Although not yet announced by the Vatican, it has been confirmed by numerous sources that Pope Francis plans on visiting Myanmar – also known as Burma – in late November.

The trip will be in conjunction with a visit to neighboring Bangladesh, and is a last-minute change after plans to visit India fell through due to hesitation from the Indian government.

Francis has been following the situation of Myanmar’s Muslim-minority Rohingya population, who have faced rising levels of persecution, including rapes and extra-judicial killings.

A UN report in February described their situation as a possible “genocide” and a set of “crimes against humanity” in Myanmar, where the Rohingya are officially categorized as Bengali “interlopers” despite the fact they’ve lived in Rakhine for generations.

RELATED: Rohingya Muslims tell of abuses during army crackdown

Myanmar’s government, now led by Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, has denied most of the claims.

The pope has vocalized his concern for the Rohingyas on several occasions, most recently last February, when he said, “They have been suffering, they are being tortured and killed, simply because they uphold their Muslim faith.”

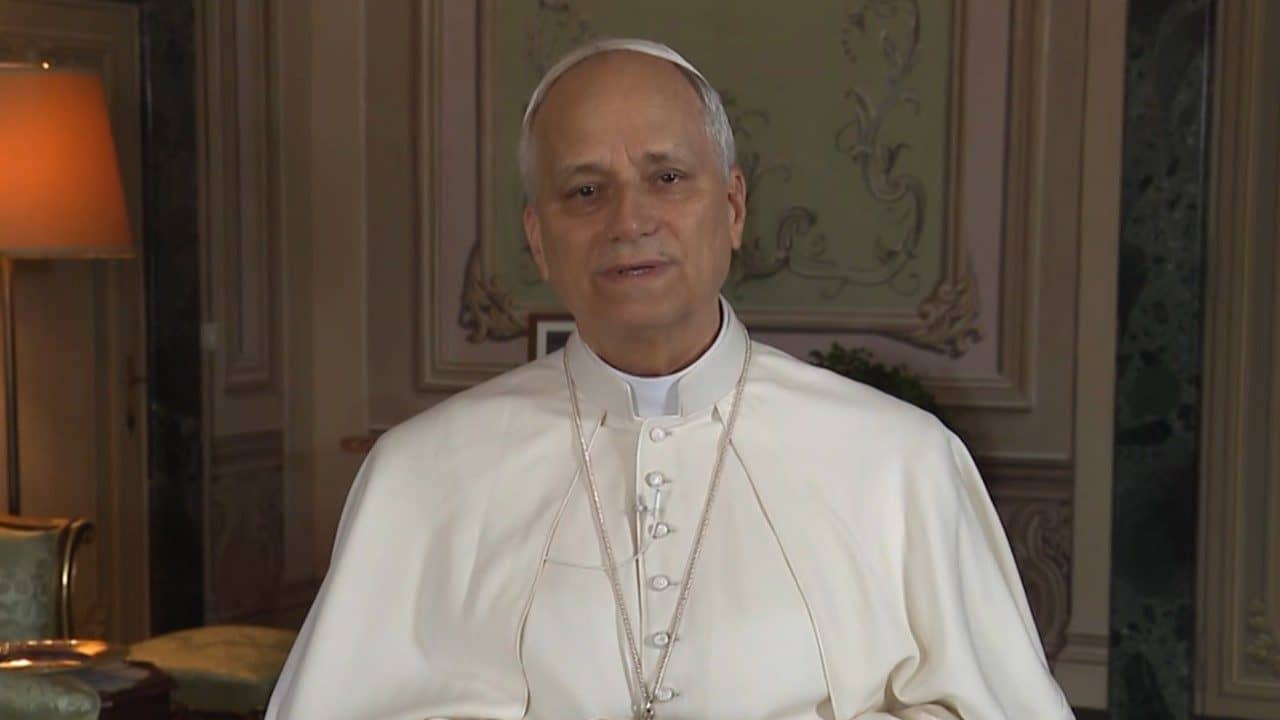

The Archbishop of Yangon, Cardinal Charles Bo, has called for the allegations against the government to be “fully and independently” investigated.

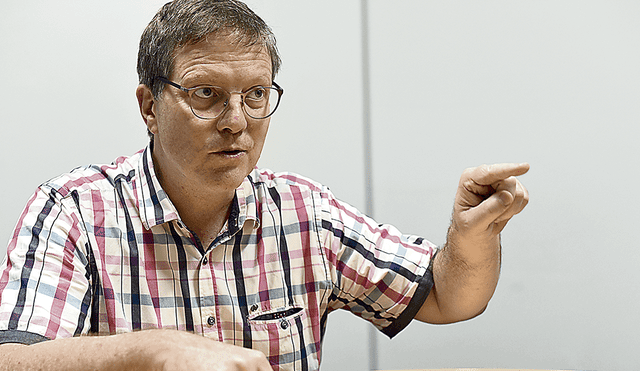

Mark Farmaner, the director of Burma Campaign UK, says Bo is the only senior voice within the country to speak for the rights of the Rohingya.

“In the past, the Catholic Church pretty much kept its head down, for fear of provoking a backlash against Catholics,” Farmaner said.

Founded in 1991, Burma Campaign UK is one of the leading international organizations seeking reform in the country.

(“Myanmar” is the name given to Burma by a military regime in 1989. It is used by the United Nations and the Vatican. Several countries, including the United States and the United Kingdom, continue to use Burma officially. Suu Kyi stated the use of either name is allowed in 2016, and both American and British diplomats have used both designations. “Burma” is considered more inclusive by the country’s minorities.)

The organization campaigned for the release of Suu Kyi when she was under house arrest, but has also drawn attention to human rights abuses taking place under her government.

He said the success of the pope’s visit should not be judged by how many people turn out to see him, or whether he speaks out on the Rohingya and other human rights issues.

“We need to see practical results that will deliver long-term change on the ground,” Farmaner said. “If Pope Francis could persuade the government to work with him on implementing programs to promote religious tolerance, such as the United Nations Rabat Plan of Action on religious hatred, then his visit truly will be a success and leave a lasting legacy.”

(Released in 2013, the Rabat Plan of Action prohibits the advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence. The plan seeks to balance international rights of freedom of expression with prohibitions against incitement.)

Farmaner spoke to Crux about his thoughts on the expected papal visit.

Crux: What were your initial thoughts when you heard Pope Francis was planning on visiting Burma?

Farmaner: Pope Francis is likely to face a challenging time. On the one hand, he will be expected to speak out on human rights violations, including against the Rohingya, but if he does, he will displease Aung San Suu Kyi’s government and upset Buddhist nationalists who may even hold protests against him. Catholics in the country may be afraid that they could face a backlash if Pope Francis takes a moral and principled stance for the Rohingya.

What is the current situation with the Rohingya population? Pope Francis has spoken about them a few times – often in unscripted moments. What would you like to see him do or say about the Rohingya while he is there?

Frankly, the government and military are unlikely to listen to Pope Francis on the Rohingya issue, but it would be positive if he could influence Catholics in Burma to challenge prejudice and promote more tolerance. The resurgence of Buddhist nationalism was initially targeted at Rohingya and then all Muslims, but now it is also impacting Christians. People of all faiths need to work together to challenge prejudice, not hide within their own faith communities hoping they won’t be the next target.

Can you tell us what the situation is like for Christians in the country?

It’s a mixed picture. In the cities, Christians have established churches and generally face little prejudice, although many Burmese Buddhists still see Christians as ‘them’ and not properly Burmese. They can face problems seeking certain kind of employment.

The main problems Christians face are in ethnic areas where they are refused permission to build churches or crosses and can have buildings torn down by authorities, and face more severe prejudice.

You mention Christians in the “ethnic areas”: Can you elaborate on what the ethnic situation is like in Burma?

Burma is a multi-ethnic and multi religious country, but predominantly ethnic Burman and Buddhist. Some of the larger ethnic groups, such as Karen, Kachin, Chin and Karenni have large numbers of Christians. The root cause of conflict and dictatorship in Burma has been the refusal of central governments, both civilians and military, to accept other ethnicities and religions as equal. Instead, they have tried to ‘Burmanise’ ethnic people and use force against them when they resist.

The pope named Bo as Burma’s first cardinal in 2015. Has Bo been an effective voice for positive change in Burma? Is there more the Catholic Church can do?

Cardinal Bo has been pretty much the only senior voice within Burma who has spoken up for rights for the Rohingya, and has spoken out on other problems as well. In the past, the Catholic Church pretty much kept its head down for fear of provoking a backlash against Catholics. It would be positive if the Vatican could provide the expertise and resources to help the Church in Burma do more to promote religious tolerance at the grassroots level.

Earlier this month, the first Vatican ambassador arrived in Burma, after the Holy See and the government established full diplomatic relations in May. Do you have any hopes or concerns about this diplomatic activity?

The new Vatican Ambassador must be willing to speak truth to power, not just focus on securing good diplomatic relationships.

There has been a lot of talk about the recent changes in Burma, especially since Aung San Suu Kyi’s party won national elections and formed a government. Burma Campaign UK has been highlighting the abuses that are still taking place, and the continuing domination of the country’s institutions by the military.

Can you give us your assessment of what has happened in the country over the past few years, during the “liberalization” of the country?

The political transition in Burma has been away from direct military rule but not to democracy. There is now a hybrid government, part civilian, part military. Unfortunately, neither the civilian part of the government led by Aung San Suu Kyi, nor the military part of the government are respecting human rights.

What would you consider the minimum requirements for a successful visit by Pope Francis?

The success of Pope Francis’s visit should not be judged by how many people turn out to see him or whether he speaks out on the Rohingya and other human rights issues. We need to see practical results that will deliver long-term change on the ground.

If Pope Francis could persuade the government to work with him on implementing programs to promote religious tolerance, such as the United Nations Rabat Plan of Action on religious hatred, then his visit truly will be a success and leave a lasting legacy.

Is there anything else that should be a concern about the trip?

It is quite likely that Pope Francis will face protests by Buddhist nationalists when he visits, because of the comments he has already made about the Rohingya.

Can you tell us more about these Buddhist nationalists, and their influence with both the civilian government and military?

When the military stepped back from direct control of Burma in 2011 they used a proxy political party to run the government, led by a former general, Thein Sein, who became President. Faced with the prospect of future elections and the popularity of Aung San Suu Kyi and her party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), Thein Sein turned to Buddhist nationalism to try to undermine support for Aung San Suu Kyi and build support for himself.

He allowed nationalists free reign to organize, incite and carry out violent attacks against Muslims, used their language, and passed laws proposed by Buddhist nationalists. They backed his party at the election in 2015, but the NLD won a landslide anyway.

However, NLD leaders have also pandered to the nationalists and some share their nationalist views. Aung San Suu Kyi did not field any Muslim candidates in the election, did not appoint any Muslim government ministers, and kept in place the laws nationalists wrote, including the policies and laws discriminating against the Rohingya.