DETROIT, Michigan — A Detroit priest who focused his ministry on the poor and needy has been beatified, a key step toward sainthood.

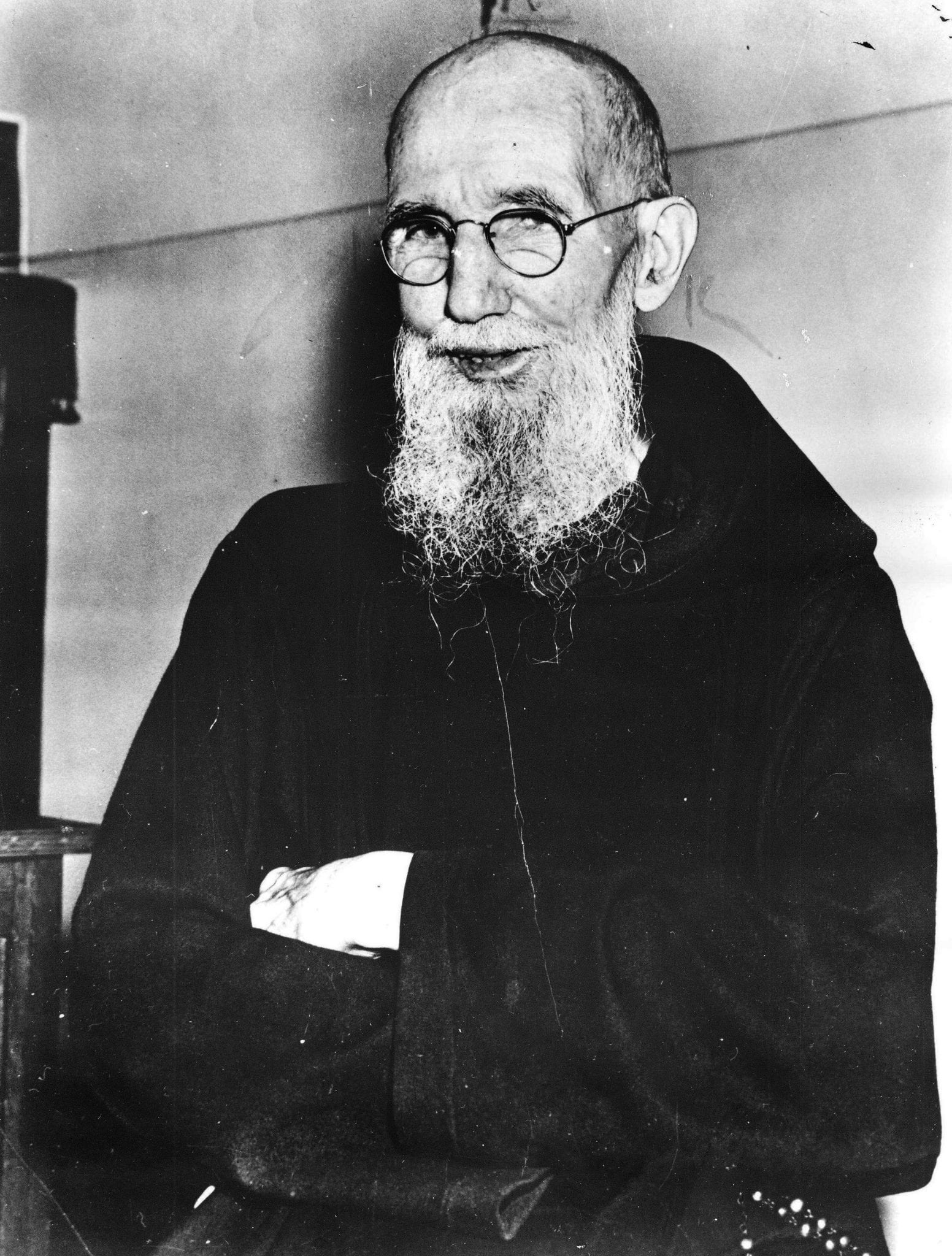

Father Solanus Casey was known as Father Solanus, a member of the Capuchin Franciscan order of priests. He died in 1957.

He was a priest who wasn’t allowed to preach, but instead turned his ears and heart to the needy.

Tens of thousands of people attended the beatification Mass Saturday at a Detroit stadium. Italian Cardinal Angelo Amato read a letter from Pope Francis, who described Casey as a “humble, faithful disciple of Christ.” He was given the title of “blessed.”

Casey is credited with interceding to cure a Panamanian woman of a skin disease while she prayed at his tomb in 2012. She attended the Mass.

Casey can be made a saint in the years ahead if a second miracle is attributed to him. He is only the second U.S.-born man to be beatified by the Catholic Church, joining the Father Stanley Rother, a priest killed in Guatamala’s civil war, who was beatified in Oklahoma in September. One U.S.-born woman is a blessed, and two others have been declared saints.

RELATED: Blessed Rother ‘an authentic light’ for church and world, says cardinal

“It’s a great event,” Archbishop Allen Vigneron, who leads the southeastern Michigan church, said of the honor for Casey. “It’s hard to communicate how vivid and real the presence of Father is to our community.”

Even 60 years after his death, “people don’t say, ‘I’m going to Father’s tomb,'” Vigneron told The Associated Press ahead of the ceremony. “They say, ‘I’m going to talk to Father.'”

Casey, a native of Oak Grove, Wisconsin, joined the Capuchin religious order in Detroit in 1897 and was ordained a priest seven years later. But there were conditions: Because of academic struggles, he was prohibited from giving homilies at Mass and couldn’t hear confessions.

“He accepted it,” said Father Martin Pable, 86, a fellow Capuchin. “He believed whatever God wants, that’s what he would do.”

RELATED: Solanus Casey, the priest who answered the doorbell

He served for 20 years in New York City and nearby Yonkers before the Capuchins transferred him back to the St. Bonaventure Monastery in Detroit in 1924. Wearing a traditional brown hooded robe and sandals, Casey worked as a porter or doorkeeper for the next two decades, but his reputation for holiness far exceeded his modest title.

The unemployed shared their anxieties with Casey, the parents of wayward kids sought his advice, and the ill and addicted asked him to urge God to heal them. As he listened, he took notes that were later turned into typewritten volumes of his work.

Later in life, when Casey was stationed at a seminary in Huntington, Indiana, Detroiters boarded buses for a four-hour ride just to see the man with a wispy white beard. Mail piled up from across the country.

“He had a gentle presence. He left people with a wonderful feeling of peace inside their hearts,” Pable said. “He would say, ‘Let’s just pray about this and see what God wants to do.’ Some people were not healed. He told them to bear their problems with God’s help.”

RELATED: Detroit archbishop says Solanus Casey exemplifies ‘a worker in the field hospital of mercy’

Casey, who died in 1957, also co-founded the Capuchin Soup Kitchen, which serves up to 2,000 meals a day to Detroit’s poor.

The Capuchins built a center that bears his name and explains his life story. The public is invited to pray and leave handwritten pleas atop his tomb. Casey’s name is invoked by many people who attend a weekly service for the sick.

Shirley Wilson, 78, said she regularly prayed to Casey to help her nephew get a kidney. He got one a few weeks ago.

“It was a perfect match,” she said. “I believe in miracles.”

Vigneron hopes Casey will inspire people to show mercy toward others.

“We need to care for the poor and give them a high priority,” the archbishop said. “Father was very loving and understanding to people who came to him with their troubles.”

Crux staff contributed to this report.