The headline for the release of Amoris Laetitia could well read something like: “World Shocked, Pope Still Catholic!”

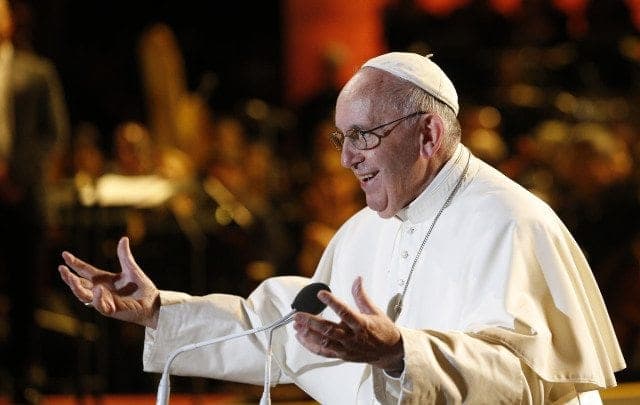

In what will come as little surprise to anyone who pays attention to the Catholic Church, but may startle those accustomed to thinking of Pope Francis as a break-the-mold sort of leader, the pontiff rejects gay marriage, gender theory, in-vitro fertilization, and birth control in this new document.

On the other hand, one could create a headline praising the pope as a progressive for saying that the women’s movement can be “a call of the Spirit,” or for his long quotation from Martin Luther King on the nature of Love.

The truth is that those looking to love this document will love it, and they will find their reasons why. Those who presume to criticize the Holy Father will also find their reasons within the document to do so.

Between those two headlines, however, there is another: “No One Surprised, Pope Still a Jesuit.”

In speaking to members of the Society of Jesus, Francis often has used the language of “we Jesuits.” He still very clearly finds his spiritual home in the Society of Jesus, and that is abundantly clear in Amoris Laetitia.

Throughout the exhortation, His Holiness displays a distinctive Jesuit spirituality rooted in the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius. Precisely because this spirituality holds dear both individual discernment and the basic understanding that God works with each human person individually in the context of the wider Church, it is capable of holding both of the aforementioned approaches to this particular exhortation in a dynamic and creative tension.

When one reads Amoris Laetitia, one finds many clues which point to the essential role of the experience of the retreat of Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola, which he would have made twice in his Jesuit formation, in shaping Francis’ own theological vision.

One comes when Francis speaks about the importance of the “hidden life of Jesus,” the period of time between the narratives of the birth of Jesus and his public ministry as important to understanding the family. There is nothing at all about this time period in scripture, and so we understand it only by contemplating what it must have been like. Such a contemplation is one of the more noteworthy ones in the Exercises.

There are also more obvious places in the document where the Spiritual Exercises shine through, as they do in the emphasis that we are all sinners loved by God. This is one of the graces that all who make the Exercises pray for during the first part of the retreat.

If those aren’t obvious signposts enough, though, Francis directly quotes St. Ignatius in one of the most famous phrases of the Spiritual Exercises in emphasizing that “Love is shown more in deeds than in words.”

What becomes clear, then, is that the lens of Jesuit spirituality is one which helps to bring Amoris Laetitia into sharper focus. It is understatement to say that volumes could, and have, been written on this spirituality, and so focusing briefly on one aspect helps to clarify the rest.

“Discernment” is a word which appears often in Amoris Laetitia, and its proper exercise is a key principle in Jesuit Spirituality.

St. Ignatius, in his convalescence after having been wounded at the battle of Pamplona in 1520, found himself reading the life of Christ and the lives of the Saints. He notices that when he thought of returning to his former life, he was left dry and arid, but when he thought about doing what St. Francis of Assisi and What St. Dominic did, he was filled with a feeling of peace.

Slowly, but surely Ignatius came to understand that that feeling of peace was God calling to him, guiding him sometimes like a teacher guides a pupil, and later on guiding him as one friend guides another. He came to call this feeling consolation, a sign of God’s presence inviting him along the way.

Ignatius was also aware of what he calls “the enemy of our human nature,” a force which guided him, and all of us, away from peace and true joy. Those moments he calls desolation, from the Latin which means “to be left alone”.

Thus, stated in an overly simple manner, we try to move towards real consolation, and away from those things which leave us sterile and alone. In doing so we trust that God is moving in the very feelings which he created in us, precisely so he could communicate with us.

It is little surprise, then, that Francis seeks to provide us with a path to just such consolation in family life in Amoris Laetitia, rather than focusing on the desolate experience of divorce.

None of this is done in a vacuum, however. While there is a robust vision of discernment which affirms prior Church teaching on conscience, which is upheld by both Benedict XVI and St. John Paul II, there is also a clear understanding in Amoris Laetitia that all of this discernment is done in the context of the Church as a whole. Francis calls the Church itself a “family of families.”

So while there is a respect for the individual’s experience of God, there is an understanding that in all of this we need, to borrow a line from the Spiritual Exercises, “Sentir con la Iglesia,” which is to say, think and feel with the Church.

This thinking and feeling is the other guiding principle that underpins the exhortation. It is a sense that as we discern, we have a particular relationship of love to each other which should inform how it is that we come to ultimately choose the paths that we take. The sum of those relationships requires that our consciences be formed by the magisterium without, as Pope Francis notes, having our consciences replaced by it.

A helpful lens through which we can understand Amoris Laetitia is clearly the lens through which the man who wrote it himself relates to God. When we can understand it in that light, we might better understand the nuance of a document which, despite its length, admittedly still leaves many things unsaid.

Father Michael Rogers, SJ, is a Fellow at the McFarland Center for Religion Ethics and Culture at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester MA.