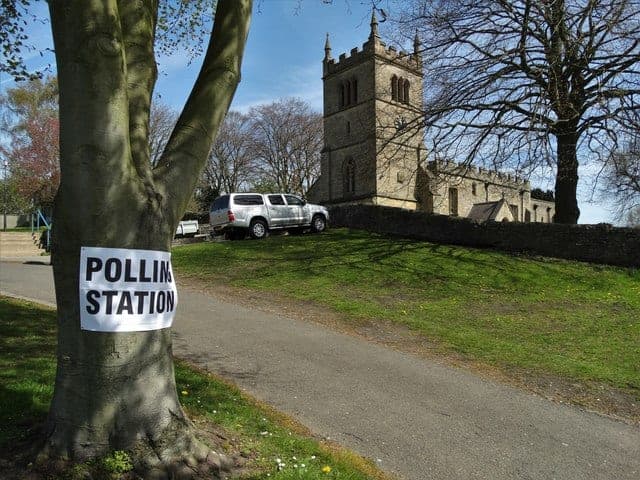

Three things at least have stayed the same in the pastoral letter issued by the Catholic bishops of England and Wales in advance of the United Kingdom’s general election on June 8.

One is a reminder that all those with the right to vote should do so.

Another is a careful blend of what might be called social issues with life issues. And there is the usual plea for Catholics to check that candidates will stand up for their mostly state-funded schools which serve over 845,000 children.

But the letter, to be read in parishes in England and Wales this weekend, contains two novel features which make it more interesting than the usual fare.

The first is an attempt to draw from a paragraph of Pope Francis’s apostolic exhortation, Evangelii Gaudium, a series of general principles to guide the thinking of Catholic voters as they weigh up which party to vote for. The bishops quote its paragraph 183:

“An authentic faith … always involves a deep desire to change the world, to transmit values, to leave this earth somehow better than we found it. We love this magnificent planet on which God has put us, and we love the human family which dwells here, with all its tragedies and struggles, its hopes and aspirations, its strengths and weaknesses. The earth is our common home and all of us are brothers and sisters.”

The bishops deduce from this paragraph the obligation to name and face injustices, the need to protect and nurture the human family as the primary vehicle of mercy and compassion, the need to care about people far away as well as the environment, and the importance of valuing every person as a child of God.

The other ‘new thing’ in the bishops’ letter is Europe, and specifically Britain’s leaving of it.

The four broad Evangelii Gaudium principles, say the bishops, “impact directly” on the election, which takes place at what they call “a pivotal moment in the life of our nations as we prepare to leave the European Union.”

Although individually and privately they were almost all strongly in favor of remaining in a reformed EU, the bishops were studiously neutral in their public pronouncements on last year’s referendum.

In their election letter this week they venture no view on Brexit, but their concern is clear. The outcome of the election, they say, will determine both the approach to Brexit and the decisions about what kind of nation the UK wants to be afterwards.

Although none of the parties is offering to reject the referendum, a gap has opened up in British politics between a “hard Brexit” — in which Britain fails to secure a good deal from the EU, but embraces a free-trade future on World Trade Organization rules — and a “soft Brexit,” in which the UK seeks to retain as much cooperation and involvement with the EU as possible.

In a sense, the two versions of Brexit are not really about trade at all, but reflect a deeper existential choice.

The bishops are clearly concerned about the consequences of a hard Brexit, noting that the election will shape “the priorities we pursue and the values we wish to treasure as our own in the UK and as partners with countries around the world.”

It will also determine, they say, “how we can heal divisions within our society, care for the vulnerable, how our public services can run and whether we can remain a united kingdom.”

The implication is that dropping (or “crashing” in hard-Brexit-speak) out of the EU is a kind of existential moment for the UK, a fork-in-the-road opportunity to face up to who we are and what we stand for.

Will we want to hold onto social gains and protections that came with the EU, or will we opt for a sauve-qui-peut neo-liberal market capitalism that turns its back on all that as euro-socialism?

On the European issue, they have two specific concerns. The first is the status of EU citizens living in the UK and UK citizens living in the EU, who currently face an uncertain future. The issue is scheduled for the early part of the negotiations between London and Brussels.

The second concerns the terms of the new trade deals to be negotiated.

“It is important that in them human and workers’ rights, the environment, and the development of the world’s poorest countries are taken into account,” the bishops say.

The bishops have spotted the real danger of Brexit. It’s not just that the EU departure threatens to reduce jobs, living standards and incomes (which has already started) but that it will lead to the jettisoning of social welfare and rights in the rush to compete with our former European partners.

They also scent a new isolationism in the air, a stand-alone-and-proud mindset that it all too easily fed by the Protestant myth of nationhood, bolstered by Empire-era superiority.

Hence the bishops’ list of what one might call call “global-solidarity” concerns: Keeping the UK borders open and resettling our fair share of Syrian refugees; defending the rights of religious minorities abroad; helping the world’s poorest; and combatting modern slavery.

Naturally they reiterate their longstanding concerns about family, marriage, assisted suicide and conditions in prisons, but I cannot recall a bishops’ election letter so determined to keep Britain engaged with international concerns.

The Church of England leaders struck a similar note in their election letter last week. The Archbishops of York and Canterbury, too, said the election takes place “against the backdrop of deep and profound questions of identity,” and offers a rare opportunity “to renew and reimagine our shared values as a country and a United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.”

They, too, warned that our future trading agreements need to reflect those values and called for the UK “to be an outward looking and generous country, with distinctive contributions to peace-building, development, the environment and welcoming the stranger in need.”

Yet there was a slight difference between the two Churches on what might be called the ‘national question.’

Although neither the Catholic nor the Anglican bishops explicitly call for the Kingdom to remain united, the Anglicans’ language clearly suggests they believe this is desirable, while the Catholics are neutral, stressing only that the election outcome will in part depend on the question of whether the nations of the UK can stay together.

Although there is little appetite for secession in Wales, which voted to leave the EU, both Scotland and northern Ireland voted overwhelmingly to remain, making both Scottish independence and a united Ireland (a long standing dream for nationalist Catholics) far more likely.

Conscious that Catholics are divided on that issue, Scotland’s bishops were staying quiet on both Brexit and the referendum question in their election letter, also to be read out this weekend in the nation’s 500 parishes.

They have stuck instead to a conventional tick-off list of life issues, marriage and family, poverty, asylum, and religious freedom, while urging Catholic voters to “remind our politicians that abortion, assisted suicide and euthanasia are always morally unacceptable.”

But south of the border, Catholics in England and Wales will this weekend be pondering how to apply the bishops’ concerns about the Brexit process to the electoral choice they must make in just a few weeks. It is not easy. Everyone knows the Conservatives will win; the question is how big will be its landslide.

The moment may be pivotal, and the stakes high. Catholics are obliged to vote, and must weigh their consciences. The bishops’ concerns are clear. What is much less clear is how Catholics can bring them to bear on this most unusual of elections.

But if that seems hard, consider the Diocese of Portsmouth in the south of England, whose conservative bishop likes occasionally to take up positions at odds with that of the bishops’ conference of England and Wales.

Last Sunday, Bishop Philip Egan’s own election pastoral was read out in the parishes of Portsmouth, complete with his own top ten issues. There was no mention of Europe or Brexit, or migration and asylum, and no reference to Pope Francis.

Instead voters were invited to ask candidates questions like, “How will they strengthen Britain’s Christian patrimony, its history, classics and values, whilst curbing fundamentalism in its various forms, scientific and religious, and promoting a fruitful dialogue between faith and reason?”

At least at election rallies it will be easy to spot the Portsmouth Catholic voter.