UYO, Nigeria — Three years after taking in 2-year-old Inimffon Uwamobong and her younger brother, Sister Matylda Iyang finally heard from the mother who had abandoned them.

“Their mother came back and told me that she (Inimffon) and her younger sibling are witches, asking me to throw them out of the convent,” said Iyang, who oversees the Mother Charles Walker Children Home at the Handmaids of the Holy Child Jesus convent.

Such an accusation is not new to Iyang.

Since opening the home in 2007, Iyang has cared for dozens of malnourished and homeless children from the streets of Uyo; many of them had family who believed they were witches.

The Uwamobong siblings became well and were able to enroll in school, but Iyang and other social service providers are faced with similar needs.

Health care and social workers say parents, guardians and religious leaders brand children as witches for different reasons. Children subject to such accusations are often abused, abandoned, trafficked or even murdered, according to UNICEF and Human Rights Watch.

Throughout Africa, a witch is culturally understood to be the epitome of evil and the cause of misfortune, disease and death. Consequently, the witch is the most hated person in African society and subject to punishment, torture and even death.

There have been reports of children — labeled as witches — having had nails driven into their heads and being forced to drink cement, set on fire, scarred by acid, poisoned and even buried alive.

In Nigeria, some Christian pastors have incorporated African witchcraft beliefs into their brand of Christianity, resulting in a campaign of violence against young people in some locales.

Residents of the state Akwa Ibom — including members of the Ibibio, Annang and the Oro ethnic groups — believe in the religious existence of spirits and witches.

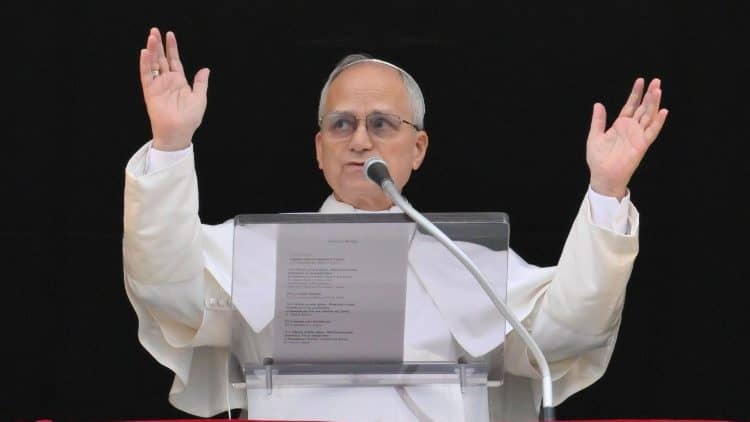

Father Dominic Akpankpa, executive director of the Catholic Institute of Justice and Peace in the Diocese of Uyo, said the existence of witchcraft is a metaphysical phenomenon from those who do not know anything about theology.

“If you claim that somebody is a witch, you would have to prove it,” he said. He added that most of those accused of being witches could be suffering from psychological complications and “it is our duty to help these people with counseling to come out of that situation.”

Witch profiling and abandonment of children are common on the streets of Akwa Ibom.

If a man remarries, Iyang said, the new wife may be intolerant of the child’s attitude after being married to the widower, and as such, will throw the child out of the house.

“To achieve this, she would accuse him or her of being a witch,” Iyang said. “That’s why you’d find many children in the streets and when you ask them, they will say it’s their stepmother who drove them out of the house.”

She said poverty and teenage pregnancy also can force children into the street as well.

Nigeria’s criminal code prohibits accusing, or even threatening to accuse, someone of being a witch. The Child Rights Act of 2003 makes it a criminal offense to subject any child to physical or emotional torture or submit them to any inhuman or degrading treatment.

Akwa Ibom officials have incorporated the Child Rights Act in an attempt to reduce child abuse. In addition, the state adopted a law in 2008 that makes witch profiling punishable by a prison term of up to 10 years.

Akpankpa said criminalizing injustices toward children was a step in the right direction.

“A lot of children were labeled witches and victimized. We used to have baby factories where young women are kept; they give birth and their babies are taken and sold out for monetary gains,” the priest told CNS.

“Human trafficking was very alarming. A lot of baby factories were discovered, and the babies and their mothers were saved while the perpetrators were brought to justice,” he added.

At the Mother Charles Walker Children Home, where most of the children are sheltered and sent to school on scholarship, Iyang demonstrates the Catholic Church’s commitment to protecting child rights. She said most of the malnourished youngsters the order receives are those who lost their mother during childbirth “and their families bring them to us for care.”

For contact tracing and reunification, Iyang formed a partnership with Akwa Ibom State Ministry of Women Affairs and Social Welfare. The process begins with parental verification by gathering information about each child and their location prior to separation. With the information in hand, an investigator drives to the child’s home village to verify what has been learned.

The process involves community chiefs, elders and religious and traditional leaders to ensure that each child is properly integrated and accepted in the community. When that fails, a child will placed into the adoption protocol under government supervision.

Since opening the Mother Charles Walker Children Home in 2007, Iyang and the staff have cared for about 120 children. About 74 have been reunited with their families, she said.

“We have 46 now left with us,” she said, “hoping that their families will one day pick them up or they will have foster parents.”