ROME — Pope Francis on Saturday urged one of the Catholic Church’s biggest but most contentious missionary movements to respect different cultures and not try to conquer souls as it spreads the faith around the world.

Francis headlined a big rally marking the 50th anniversary of the Neocatechumenal Way’s arrival in Rome. The community founded in Spain in the 1960s seeks to train Catholic adults in their faith and each year sends out families on mission around the globe.

The Vatican under the past two popes in many ways kept the Way at arm’s length because of its unusual liturgical practices, which include celebrating Mass on Saturday nights, and its occasionally divisive presence in dioceses. The Way’s statutes were only approved in 2008.

Francis though is less a liturgical purist and has insisted the Church be more missionary in nature. As a result, he has seemingly embraced the Way, albeit with regular warnings, including on Saturday, to work for and not against unity in the Church.

Francis warned the 34 new missionary groups heading out not to dictate to others or follow pre-ordained scripts, but to accompany the faithful patiently. He urged them to love and respect the cultures and traditions of other people.

“We go forward together, without isolating ourselves or imposing our own pace, united as a Church, with pastors and all our brothers,” Francis told the crowd that was expected to number more than 100,000 from 135 countries.

He recalled that when Jesus urged his disciples to find more believers “He didn’t say conquer, occupy, but rather make disciples, share with the others the gift you have received.”

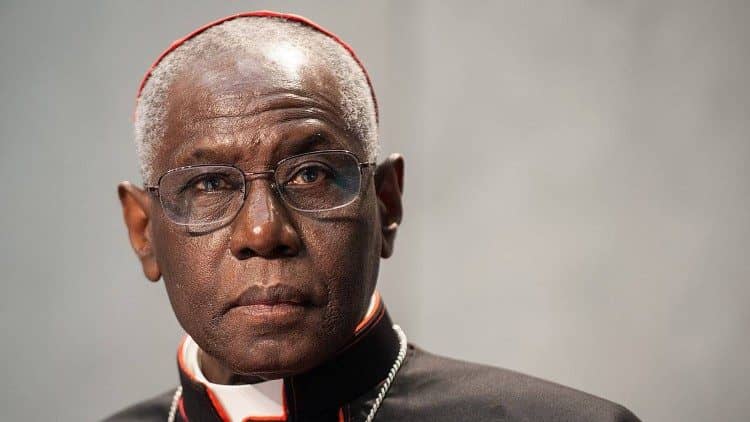

Seated behind him were an impressive array of cardinals and bishops, a sign that for all its controversy the Way has its high-ranking supporters. Kiko Arguello, the Way’s charismatic, guitar-strumming co-founder, made a point to identify by name each of the half-dozen Vatican-based cardinals on hand, giving each one rousing rounds of applause.

While appreciating the movement’s religious zeal, bishops in Japan, the Philippines and elsewhere in Asia and Europe have accused the movement of wreaking havoc in their dioceses and have tried to limit the Neocatechumenals’ activities, shutting their seminaries and complaining to the Vatican. Critics point to the Way’s secretive, sect-like ways and of alleged cultural insensitivity by missionaries, who by some estimates number 1 million.

Most recently, the Way has been in the spotlight in the U.S. Pacific territory of Guam after its main supporter on the island, Guam Archbishop Anthony Apuron, was removed to stand trial at the Vatican on sex abuse charges.

Apuron’s replacement, heeding criticism by ordinary faithful on Guam, placed restrictions on the Way, mandating a yearlong “pause” in the creation of new prayer communities, ordering that its members obey Vatican rules in celebrating Mass and launching a review into the quality of their training as Catholic teachers.