ROME – When most people think of Rome they picture the majestic Colosseum or the countless churches and basilicas sprawled across the city, but deep underground there is another Eternal City that tells the tale of the first pioneers of the Christian faith.

The Catacombs of Domitilla, a vast web of tunnels and tombs used by early Christians for refuge and burial, is finding new life under the muck and mold thanks to restorations sponsored by the Pontifical Commission for Sacred Art, which completed its work May 29 and will open the painted crypts to the public next month.

The catacombs “represent the concrete and legible testimony of ‘Christian death,’ seen by our early brothers as a provisory death in anticipation of the final Resurrection,” said Fabrizio Visconti, superintendent at the Commission, at the unveiling May 30.

The United States is usually called the home of pioneers, from its Westward expansion to its race to the Moon, but Italians also have an extraordinary lineup of explorers such as Marco Polo, Amerigo Vespucci, and Christopher Columbus.

Less than a year after Columbus made his voyage to the New World, Antonio Bosio, a Maltese archeologist obsessed with early Christian history, began his exploration of an old World buried under the city of Rome.

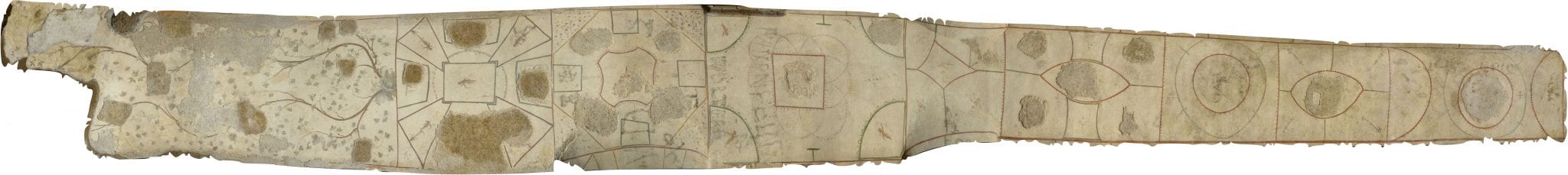

In 1593 Bosio first entered the Catacombs of Domitilla, under the patronage of the Order of Malta, earning the title of the “Christopher Columbus of Rome’s underground.” Like Columbus, Bosio got lost and resorted to the mythological trick of using a ball of thread to trace his steps in the dark labyrinth.

The Catacombs extended for more than 7.4 miles, with two and sometimes four underground floors with a total of 26,250 tombs. The “city under the city” first started with the Ancient Roman tombs of the first century B.C. that multiplied during the second and third centuries after Christ, when it became a popular Christian burial ground.

The origin of the name “Domitilla” is disputed, since there are two plausible options. Flavius Clement, a member of the Flavian royal family and consul under emperor Domitian, was executed for being a Christian in the year A.D. 96 while his wife Domitilla was exiled for the same reason to the island of Ventotene.

But Flavius also had a niece called Domitilla, who, like her eponymous aunt, was exiled to the island of Ponza for her faith. Regardless of which Domitilla gave her name to the plot of land, it became in time the largest catacomb in Rome.

What contributed to the expansion of the tombs was the fact that early Christian martyrs Nereus and Achilleus, two Roman soldiers who converted to the Christian faith and laid down their weapons and lives for Christ, were buried within the complex.

It was also believed that St. Petronilla, the daughter of St. Peter according to late Medieval tradition, was buried in the Catacombs under a painted vault portraying her dressed as a Roman matron as she enters paradise.

The illustrious martyrs and saints made the catacombs an attractive resting ground for early Christians looking for their intercession to access the Kingdom of Heaven. The Christian pioneers dug their way under ground creating the interconnected web that still exists today.

But the popularity of the catacombs slowly waned and when Pope Leo III moved the relics of Nereus, and Achilleus to a safer place they were slowly forgotten.

That is until Bosio stepped into the abandoned crypt 500 years later.

But after the discovery, not all explorers were well-intentioned and the catacombs became prey to tomb raiders. The vault of the Flavian Hypogeum that leads into the catacombs was stripped of the winged cherubs that once scurried up and down the painted scarlet vine.

When another famous Italian archeologist, Gian Battista de Rossi, began his excavations in the site in 1874, he found the tombs robbed of their treasures and the paintings on the walls damaged and covered in graffiti.

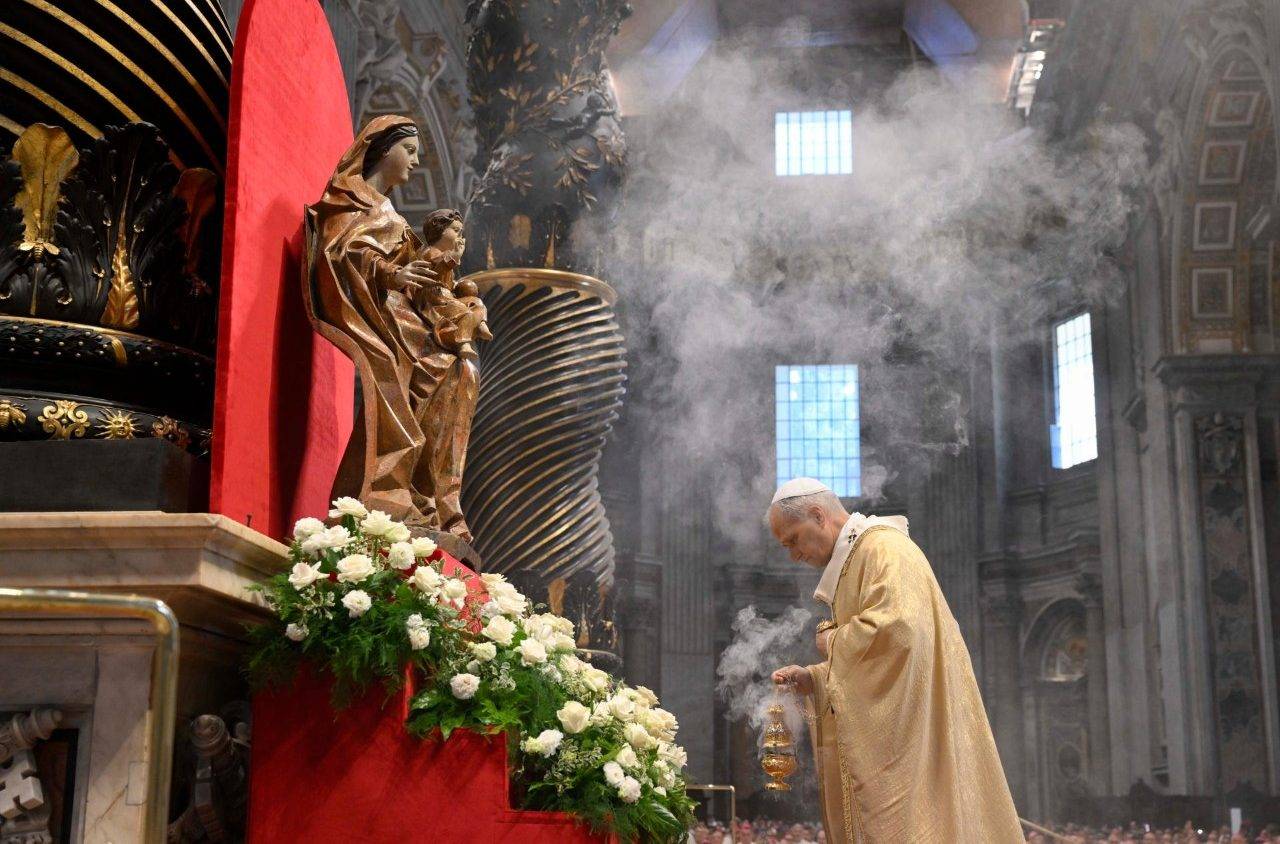

It was Rossi who asked Pope Pius IX to create the embryo of what would become the Pontifical Commission of Sacred Art that would play a major role in guaranteeing the preservation of the unique artifacts within the tombs.

In the past 25 years the Commission has monitored and cared for the 150 Christian catacombs in Italy. Fifty of the catacombs are in Rome containing more than 400 frescoes, of which about 70 are at Domitilla. The commission gave $60,000 to the German and Austrian archaeological institutes in order to restore half the paintings to their former glory, by using cutting-edge laser technology that slowly eliminates the limestone deposits that darkened the images.

Layer after layer, the vivid paintings emerged after nearly two years of work. The room of the “Small Apostles” shows the twelve followers of Christ blending in modern and dynamic poses. Underneath the vault of the tomb, Saints Peter and Paul stand next to a black square where the image of the interred is lightly etched, giving her a ghostly appearance.

The room of the “Introductio” shows Nereus and Achilleus at the center of the dome ‘introducing’ the souls of the faithful to Christ so that they may go to heaven. Painted around the room are the times when God actively intervened to help humanity, from the Lord’s hand stopping Isaac from killing his only son to Jesus multiplying the bread at Cana.

Probably the most striking of the crypts, the room of the “Bakers” holds some of the most vivid images in the catacombs. A ring circling the room shows visitors the collection, transportation and distribution of bread, a fundamental part of Ancient Roman life as well as an important symbol in Christian tradition.

High up are the images of the apostles circling Jesus and underneath the name “BOSIUS” is written in large and black characters, proving that Bosio, like many explorers, was a bit of a megalomaniac.

On the other side is a painting showing a shepherd carrying a lamb on his shoulders. The image of the good shepherd is surrounded by pagan figures, showing that though the Christian iconography is apparent the context remains rooted in ancient traditions.

Part of what makes this room so interesting is the way it shows the passage “from the civilization of myth to Christian culture,” as Monsignor Giovanni Carrù, secretary of the Pontifical Commission, said.

The Commission also created a small museum, called “Myth, Time, Life,” which collects the artifacts they found in the nearby tombs. Within there are stunning marble busts as well as images showing the restoration process.

Another majestic part of the catacomb complex is the basilica dedicated to Nereus and Achilleus. Half buried underground and half over the surface, the basilica is a bridge between the catacombs and the outside world.

“These tombs represent the roots of our deepest identity, the roots of Rome and of Christianity,” said Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi, president of the Commission, standing in the humid yet sun-bathed basilica.

Even though the catacombs are buried underground, the paintings within are a mirror of the everyday life on the surface, leaving a lasting memory “of the other face of life,” Ravasi said.

Thanks to the work sponsored by the Pontifical Commission, the witness of the early Christians who dug their way underground in search of a resting place in anticipation of Judgment day lives on. Those first Catholic pioneers searched deep within the earth, not for gold, but for Heaven so that in the words of Carrù, “death does not have the final word.”