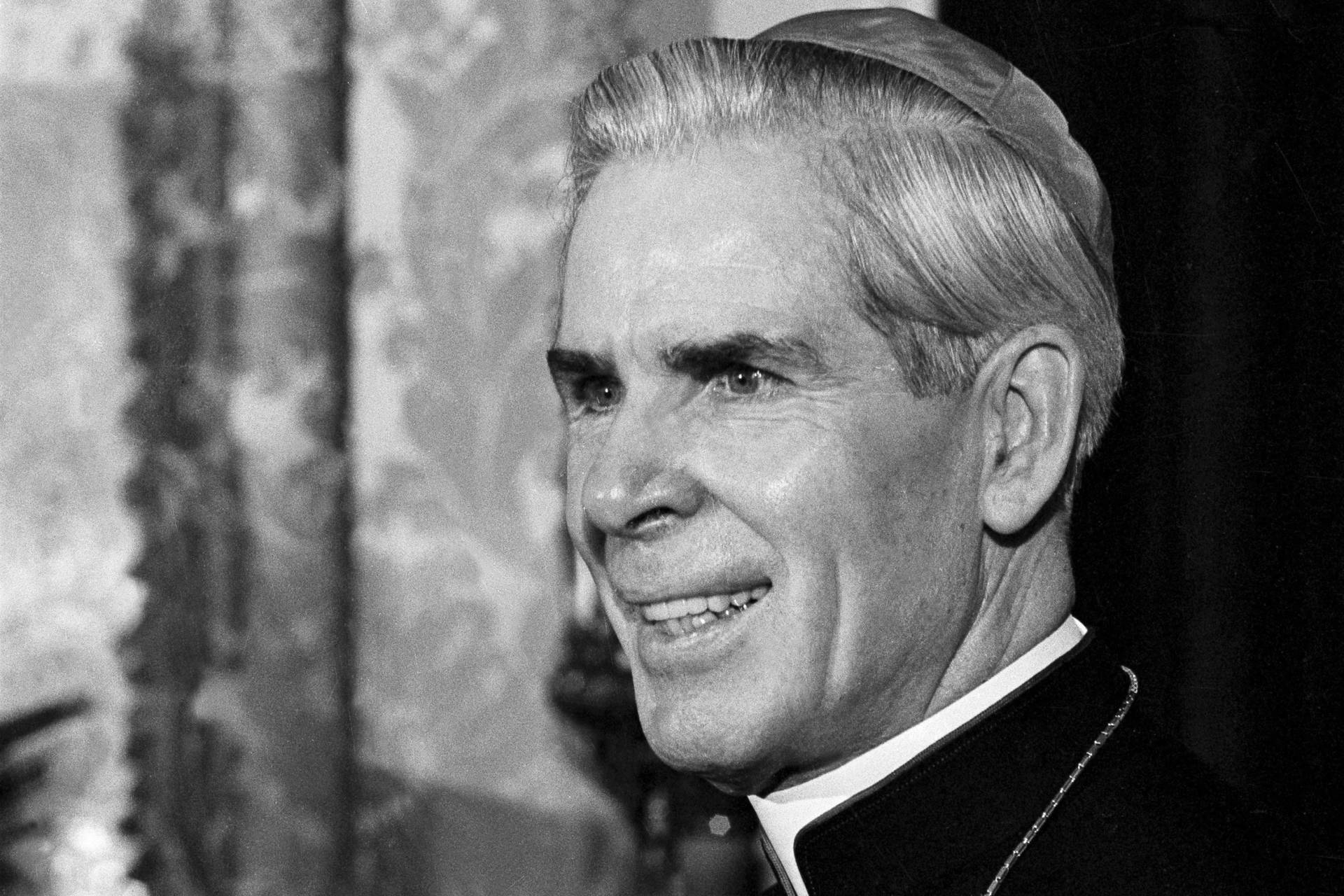

Cardinal Timothy Dolan of New York is a former president of the U.S. bishops’ conference, and at just 64 he’s positioned to be a force in Catholic life, both at home and abroad, for some time to come.

In the second installment of John Allen’s exclusive Crux interview, Dolan discusses what Pope Francis had to say about US airstrikes against ISIS, how the pope can call out moderate Muslim leaders, the Obama administration’s contraception mandates, the 2016 elections, and Communion for pro-choice Catholic politicians, plus the Church’s sexual abuse scandals and what Francis can do to move the ball on reform.

Crux: What did you make of what Pope Francis had to say about US airstrikes in Iraq?

Dolan: I was somewhat surprised, and I was very happy. I was surprised because the perception is that usually the Vatican is suspicious and critical of anything the American government does from a military point of view. I was also surprised because usually a pope stays in the sphere of the ideal when it comes to this.

In a generic way, which is still trying to be parsed, he led one to believe that some kind of military intervention could not only be free from moral criticism, but could even be morally laudable. That’s rather new, and it reminds us of what John Paul II did in the Balkans. Once again you had a man who was being caricatured as this runaway pacifist who all of a sudden said, ‘Wait a minute, there are legitimate uses of military power, and this could be one of them.’ That was a surprise, and I found it a welcome and refreshing surprise.

As an American, it was very good to hear the pope that I love, who leads the Church I would live and die for, also smiling on my country in recognition that it does have a global responsibility and that, if morally used, it can be for the betterment of humanity. I found that a very good moment.

Nobody wants to take pride in a disaster, but in your farewell address as president of the U.S. bishops’ conference in November 2013 you warned that anti-Christian violence around the world was going to get worse. Looking at what’s happening with ISIS in northern Iraq, do you feel vindicated?

I wish I didn’t have to say that, because obviously it’s nauseating to see what’s happening, but yes. I’m grateful for the grace that led me to speak about that, and I’m grateful to the people who helped me do it, yourself included. I’m grateful to the people who have written with such cogency on this matter. I think we’ve turned a corner. Since the Foley beheading, there have been a least a dozen people who usually aren’t very intense in their reactions to this, not all of them believers, who have said to me, ‘Now we know what you’re talking about. Now we know it’s not hyperbole to say that we are dealing with an extremist, irrational, anti-Christian, anti-religious band of thugs that really has a worldwide platform and must be stopped.’ The characteristic they find most repulsive is their particular venom for Christianity.

God can bring good out of evil, and this could become a time when the spotlight of the world falls on something that many of us have been trying to call attention to for years, namely that there is a real epidemic of Christianophobia around the world.

When a Catholic in the pews asks you ‘What can I do?’ about anti-Christian violence, what’s your answer?

First, I wish more Catholics would ask that. Unfortunately, Catholics in the pew here are also Americans, who have a short attention span when it comes to foreign affairs. As hard as we try, it’s still not kitchen table conversation.

Second, I would say that you need to become acquainted with those organizations that are on the front lines of this, such as Aid to the Church in Need, the Catholic Near East Welfare Association, CRS, even the work of the Holy See and the bishops’ conference in trying to bring attention to this.

Third, you need to exercise your right as an American citizen to let your elected representatives know that this is a high concern to you, and that our government has seemed less than sensitive to this matter, and it’s about time it becomes very aggressive in defending the rights of religious minorities.

When you say ‘government,’ are you talking about the Obama administration or is this blind spot across the board?

I’m afraid it’s part of all administrations. I think there have been recent moves by the Obama administration that would lead one to believe this is becoming a front-burner issue. I sure hope it is.

Given how concerned you are, was it disappointing to you that Pope Francis was recently just a few kilometers away from the DMZ between North and South Korea, and didn’t say anything about the suffering of Christians in the north?

I expected that he would say something, but I learned a long time ago to trust the Holy See on things like this. I’m not trying to cover for them, but they are very aware of such complexities that they have to measure every word. If they do or don’t do something, it’s very carefully thought out. So, yes, I hoped he would say something, but the fact that he didn’t wasn’t a disappointment because I assume there are reasons.

You know that even in my role, very often I am asked to speak publicly about matters. I will always consult the bishops’ conference, and I’ll consult the nuncio and ask if he can get some direction. I’ve been asked to write about Ukraine, I’ve been asked to write about China, I’ve been asked to write about Boko Haram … and I ask them to help me identify things I should and shouldn’t say, particular things that might exacerbate an already tense situation. I have found the Holy See to be unfailingly perceptive in telling me what would be good to say, and what wouldn’t be good to say. I trust them there.

Would you say the same thing about China? The pope extended an olive branch to China without mentioning its record on religious freedom.

There I’m influenced by the large Chinese population in New York, with whom I meet often. On that front, I was just grateful for the attention he was giving to China. That’s what I detect from our own people here. The [Chinese] priests, religious, lay leaders, tell me that rather than emphasizing injustices and persecution, it might be more effective to constantly try to show China that the Church’s presence means no intrusion, no harm, no imperialism, and no judgment. We want them to know that you have nothing to fear from the Church. They tell me, and they’re a lot closer to the scene than I’ll ever be, that’s probably the best approach to China, and that’s the one Francis took.

With Francis, the key point is that charity trumps everything. We lead with charity, and that’s what he’s doing. He’s also got a tough side, and I’m glad to see it, but charity comes first. You can characterize different popes as leading with different virtues. For Pius XII, for instance, the virtue was prudence, and he’s both criticized and praised for it. With Francis, it’s peace, mercy and understanding; in a word, charity.

[Francis] is very humble when you’re with him personally in admitting that there are certain areas of the world he needs tutoring on … including, by the way, the United States. I find that encouraging, because it’s obvious he wants to learn. He said to [Archbishop Joseph] Kurtz and me, ‘Help me understand the United States,’ down to something as practical as, ‘Where is Louisville?’ Those are very refreshing questions.

John Paul II was very astute when it came to geopolitical things. I think Francis has said, ‘My astuteness is in the gospel, in pastoral life, but I also know I have to grow in my knowledge of this terrain, please help me do that.’

If the pope asked you for one concrete thing he could do to help put the issue of anti-Christian persecution on the map, what would you tell him?

I would ask him to be more direct in calling for a thoughtful, moderate, temperate Islamic response. We all talk about it, we all believe in our hearts that these fanatics no more represent mainstream classical Islam than the IRA represented Catholicism. But when the IRA blew things up in Ireland, the bishops would immediately say, ‘They’re not Catholics.’ When Islamic extremists act, we don’t hear the thoughtful, moderate, classical Islamic voices, who we all believe are representative of true Islam, speak up in an effective way.

Francis is now the major convener of religious leaders throughout the world, and he did it brilliantly in the Holy Land. I would say, ‘Holy Father, continue your insistence that temperate Islamic leaders speak up, give them a platform to do it, and call them to task. Ask them, ‘Where are you? Because we need you.’

Let’s work with [Archbishop] Ignatius Kaigama in Jos [Nigeria], because he needs us. He’s speaking out. He’s the one who says, ‘Don’t band Boko Haram as Islamic extremists, because they’re butchering Muslims, too.’ Support bishops like that who are in tough spots.’

On another front, Archbishop [Joseph] Kurtz [president of the U.S. bishops’ conference] has called the latest revisions to the regulations for the Obama administration’s contraception mandates disappointing. Do you share that view?

Yes, I’ve spoken to Archbishop Kurtz about this. At first glance, it does not seem to indicate any substantive changes. We do want to study it closely, but he says he doubts there’s something in it we can live with, and I share that assessment.

Some people would say that in light of Francis’ statement that the Church doesn’t need to be talking about abortion and contraception all the time, this fight isn’t worth the time and treasure the American bishops are investing. Why do you think it’s worth it?

I would hope that Pope Francis would find the strategy of the American bishops to be very much in line with his priorities, in so far as what we’re doing is speaking out on behalf of the most fair, comprehensive, and life-affirming health care possible that can be delivered to the most people. We’re on the side, and have been since 1919, of more extended, affordable, and just health care, which is a very controversial American cause.

What people sometimes forget is that your beef with Obamacare wasn’t just the contraception mandates, correct? It’s also that it didn’t go far enough in terms of the number of people covered.

I can tell you that I’ve treasured my conversations with President Obama, and I’ve found him unfailingly courteous and open. On one occasion, the candor of our conversation led him to say, ‘I still can’t understand why you bishops opposed our first health care package.’ I said, ‘Mr. President, let me tell you why. We didn’t think it went far enough. You told us that you wanted health care to be comprehensive, but your proposal left out the baby in the womb and the undocumented immigrant. That’s not comprehensive. We want all those people covered.’ In some ways, we’re arguing with the president that this is not as comprehensive and as life-affirming as it should be.

The more recent arguments we’ve had with them have been on religious freedom, but even there we’re willing to say, ‘Look, you want to provide these services, such as abortifacients and contraceptives? That’s your call. Go ahead. We’ll bristle, we think it’s ill-advised, we think in the long run it could be counter-productive for the Republic, but go ahead. But please, just don’t make us advocate for them, direct our people to them, approve of them, and subsidize them. That’s all we’re asking. If you respect our religious freedom, we’ll probably be on your side in championing the legislation.’

We would almost turn the argument around [to the administration] and say, ‘Why do you think this is worth fighting for?’

What do you think the answer is?

For those who say to us bishops that we’re culture warriors and ideologically driven on this issue, I would suggest they ask the same about certain people in the administration. Are there certain people who say that ideologically we have to be so aggressive, so unbending about providing things such as abortifacients and contraceptives, that we will allow absolutely no middle road? I hope the president is above all that, but I do think there are people close to him who are saying we must make this a question of ideological purity, and you can’t bend on it.

Mid-term elections are close, and soon the 2016 race will heat up. Where are the American bishops today on the issue of Communion for pro-choice Catholic politicians?

In a way, I like to think it’s an issue that served us well in forcing us to do a serious examination of conscience about how we can best teach our people about their political responsibilities, but by now that inflammatory issue is in the past. I don’t hear too many bishops saying it’s something that we need to debate nationally, or that we have to decide collegially. I think most bishops have said, ‘We trust individual bishops in individual cases.’ Most don’t think it’s something for which we have to go to the mat.

Turning to the sexual abuse scandals, critics say there’s been relatively little forward movement from Pope Francis other than meeting with victims. Are you concerned that people may draw the conclusion that while defending the poor and making peace are priorities for this pope, keeping children safe in the Church isn’t?

I’m afraid some people may conclude that, but it wouldn’t be the pope’s fault. It’s the fault of those who never want to attribute to the Church any progress, reform, or renewal on this issue. I believe that Pope Francis is a uniquely savvy leader, who knows that the major service he can perform is to set a tone. He’s said clearly that this is something that cannot be tolerated, that it must be dealt with vigorously, and I’m here to see that’s done.

He also knows that structurally, 99 percent of the implementation must be done by religious orders and by dioceses. All he can do is set the tone.

Is that really all? Or are there concrete steps he could take?

One thing I think he is moving toward is to make it more expeditious, on behalf of the Holy See, to move when bishops request punitive actions against priests. Although we bishops have sympathy for the workload of the Holy See, we still cringe at the slow pace of even clean-cut cases that need to be dealt with decisively.

A second area where he could help us is with accountability for bishops. Yes, there’s fraternal encouragement, support, and calling to task, and that is being done. But we need some precision on the role of a metropolitan and the role of a conference, some way of putting teeth into what are now more exhortative, fraternal solutions. In terms of the ecclesial system, once you move from a diocese the next stop is the Holy See, and as a bishop I would find it immensely helpful and see it as part of Pope Francis’ long-range plan to flesh out how bishops can hold one another more accountable.

You mentioned the need for a vigorous response. Would you find it helpful if people could see this new anti-abuse commission doing something important?

I would find that a very helpful step in the right direction, partly because that work of setting the right tone still isn’t completely finished.

God knows we bishops in the United States are still trying to get this right, and we probably always will be. But we find it very demoralizing to hear bishops in other parts of the world, even some leaders in Rome, who still feel this is an Anglo-Saxon problem, and who say we’ve capitulated to the demands of the media, that we have violated the rights of our priests, and that this [abuse crisis] is only a version of vitriolic anti-Catholicism. Now, are there elements of anti-Catholicism in it? Yes, but basically this is a question of elementary justice, it’s a question of the protection of our young people, and it doesn’t just concern the Catholic Church in the United States, England, Ireland, and Australia. We still find some of our brother bishops, including some in Rome, who say that we’ve been overly zealous and overly rigorous.

To be honest, we also find it among some of our own people. If you’re talking about editorials in newspapers, most of the time bishops are attacked for not being strict enough. Internally, when I go to parishes, what I hear is, ‘Why did you remove Father So-and-so? It was an injustice, his rights were violated. We want him back.’

Bottom line, Pope Francis has helped me govern better by elevating [the abuse crisis] to a major concern of the universal Church and in letting it be known that he wants to be a crusader here. Anything that could demonstrate that in a more coherent way would be hugely helpful.

In tomorrow’s final installment, Dolan discusses a possible visit by Pope Francis to New York in 2015, the upcoming Synod of Bishops on the family in Rome, some hard questions he faces in New York about parish closings, plus Dolan’s own next act, including whether he’s interested in a job in Rome. [Spoiler alert: Not so much.]