Dorothy Day was the subject on Tuesday night when I spoke at the College of Mount Saint Vincent in Riverdale, New York, in the company of Robert Ellsberg of Orbis Books and Sister Simone Campbell of Network.

The three of us came together under the aegis of the college’s annual Margaret F. Grace lecture, to reflect on the subject of “Dorothy Day and the Solution of Love.”

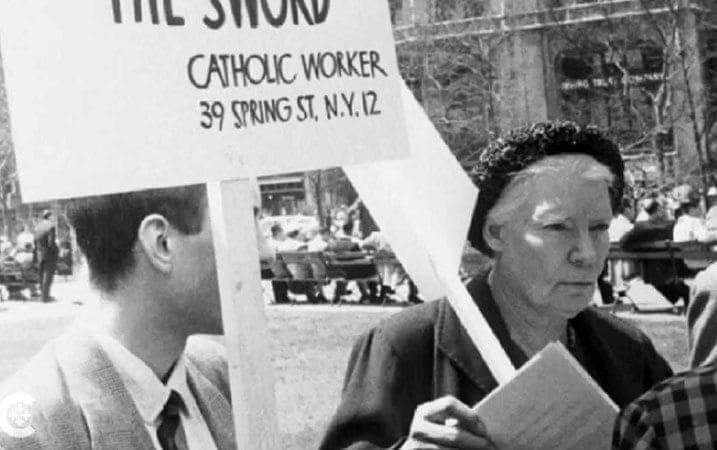

Day, of course, was the co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement, a champion of the Church’s social justice tradition, and one of four great Americans lifted up by Pope Francis during his September 24, 2015, speech to the U.S. Congress. (The others were Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr. and Thomas Merton.)

In essence, my take was that Dorothy Day is the ideal American sainthood candidate in the Francis era, and it would be both symbolically and substantively apt if he can be the pontiff to raise her to the honors of the altar.

First, a stipulation: There are many devotees of Day who are ambivalent at best, and downright opposed at worst, to the whole idea of making her a saint. They worry that some of her prophetic edge might get rubbed off in the process, and also that the money involved could be better spent serving the poor.

I appreciate the objections. It’s a fact that the tab for high-end sainthood causes can run to around $1 million, including travel to collect testimony, paying canon lawyers, putting together the paperwork, and staging both a beatification and a canonization ceremony. I can see why spending such a sum on a personal honor just doesn’t feel very “Catholic Worker-ish.”

On the other hand, saints are quite literally priceless in shaping the Catholic imagination, and there’s a strong case that seeing Day formally canonized would be a boost to the things she stood for well worth the investment.

Here are three reasons why she’s such a perfect fit for Francis.

First she embodies the passion for the poor that’s such a hallmark of Francis’ papacy.

After his election in March 2013, Pope Francis said his dream was of a “poor Church for the poor,” and few Catholic figures have ever lived that dream more thoroughly than Day. She co-founded the Catholic Worker movement along with Peter Maurin in the 1930s, amid the Great Depression, and for the next half-century was one of America’s most prominent voices on behalf of the downtrodden.

“Her social activism, her passion for justice and for the cause of the oppressed, were inspired by the Gospel, her faith, and the example of the saints,” the pontiff said in his speech to Congress, calling her an icon of the dream of “social justice and the rights of persons.”

Francis has made defending victims of a “throw-away” culture a cornerstone of his agenda, and few American Catholics have ever thought more deeply, or spoken more passionately, about the social mechanisms that produce exclusion and marginalization more than Day.

Second, Day is also a compelling example of the integration of the Church’s pro-life teaching and its peace-and-justice positions, another defining characteristic of the Pope Francis approach.

Shortly after his election, Francis famously said he didn’t feel the need to “talk much” about issues such as abortion and gay marriage, because the Church’s positions are already well known. In some quarters, the remark bred suspicion that Francis might be throwing in the towel on the Gospel of Life.

We now know that’s not the case. In his recent exhortation Amoris Laetitia, for instance, here’s his language on abortion: “If the family is the sanctuary of life … it is a horrendous contradiction when it becomes a place where life is rejected and destroyed … no alleged right to one’s own body can justify a decision to terminate that life.”

Rooted in her own experience of having had an abortion and later seeking forgiveness, that’s a view Day likely would echo – though, like Francis, without being drawn into what would later become known as America’s “wars of culture.”

Hers was a quieter way of being pro-life, putting the emphasis on compassion and mercy, another trait she shares with the “Pope of Mercy.”

Fundamentally, what links Day and Francis is an expansive view of what counts as a “pro-life” cause, reaching out to include not only the unborn but also migrants and refugees, exploited workers, death row inmates, even the planet itself. The idea is that life must be protected at all stages, and against whatever menaces it.

Finally, Day would be a perfect American saint for Francis because she was a living illustration of a point he’s struggled to make time and again, admittedly with mixed success: To promote leadership by women in Catholicism, you don’t have to make them priests, you just have to get out of their way.

Quite obviously, Day would finish on any short list of the most influential American Catholics of the last century. Her impact, and her legacy, tower over most of the ordained clergy who served during the span of her lifetime.

Day once quipped that she opposed female priests because if women were ordained, fewer men would attend the liturgy, and there are few enough already! Fundamentally, her focus wasn’t on inside Church baseball – she wanted to get on with trying to change the world.

In that sense, and allowing for the obvious differences among them, Day is akin to, say, Mother Teresa, and even Mother Angelica. In their unique fashion, all three proved that the lack of a Roman collar is hardly an impediment to leaving a mark on the Church.

Day was formally declared a “Servant of God” in 2000, and her sainthood cause was endorsed by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in 2012. There’s a guild in New York supporting her candidacy, although there’s no clear sense yet of if, and when, a beatification might occur.

These procedures take time, although Francis has demonstrated a penchant for fast-tracking things when he’s of a mind to do so. (The technical term for that is an “equipollent” canonization, in which a pope sets aside many of the formal requirements.)

If he were looking around for a current American cause under which he might want to light a fire, it’s hard to imagine Dorothy Day wouldn’t seem an awfully attractive possibility.