ROME — As Iraq and surrounding areas face the destruction of many of the region’s archaeological treasures, one priest and his fellow Dominicans are preserving the area’s history and culture through an archive of Christian and other religious manuscripts.

“First, we save them (the manuscripts) physically, materially. We bring them to safety and bring them with us at the peril of our lives, of course. But, we also electronically copy them and number them and by doing this, the book or manuscript becomes immortal,” Father Najeeb Michaeel told CNA.

“In reality, I did not save this history just because I am a Christian. I saved this because I am human and everything that is human interests me, like the lives of human beings and of a human being become much more valuable when he has roots.”

Father Najeeb Michaeel is a Dominican friar and priest from Iraq. In 1990 he created the Center for the Digitization of Eastern Manuscripts to help digitize documents and archives of letters, paintings, and photos.

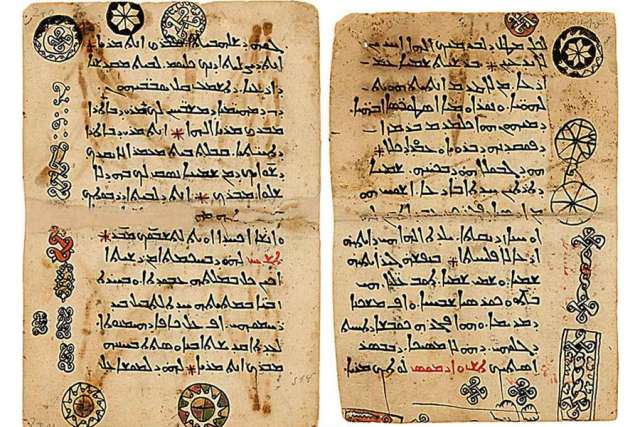

Since 2007, Najeeb and those who help him have moved and protected manuscripts from likely destruction at the hands of Islamist extremists. So far, the group has digitally preserved more than 8,000 previously unpublished manuscripts, dating from the 10th to the 19th centuries.

“Culture and civilization were born here and today it is a bath of blood and the destruction is almost complete and total, but even with all of this we keep the hope for a better future,” Najeeb said.

The question today is why we do not work to protect these villages, and to keep these things from destruction, he asked, and urged people to try to influence their governments to protect these historical places.

This collection of manuscripts “presents a small selection to say to the world, here are our roots, you need to help us, you need to help protect us. We do not have the right, as an international community, to sell arms to kill one another and not at the same time promote culture and the rights of man.”

Since 1750 the many manuscripts had been kept in the library of the Dominican monastery in Mosul. They were moved from the monastery starting in 2007, amid the backdrop of increased violence against Christians and other minorities at the hands of extremist groups.

Because of the violence, which included the killing of priests, for safety the Dominican brothers began to quietly move from their church. They continued to say Mass and the sacraments, but were physically living more than 18 miles away in the village of Bakhdida.

To not draw attention to themselves they dressed in civilian clothes and came and went discretely to celebrate Mass in caves, “like the first Christians did in the catacombs at the beginning of the Christian era,” Najeeb said.

It was during those next few years that the brothers began to progressively bring the manuscripts out of the convent in Mosul.

Then, in 2014, the Islamic State arrived in Mosul. Under threat of death unless they converted to Islam, Christians fled the city. Stopped at checkpoints on the roads, Islamic State took everything, so they were forced to leave with only the clothes they were wearing.

Amazingly, Najeeb and his brothers made it safely past the checkpoints. Then, just ten days before Islamic State invaded Bakhdida, Najeeb rescued many of the manuscripts again, this time bringing them to Erbil, where they have remained.

The documents include more than 25 subjects, including theology, philosophy, astronomy, medicine, history, and geography, many of which date back “to the 10th, 11th, and 12th century in Aramaic, which is the language of Jesus Christ, which is our mother tongue all the way to today,” Najeeb said.

They also have documents in Syriac, Arabic, Turkish, Armenian, Hebrew, Persian, and more: “All of this makes up our collection and heritage, not only Christian but also in the international communion for the whole of humanity,” he explained.

Rome hosted an exhibit and conference on just a small sample of the many photos and manuscripts June 10-17.

This exhibition was “just a small fragment of what we have in Iraq with respect to manuscripts and archives and materials and photos, because we have as well the largest deposit of photos in Iraq,” Najeeb explained.

The more than 10,000 photos “tell the story of the past: the face, the work and much more,” he continued. “Even the archaeology. And we have many archaeological documents in cuneiform as well, very ancient.”

Since 2009 the Dominicans in Iraq have also partnered with Benedictine monks, who also help with the supply of equipment and organizing internships.

Their internship program has about 10 young university students, Najeeb said, which provides “practical information for true professionals in the field of the restoration of manuscripts, for their protection and digitization, and also the process of storing them and protecting them with sophisticated technology to be able to officially protect them in a scientific way.”

Najeeb noted that preserving the manuscripts is far more important than merely having a record of history and an archive of historical objects, but something vital for the education of future generations as well.

“In fact, the manuscripts and the archives of these ancient documents make up our history and are our roots. We cannot save a tree without saving its roots. The two can bear fruit,” he said.

“So, it is important all of these archives. This history is a part of our collective archives, our past, our history. And these we absolutely had to save, as our children.”

Charles-Henri Huyghues Despointes and Alexey Gotovskiy contributed to this story.