Whether it’s held in vast countries such as the U.S. in 1993, or tiny ones such as Panama this week, a World Youth Day is always a huge logistical challenge for all organizers – Church, city and state.

Patrons insist that the benefits of organizing a WYD always exceed expenses, and the income isn’t measured simply in spiritual gains. Despite that, steadily fewer dioceses are volunteering to host a World Youth Day, perhaps daunted by the scale of the perceived challenges.

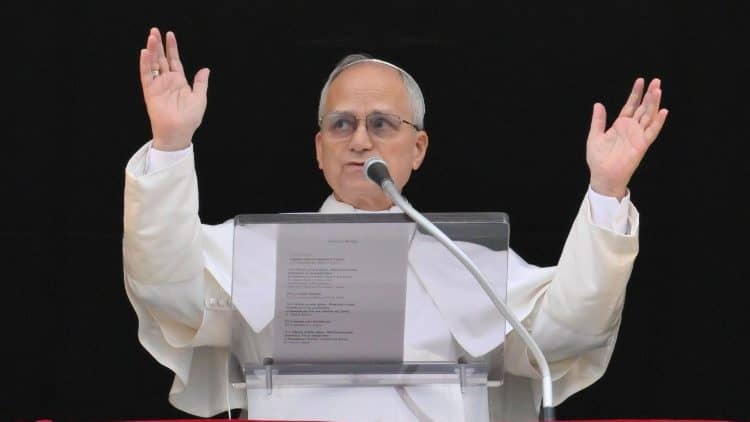

Herewith, a review of WYD myths just days before Pope Francis announces the next host after Panama. (It’s widely expected to be Portugal.)

Myth No. 1 – WYD is super-expensive

A World Youth Day is a huge event, with more participants than any rock concert or Olympic Games. In truth, it’s not just one event but hundreds: in Krakow 2016, there were 12 main events and more than 250 cultural activities.

But if you look at WYD budgets, this international youth gathering costs roughly the same amount as one Oscar award ceremony in Los Angeles. The Krakow edition cost around $50 million, while the 2018 Oscar ceremony (which filled up the Kodak theatre with celebrities for just one night) ran a robust $44 million.

In some cities, comparisons with other events are painful: WYD Rio 2013 brought more or less the same number of people to town as the Olympic Games the following year, but budgets were “slightly” different: $63 million against $8 billion, as we read in Megaevents of the Catholic Church, a handbook written by professionals who worked in four World Youth Days (including this author) and edited by Yago de la Cierva, WYD Madrid 2011 executive director.

For the local dioceses organizing WYD, finding financial means is a gigantic challenge. Krakow’s economic department worked around the clock for weeks, with the accountant literally leaving the office as the event drew to a close at 3:00 a.m. only to come back at 8:00 a.m.

“First is the prayer. You cannot touch the ‘profanum’ without touching ‘sacrum’ first. Second is transparency and accountability,” said Father Wojciech Olszowski, the chief financial officer of the Krakow committee.

More than a third of WYD funding usually comes from pilgrims’ fees. The rest comes from sponsors, the faithful, and the state. Krakow WYD was the cheapest modern WYD, and it even left a surplus of $160,000.

According to Megaevents, in Rio 2013 World Youth Day left a debt to the archdiocese only because the Brazilian government under promised $15 million for infrastructure and never paid.

Myth No. 2 – numbers are key

A great media fuss about any WYD always surrounds a predictable set of questions: How many people are going to attend? What was the size of the crowd during its main events? How many people registered?

“Any WYD experiences the same media attention about registered pilgrims, as if that number was indicative of both the event participation and its success. Actually, it has been a constant ratio in most WYDs that the number of participants at the final Mass can be calculated by multiplying registered pilgrims by four,” Thierry Bonaventura, longtime spokesperson for CCEE and now communications officer of WYD Panama 2019 told Crux.

“People usually flow from local dioceses when they see WYD excitement on TV – that was the case of Madrid, Rio and Krakow, and it will be the case of Panama,” he added.

Father Thomas Rosica, Executive Director of WYD 2002 in Toronto, commented during a press conference in WYD Krakow: “It’s not about a huge number of people attending, but about one person that will be changed by WYD … that’s all that matters.”

In fact, according to Megaevents, probably the best WYD ever organized was in Sydney in 2008, with “only” 300,000 participants at the main events, but it wielded a great impact on local youth and in the whole Pacific area.

Myth no. 3 – the state doesn’t get anything in return

Before WYD 2016, Krakow non-religious Poles were concerned that taxpayers’ money would be “sunk” into WYD – an event organized by the Church, and for the faithful. The Polish government invested around $5 million in the event, including military, police and secret service agents and resources to secure the event.

But that’s only one side of the story. In reality, the Krakow archdiocese paid $10 million in taxes the same year, so the money invested by the states was returned doubled. In the end, only 10 percent of the total WYD budget came from the state.

That’s not the only benefit. Over 90 percent of young people attending Krakow admitted in a post-WYD survey they were encouraged to improve their societies after WYD 2016.

The head of promotion in Krakow, Joanna Zając, said WYD is also a great opportunity for the state to promote itself internationally: “We learned we have youth that are creative, dynamic, open and full of imagination. All those people working around the clock to make WYD happen in every corner of the country stayed here and enriched the job market in Poland.”

Rosica said that WYD is a gift for the whole society and a call for unity.

“We had a staff of 400 people for our WYD 2002, and 295 were young adults from 40 countries and 38 cities in Canada. It was a blessed experience,” he told Crux.

Myth No. 4 – The host city will face Armageddon

“The city will be paralyzed,” Mayor Jacek Majchrowski of Krakow told reporters at a press conference in 2015, a year ahead of WYD. He encouraged inhabitants to leave the city during the time of the event.

Experience, however, proved the opposite.

“Not only was the city not paralyzed, it flourished!” one of Krakow’s inhabitants reported. “I regretted I didn’t take pilgrims to my house – it would have been an unforgettable experience for my kids,” she said.

The event was also secure and calm. Despite the fact that 2.5 million people flooded the city, there was not a single police intervention due to public unrest, and not even a single person was detained for being drunk.

Madrid in 2011 generated a similar sense of good will. The Spanish capital was struck by how clean pilgrims left the city – according to city hall, the amount of waste left by the 2,100,000 pilgrims was one-tenth of the refuse generated by a soccer championship final in Madrid, not to mention a “Gay Pride” parade organized the following year with fewer than 200,000 people.

Myth No. 5 – Communications aren’t all that important

Many organizing committees for a World Youth Day don’t think of communications as a key issue until problems arise. Yet Rafa Rubio, Madrid’s communications director, said that communications not only helped boost registration, smoothing criticism against the pope’s visit and promoting the event, but also helped to overcome major crises.

“During the vigil we had a huge storm, and we had to have different channels open to communicate logistical changes for the final Mass. We had created channels with the pilgrims in social media and we managed to communicate it during the night, so everybody knew first thing in the morning.”

The same thing happened in Rio de Janeiro, when venues had to be changed at the last minute due to weather conditions. Rubio, who worked in Rio as well, said that good communication channels are key.

“No matter how good planning and logistics are – and sometimes they are not good enough – you need to make adjustments to the original plan,” he said. “If you can’t communicate them to a huge crowd, you are completely lost.”

Besides, there is a direct connection between communication and funding. In Madrid, the sponsorship program was entrusted to the communication department, Rubio said, and that was a key element for WYD good finances.

“Communication is not just about spending, but getting public support,” he said.