There are certain Biblical stories that have been accepted and absorbed into popular culture. Even if someone knows nothing else about the Bible, or is completely disinterested in all things Biblical, these stories still find a warm reception.

Of these many stories, the parable of the Prodigal Son stands out. Even the most distracted or religiously indifferent of persons knows the story and is encouraged by it.

While the story is clearly about mercy and compassion, there is another lesson. The story has a blatant and strong refutation of self-righteousness. The parable stands as an accusation against anyone who forgets their own falleness and need for forgiveness and acceptance.

Admittedly, the story’s denunciation is discreet. It could be easily overlooked by many, especially those who are guilty and blinded by their own self-righteousness.

Let’s look at the story. We know the account: a man has two sons, one asks for his inheritance early, receives it and lives a life of dissipation. In time, a famine takes his livelihood away. He is destitute and working in a pigpen. In his sorrow, he undergoes a conversion and realizes that his father’s servants are better treated then he is in his current state.

He resolves to return home and beg for his father’s mercy, that his father might at least allow him to be one of his servants. Meanwhile, the other son has remained dutiful and worked hard on his father’s estate.

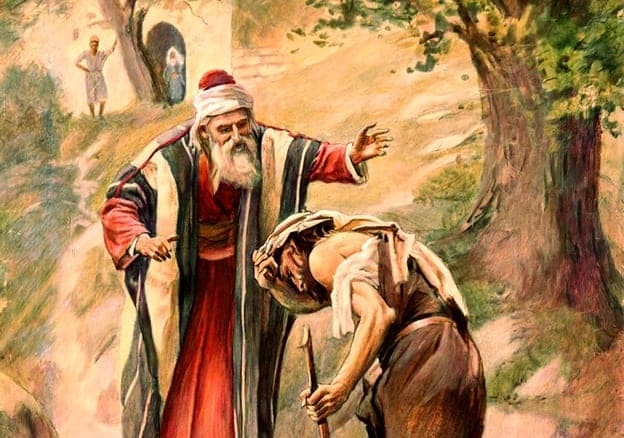

As the younger brother is returning home, his father sees him and runs to him, rejoices over his return, and orders a large celebration.

Commenting on this scene, Pope Francis observes: “Yet when he is at his lowest, he misses the warmth of the father’s house and he goes back. And the father? Had he forgotten the son? No, never. He is there, he sees the son from afar; he was waiting for him every hour of every day. The son was always in his father’s heart, even though he had left him, even though he had squandered his whole inheritance, his freedom.”

In the meantime, as the older son returns from work, he hears and sees the party. He doesn’t understand and is told by a servant about his brother’s return. He is upset and refuses to enter the party.

The older brother’s physical location represents his spiritual state: he’s outside, alone, and in the dark. The notorious sinner, his brother, is inside, with family and light, celebrating his father’s mercy and his readmission into his family.

When the father hears of the older son’s refusal to come into the celebration, he goes to his son. After an initial exchange, the father’s words ring out: “My son, you are here with me always; everything I have is yours. But now we must celebrate and rejoice, because your brother was dead and has come to life again; he was lost and has been found.”

The father’s words are humbling to the older brother (and to many of us). They are a summons to get out of ourselves, our hurt, our entitlement, and our resentment. The words are an invitation to freedom, compassionate love, and joy. The older brother is so wounded by his supposed slight that he cannot see and rejoice over the obvious: his brother was lost, away from family, and in a dark place. He has returned home!

As his sibling, the older brother should celebrate that his brother has returned home. He should join his father and his household in the delight of the moment.

The invitation stands. Oddly, we are given no conclusion to the parable. The story ends with the father’s sobering words. We never hear whether the older son humbles himself and enters the party or whether he remains obstinate? Does anger, resentment, and entitlement win?

While we may not know the conclusion of the parable for the older brother, we do have the power to decide what will happen in our lives. Will darker spirits prevail?

Like the older brother, we all struggle with moments of self-pity and jealousy. We can also wrestle with rash judgment towards another (even a sibling) and with bitterness and indignation towards a family member or neighbor. We can refuse mercy and be enraged by the mercy that some will give to others.

Or we can decide otherwise. We can rejoice over the repentance and rehabilitation of others. We can humble our pride and give a second chance to those around us. We can abandon the darkness around us, enter the light, and enjoy the party.

The choice is ours. What will we decide?