Even in the empty square, he said, it was obvious people were more present that the word “virtual” would suggest, showing a whole web of “spiritual relationships of love, compassion, suffering, longing, waiting, hoping.”

The church as the body of Christ is a spiritual reality that “is manifest when the assembly is physically gathered and present, but it is not tied to or limited by physical presence,” Lombardi wrote. “Paradoxically, in these days that can be experienced in a stronger and more evident way.”