ROME – For anyone who grew up reading Dr. Seuss, it comes as no surprise that the lessons written in his stories can be powerful tools for imparting values, especially to children.

For primary school teachers in Northern Ireland, Horton Hears a Who, the classic tale of the elephant Horton and his struggle to save the invisible “Whos”, has proven an effective way to teach forgiveness in a community long torn apart by Catholic and Protestant tensions.

“A person is a person, no matter how small,” the main line from the book, is at the heart of their application of forgiveness therapy, a relatively new and scarcely-used science aimed at understanding and applying the redeeming quality of forgiveness.

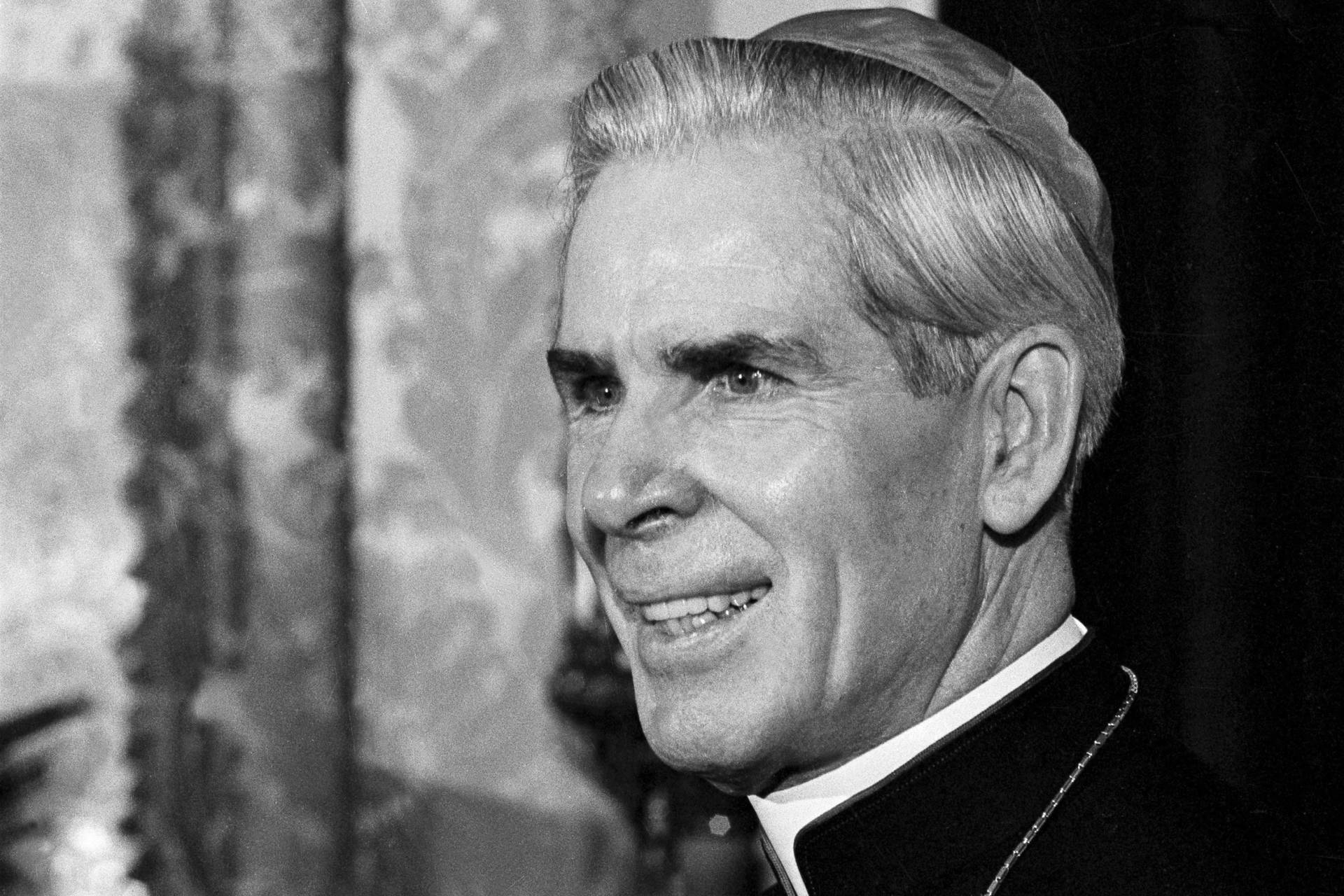

“Why did Horton help the Whos? Because they are persons, and a person has worth,” said Robert Enright, a Catholic researcher who pioneered what’s today known as “forgiveness science.” Students reading the story as part of the forgiveness program in Belfast “learn what unconditional worth means,” said Enright, who also teaches at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

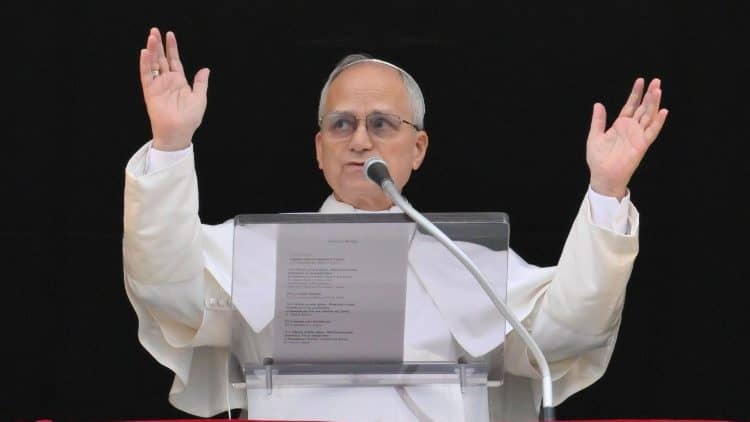

He was speaking at a conference on forgiveness that took place Thursday at the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross in Rome.

The Northern Ireland program is centered in the Holy Cross primary school for girls aged 4 to 11, located in Belfast’s Ardoyne neighborhood. The school was launched in 1969, when violent riots took over the streets of the city and Ulster loyalists burned down Catholic homes. It’s situated in what’s called a “mixed area,” with Protestants and Catholics living side-by-side and door-to-door, but divided by long “peace walls” running through their back lawns to avoid violence.

Annette Shannon, a support teacher at the school since 1996 who has been working with Enright for the past six years, wryly told the Rome conference that it “took a little while to learn about the eccentricities of teaching in a mixed faith school.”

She said that for the most part, life at the school unfolds with basic normalcy, only interrupted by what she called “a little local difficulty” each June, which is in the middle of Northern Ireland’s annual “marching season,” when Protestant groups stage processions, often through Catholic or mixed neighborhoods, which can lead to violence.

To help inoculate children from those ancient hatreds, she said, the principal of her Catholic school and the principal of the state school across the street, which is mostly Protestant, make a point of walking down the disputed road separating their campuses together – a gesture, she said, which has mostly “defused tensions.”

Those efforts, however, didn’t prepare Shannon or Holy Cross for what unfolded in 2001, four years after a cease-fire by the IRA and three years after the Good Friday Agreements.

On June 19, 2001, as students were being picked up from the school, a Protestant mob surrounded the entrance and shouted slurs at the children, parents and teachers. The angry crowd also hurled objects at the frightened school community, and clashed with police trying to provide security, resulting in at least 15 people injured.

“It’s still very difficult for me to speak about what happened,” said Shannon, although she added that a later visit to the school by Anglican Bishop Desmond Tutu “lifted our spirits.”

Shannon said that following this trauma, the school looked for ways to renew their goals and promote their values.

“Talking and using this language [of values] was not enough,” she said, “It was important to go to the root of these values.”

That’s when Enright’s forgiveness therapy came into play, and she said it quickly provided results.

“The students enjoyed the stories and getting an opportunity to talk about what they had learned,” said Shannon. “This program empowers children to solve their own problems and recognize the inherent worth of others.”

She added that the children at her school are often marginalized within the community and judged by the fact many receive a free lunch, which marks them as poor, and by their uniform, which quickly identifies them as Catholics.

“We’re now said to live in a ‘post-conflict’ society, which I suppose is nice,” She said, “but we have new problems.”

Many of the children at Holy Cross, she said, have “first-hand knowledge of abuse, suicide, violence, and family breakdown,” making them particularly sensitive to the topics of forgiveness and worth, saying that with Enright’s program, the school is able to “encourage young women about the importance of forgiving in their life.”

Shannon is well aware that the program can only plant a seed, but says at the end of the semester she notes that children remember the stories they were taught and the messages within, and also the way their opinions and remarks were valued during the discussions.

“These are views that are important and powerful enough to be a force to bring change in their community,” she said.

Though she basically steered clear of commentary on Northern Ireland’s political situation, she did draw a conclusion from her school’s experience with political relevance.

“Our politicians won’t use the language our children use. They are inflammatory, attacking or defending one side or another,” she said. “These children can teach them about respect, duty and, above all, forgiveness.”

According to Enright, forgiveness therapy is also having an effect outside the boundaries of the school.

“In Belfast, parents who use the material meant to teach their children about forgiveness, benefit from it more than anyone else,” he said.

Among the many benefits of applying forgiveness in our day-to-day lives, Enright lists the ability to teach adults and especially teachers that forgiveness can be a path to peace, to be passed down through the generations.

According to Enright, if given a chance, forgiving can benefit all sorts of good causes, including peace-building and ecumenism. To quote Dr. Seuss’s book: “We’ve GOT to make noises in greater amounts! So, open your mouth, lad! For every voice counts!”