ROME – With the elderly representing the largest demographic cohort of lives claimed by the coronavirus, the Vatican’s top official on life issues has warned against selective care practices that prioritize young patients.

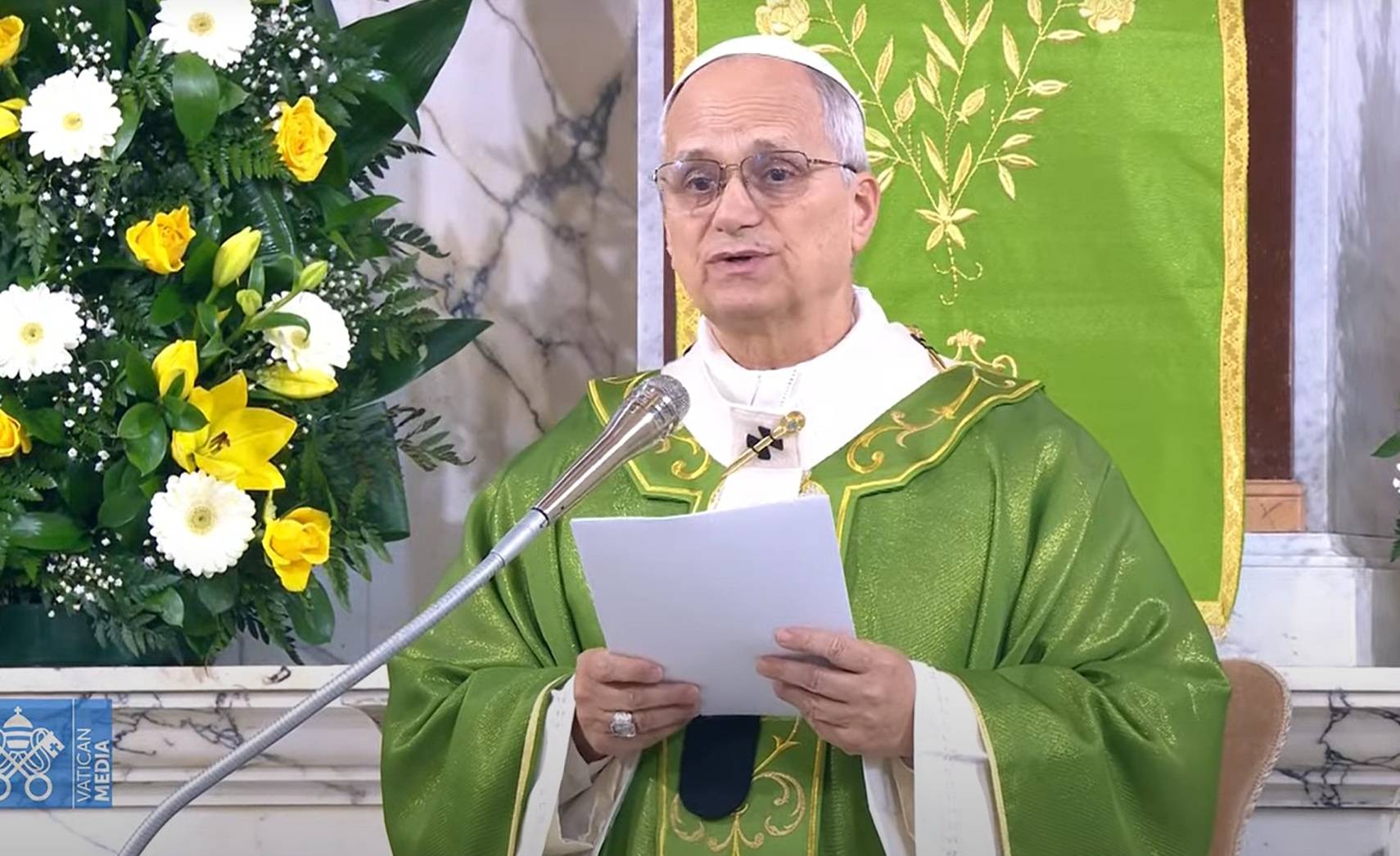

Archbishop Vincenzo Paglia, President of the Pontifical Academy for Life, in an interview with Crux noted that with many hospitals facing shortages of essential equipment such as ventilators at times give preference to patients with better perceived odds of survival, which generally disadvantages the elderly.

“This is the ‘throwaway culture’ in action, forcefully condemned by Pope Francis. [It’s] ‘justified’ by the lack of medical instruments, in turn due to healthcare policy choices that cut costs,” Paglia said, calling the decision to base healthcare and educational funding on cost-saving measures “wrong and misleading.”

He also noted this is happening at the same time courts in Italy, which still leads the world in deaths due to the virus, are debating a possible liberalization of the country’s euthanasia law.

Euthanasia itself is not permitted in Italian law, but in 2017 lawmakers passed a bill allowing adults, together with their doctors, to determine their own end-of-life care, including the terms under which they are able to refuse treatment. The law also allows citizens to write living wills and to refuse medical treatment, artificial nutrition and hydration.

In September 2019, courts ruled it is not always a crime to assist someone in “intolerable pain” to kill themselves. The case involved music producer Fabiano Antoniani, who became tetraplegic and blind after a 2014 car accident and three years later was driven by a member of Italy’s Radical Party to Switzerland, where he underwent assisted suicide.

Initially prosecutors attempted to charge the man who assisted Antoniani with instigating or assisting suicide. The ruling has caused concern among some that it may pave the way for broader acceptance of euthanasia.

“It would be truly incredible that after the pandemic which has put everyone on their knees, if we lowered ourselves further helping the ‘dirty work of death’ even with laws passed by Parliament,” Paglia said.

“No one should ever be abandoned, this is a non-negotiable principle and it must be applied through a cultural response, rediscovering how to care for one another,” he said.

Paglia also spoke of the need to better care for the elderly in normal circumstances, and the Italian government’s decision to allow children to leave the house for brief walks with a parent after receiving complaints that pets could be walked and people could buy cigarettes, but children could not go out.

Below are excerpts of Crux’s interview with Paglia.

Crux: The current pandemic, which is most deadly to the elderly and those with other conditions, comes while the Italian parliament is working to pass a bill to legalize euthanasia, which is also often applied to the elderly. In your opinion, is there a danger of falling increasingly into the mentality of the “throwaway culture,” which tends to consider the elderly as disposable?

Paglia: It is delusional to place age as the only and decisive criterion for care, for salvation or condemnation, which, obviously, relegates the elderly to being too many. Can the weak and elderly be ‘discarded?’

The lack of medical instruments forces choices and do younger people and those with greater hope of recovery receive assistance first? This is the “throwaway culture” in action, forcefully condemned by Pope Francis. [It’s] “justified” by the lack of medical instruments, in turn due to healthcare policy choices that cut costs. But on healthcare and education it is wrong and misleading to try to save. Does the Italian Parliament have to legislate the so-called ‘assisted suicide?’

I hope they will take their example from what is happening. It would be truly incredible that after the pandemic which has put everyone on their knees, if we lowered ourselves further helping the ‘dirty work of death’ even with laws passed by Parliament.

No one should ever be abandoned, this is a non-negotiable principle and it must be applied through a cultural response, rediscovering how to care for one another. The life of each person is my life. At the same time the fight against pain must also be undertaken at all levels, knowing that we cannot prevent death. But certainly we must not cause it!

For the Church and for the Academy for Life in particular, the medical and cultural response to ‘assisted suicide’ and to the ‘throwaway culture’ in terms of healthcare is the diffusion and implementation of palliative care: We all can, and must, take care of each other.

In Rio de Janeiro in 2013, Pope Francis said that he wanted World Youth Day to be rethought as young people in solidarity with the elderly. Given the current pandemic, do you think that it is perhaps a good time to revisit this proposal?

I would first like to speak about the elderly. Or better: of the institutions for the elderly, our ‘rest homes’ – which are anything but ‘restful.’ Today a contradiction has emerged with this model of intervention: they have become places of death, of greater spreading of the virus, and not places of life and care. It is the system that must be rethought in order to bring about the gradual disappearance of these places. The society of tomorrow must be rethought, setting up places of coexistence among the elderly, co-housing, small family homes, or making sure they can stay in their own homes. And the centrality of intergenerational bonds for the life of society must be rethought.

The pope’s proposal fits very well in this horizon. Solidarity between generations is a proposal that goes in the direction of social cohesion. And here the relationship between young people and elderly finds its place.

I hope that the pandemic will find us wiser. I see signs in this regard if I think about the dedication of young doctors and volunteers to the elderly. It’s a small light for the future of society.

The Italian government recently allowed parents to take their children out for a walk, one at a time and near their homes, after hearing complaints from parents. Before, it was not possible. In your opinion, what does it say that during the quarantine, adults could leave to buy groceries, cigarettes, newspapers and other essential items, and pets could be walked, but children were only allowed out after parents complained? Would you say this is a culture of life, or has the value of children been forgotten?

There is no doubt that the whole of society, beginning with adults, is understanding the relationship with children in a new way. In recent times, the frenzy of a hyper-technological society has pushed us to leave our children at the mercy of technological instruments, a sort of electronic babysitter! Now that we are obligated to be at home, we are rediscovering – we hope – the strength of human bonds.

Perhaps a society where fathers and mothers have ‘evaporated’, today is now forced to rediscover fatherhood and motherhood. And therefore remove children from that ‘orphanage’ in which we have pushed them.

It seems wise to me that children are not deprived of the opportunity to leave the house, to see beyond the four walls and beyond the iPad. And the emptiness of the streets can be explained. I think they will learn a lot if we are able to explain what’s going on. And why it happened.

Thinking of the most vulnerable, what can ‘healthy’ people, including Catholics, who are not at risk, do to think less about how the situation is impacting them, and offer something to the poorest and most vulnerable?

The pandemic makes us rediscover that we are all fragile. Not one of us is truly healthy. We need each other. Illness affects everyone and must push us to look both to heaven and to our neighbor. Fragility unites us with the obligation of helping one another. The Gospel puts mutual care into a higher gear: it pushes us to a privileged love for the weakest, the poorest, the most abandoned.

Christians therefore have a twofold task. The first is that of intercessory prayer to free us from evil. The other task is that of helping the poor. Benedict XVI said: the Christian is a heart that sees and is moved.

Follow Elise Ann Allen on Twitter: @eliseannallen