JEFFERSON CITY, Missouri — Mozart proclaims the organ to be the “king of instruments,” but it actually works more like a parliament.

It reigns when its panoply of voices speaks in harmony and balance, with whispers and crescendos drawing upon the full spectrum of sound and human emotion.

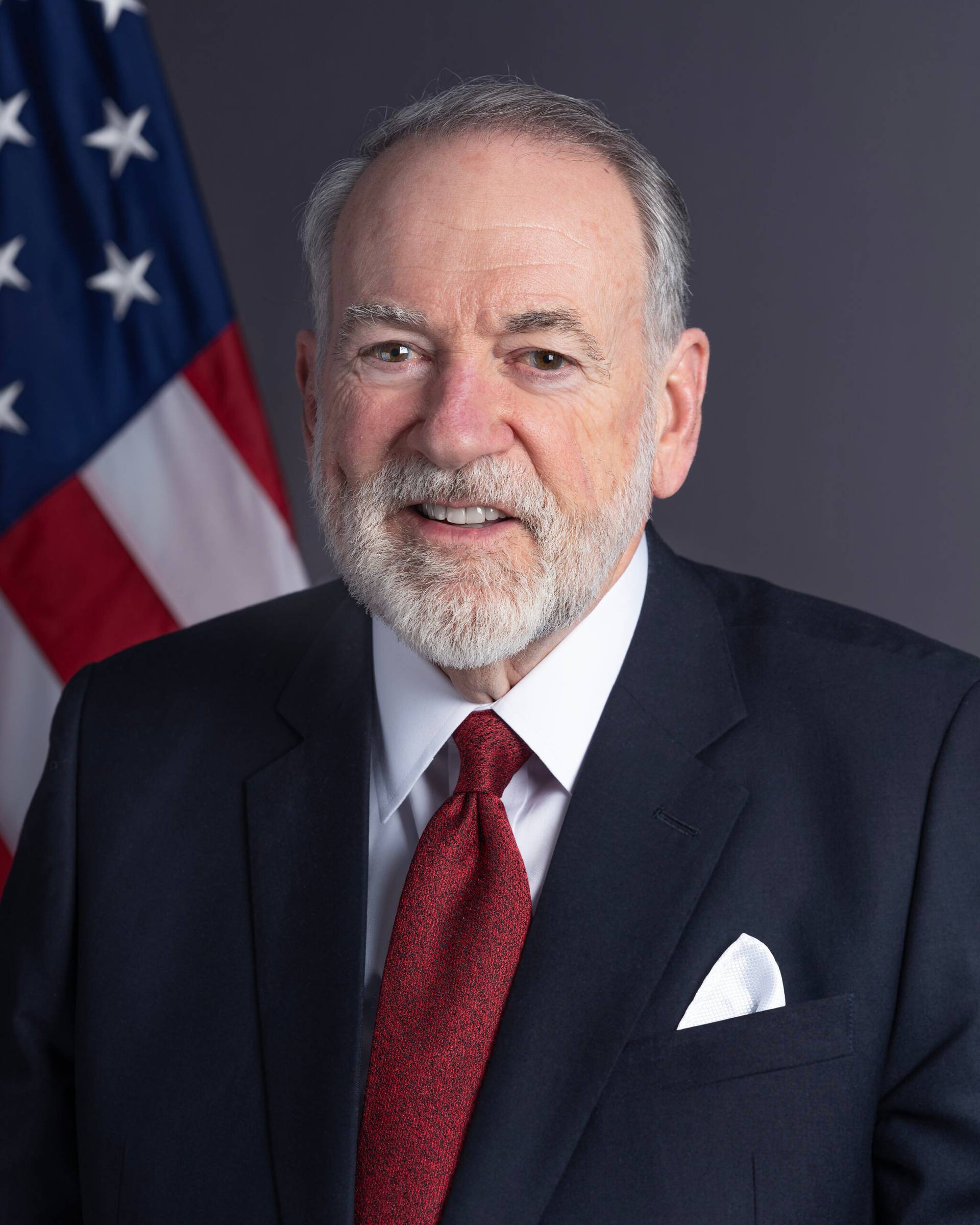

“There’s the capacity to surround and fill the space with a volume and complexity of tone that no other instrument can match,” said Father Jeremy Secrist, pastor of St. Peter Parish in Jefferson City.

This year, Jefferson City Bishop W. Shawn McKnight appointed Secrist to serve as the bishop’s delegate for care and promotion of pipe organs.

The new role includes taking an inventory of existing pipe organs in parishes, advocating for their preservation, restoration and maintenance, and cultivating an appreciation for the contribution they can make to Catholic liturgies.

“What makes them particularly well matched to congregational singing is that, like members of a choir, each of the windblown pipes produces an individually generated sound,” Secrist told The Catholic Missourian, newspaper of the Diocese of Jefferson City.

He called the pipe organ “the oldest stereo instrument — one that is able to fill a space, that is able to support the voices of men, women and children.”

A single properly engineered set of tuned pipes, built with skill and technology acquired over 1,500 years of organ-building, “can support and encourage singing in a way that other instruments simply cannot,” Secrist said.

Organs with three, five, 10, 20, 30 or even 50 sets of pipes offer arrays of variety and volume. Pipes can be made of wood or metal and range in length from a few inches to 8, 16 or even 32 feet.

“It’s not just multiplication of voices or volume, but of color,” he said.

Notes can be held. Harmonies can be accentuated. Voices of varying pitches, timbres and volumes can be mixed, depending on the occasion, the type of music and the people who are singing with it.

“I would liken a pipe organ to the Psalms,” Secrist said. “When you go through all 150 of them — as King David sings and prays and repents and even curses — we find representation of all human emotions. And in all of those, God is able to work.”

The pipe organ is “able to plug into, to enter into the soul, the heart of who we are,” Secrist added.

Organ pipes are arranged into “ranks,” each containing approximately 61 notes of the same voice and placed atop wooden wind chests filled with pressurized air. When the stop knob that controls one of the ranks is activated, the pressing of a key or pedal allows the pressurized air to enter the pipe of the corresponding note. The column of air vibrates inside the pipe, creating a pitch that mixes and harmonizes with the vibrations from neighboring pipes as they are activated.

“The longer the pipe, the lower the pitch,” Secrist explained.

Pipes of different sizes, shapes, materials and wind pressures produce a colorful palate of sounds that can be adjusted by blending the various stops.

Organs started out simple in ancient times and became more complex over the centuries as organ builders discovered innovative ways to construct the pipes and the intricate mechanisms that force air through them.

Mathematicians calculated the effect of thickness, radius, height and degree of tapering on the sound of each pipe. In doing so, they found new expressions of God’s beauty and wisdom reflected in creation and the laws that govern it.

Beginning about 60 years ago, some pipe organs were removed or heavily modified. But in some diocesan parishes, the pipe organ remained an integral part of parish life.

“They don’t think of it as something secondary,” Secrist said. “And now we hope to provide some good direction for maintaining these instruments for future generations.”

Secrist led the Gregorian chant schola at the Pontifical North American College when he was a seminarian in Rome. He maintains memberships in the American Guild of Organists, the Organ Historical Society and other organizations, which allows him to remain in contact with world-renowned composers, musicians, organ builders and teachers.

The priest noted that, through the centuries, music and art have contributed significantly to the well-being of civilization and society.

Just as the Church in its mission of preaching the Gospel has drawn together people of different nationalities, cultures and political situations, “so, too, can music be that kind of a link between people of diverse backgrounds,” he said.

He maintained that music also has the power to reveal love at its deepest level.

“And whom should we love more than anybody else but the Lord? So the music that we use is an expression of that love, of the deepest longings of our heart.”

Nies is editor of The Catholic Missourian, newspaper of the Diocese of Jefferson City.

Crux is dedicated to smart, wired and independent reporting on the Vatican and worldwide Catholic Church. That kind of reporting doesn’t come cheap, and we need your support. You can help Crux by giving a small amount monthly, or with a onetime gift. Please remember, Crux is a for-profit organization, so contributions are not tax-deductible.