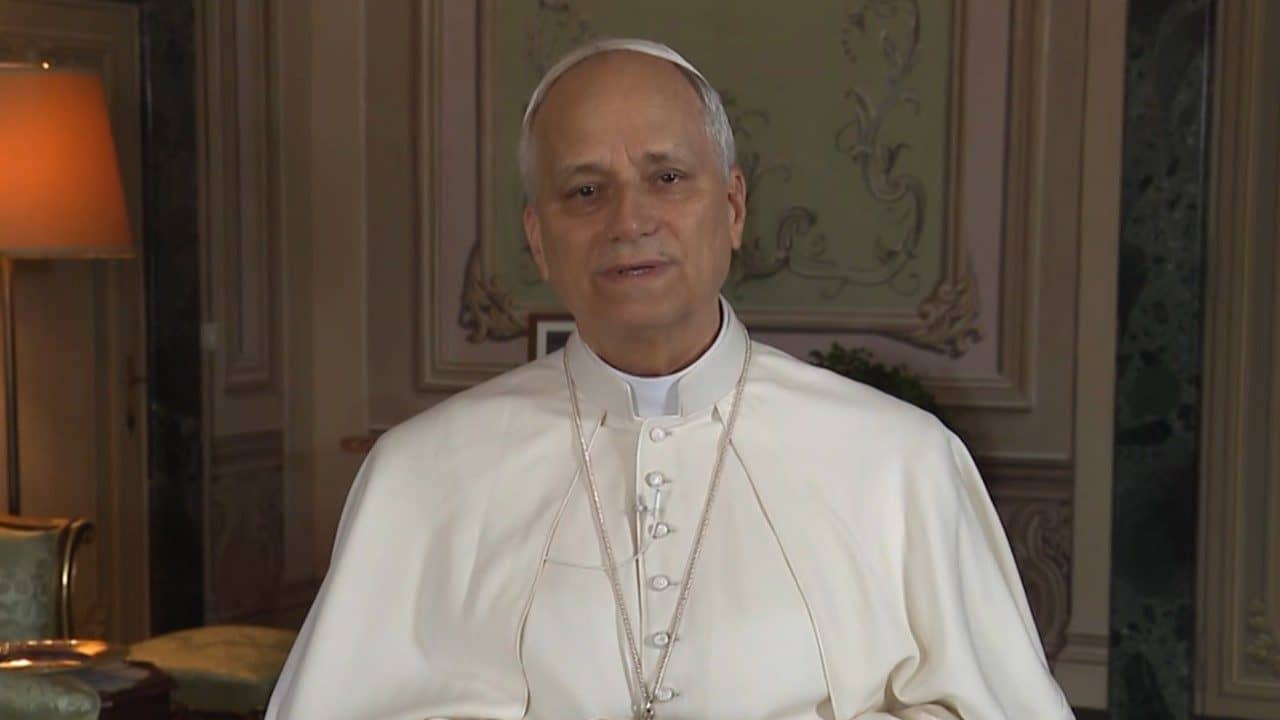

DUBLIN, Ireland – A month before Pope Francis touches down on his first visit to Ireland, Dublin Archbishop Diarmuid Martin says the entire nation – religious or not – is interested in what the pontiff has to say.

“The tickets were booked out within days. The big problem – both in Dublin and in Knock – there is no room to take in more people, and more people want to come,” Martin told Crux.

The pope will travel to the country Aug. 25-26 for the final two days of the week-long World Meeting of Families.

Francis will be coming to a very different Ireland than the one that last welcomed a pope in 1979, when millions came to see John Paul II.

The clerical abuse scandal has greatly damaged the reputation of the Church: Not only have same-sex marriage and abortion been legalized, but recent surveys show about half of Irish people under the age of 30 don’t even identify as Catholic.

Martin said young people were “horrified” by the scandal, and one of the challenges for the Church in the future is to learn to re-engage them.

“These young people are extremely generous, committed, with high principles, and somehow the Church with all this presence in the educational system hasn’t managed to create this bond between their own idealism and the message of Jesus Christ,” the archbishop said.

Martin said he didn’t think Francis could come to Ireland and not address the scandal, but he was non-committal on whether the pope would meet with abuse victims.

“One of the big difficulties is the number of victims and the category of victims are very different than in other places. In the past he has met people who are victims of child abuse by priests. But the victims in Ireland are a broader group. He is here for 36 hours. I wouldn’t rule it out,” he said.

In those 36 hours, Martin said Francis can’t perform miracles for the Irish Church, but the archbishop said the pope does have a unique ability to connect with everyday people.

“He has the ability himself to go anywhere in the secular world and be unashamed of speaking about Jesus Christ. People think this is a politician who is coming, or this is a pop star that is coming – he is coming as a man of God. His real talent is that he is captivated personally by the message of Jesus Christ,” Martin said.

Martin sat down with Crux on Thursday at his residence in Dublin, and following are excerpts of that conversation.

Crux: How is this going to be different than previous World Meetings of Families?

Martin: It is a very wide range of topics. I would say it is going to be an interesting three days for somebody who goes there. We did this a few years ago at the Eucharist Congress [held in Dublin in 2012] here in Ireland. Many priests came to me afterwards and said “When we went and saw the RDS and what was happening, we were sorry we didn’t become more enthusiastic earlier.”

The people came and found there was a lively Irish Church which we can be very proud of.

If you look at this event, the reaction of the people of Ireland is very positive. The tickets were booked out within days. The big problem – both in Dublin and in Knock – there is no room to take in more people, and more people want to come.

Why do people want to come? There are people who will see any pope. There are people who like Pope Francis. The interesting thing is that right across Ireland people are interested: The fervent Catholics, the weaker Catholics, those who are against the Church. They are all interested in this man, and what he will say, and what can he say, to the Irish Church.

To ask a man in 36 hours to leave a prevalent impact on the Irish Church and Irish society is hard, but he has the ability himself to go anywhere in the secular world and be unashamed of speaking about Jesus Christ. People think this is a politician who is coming, or this is a pop star that is coming – he is coming as a man of God. His real talent is that he is captivated personally by the message of Jesus Christ.

It is a time in Ireland – people say it is a post-referendum Ireland – but it goes deeper than that. I think that this a period right across Ireland where people are reflecting on where our future will be. We have gone through changes, many of them positive, but we have lost a lot. Where do we want to go? And how can we all work together in a pluralist, diversified Irish society? What do we want for the next generation of Ireland, and how do we build those building blocks of solidarity that belong in society?

The question for the Church is: How can the Church be authentically Church in this changed culture. It has to recognize the culture has changed – not necessarily adapt to the culture – but recognize that is the culture we live in.

I don’t think the pope intends to replicate the Church of the past in Ireland, which had many serious problems. And we have to ask this of ourselves before we can move on, and I think the Church in Ireland in the years to come will be a different Church.

The biggest challenge for me is that there is a generational difference. The main body of practicing Catholics – and the main body of the leadership of the Church – belong to a generation which is very different than the generation of young people who will be the ones setting the tone.

Many of these people have been educated in Catholic schools, and you go along to Mass and you don’t see them.

These young people are extremely generous, committed, with high principles, and somehow the Church with all this presence in the educational system hasn’t managed to create this bond between their own idealism and the message of Jesus Christ.

I use the example of the pope not being able to give the Church a new roadmap, but he will be able to give indications. But the big danger is that the Church will continue to print roadmaps on paper, whereas roadmaps today are interactive.

There are movements of young people, but they are small. The main body of young people has drifted away, not just from church attendance, but from understanding the relevance of the message of Jesus to the modern world.

Looking at the recent abortion referendum in May, it was only 15 years ago that nearly half of the population voted in another referendum to strengthen the restrictions on abortion.

I would say there is still a strong pro-life view. Even those who voted yes, you can’t say it was a homogenous group of people who voted to have abortion on demand. It was anything but. Even listening to the political debate, the government was very worried that any indication that widespread abortion was to be introduced into Ireland, it would probably not go. You had people voting yes, but they were voting yes to something very restricted.

What affect do you think the clerical abuse scandal had in the secularizing of Irish society.

There is no doubt it alienated a lot of people, and a lot of young people. People don’t seem to think young people were really interested in that, but the young people were horrified.

There were the institutions that were being run by religious orders; there were mother and baby homes; there were the Magdalene laundries; there was the abuse by individual priests. The numbers went through this at every stage was huge. You have to ask yourself was there something in Irish Catholicism that fostered this harshness which existed in the Irish Church.

I ordained two Salesians two Sundays ago. Don Bosco, the founder of the Salesians, in the middle of the 19th century founded his own pedagogy for dealing with young people where punishment was marginalized. And here we had these really harsh regimes. Sometimes people said well nobody else provided these services, but I can remember saying even way back that no one will thank you for providing poor quality service.

We had a system that was very much black-and-white: Sins were sins, and mortal sins were mortal sins and venial sins were venial sins, and the priest knew which was which. Now people have rejected that. There is a vague understanding of what sin might be about. This is again what the pope can come and say people don’t live in the black-and-white world, and we have to engage people in the grey world – in the everyday world – and help them come to a deeper understanding of what the teaching of the Church is about. Not by imposition, and not by saying anything goes.

Is the pope going to address the abuse crisis?

I don’t think the pope can come to Ireland and not address it.

Do you think he will meet with victims?

One of the big difficulties is the number of victims, and the category of victims are very different than in other places. In the past he has met people who are victims of child abuse by priests. But the victims in Ireland are a broader group. He is here for 36 hours. I wouldn’t rule it out.

There is a lot of anger still present. What happened in Chile is an interesting thing. The anger emerged very strongly because the pope – as he said himself – the advice had put him on the wrong track. This is one of the challenges he will have to face here.

There are some people who say we have the best child protection policies in the world. And that is probably right. But to say that therefore abuse is a thing in the past is wrong. The wounds are there; they are very deep; and they haven’t been healed.

What is your hope for the long-term effects of the World Meeting of Families?

I would hope that the pope would create an atmosphere where people of different backgrounds begin to say, let’s work together. Let’s recognize the Church’s faults, but let’s also recognize the great contribution of the Church and the message of Jesus Christ to society. And let’s very clearly begin to strengthen the Church not to be what it was in the past, but something different for the future.

Then it is up to the Irish Church itself to take up that message.