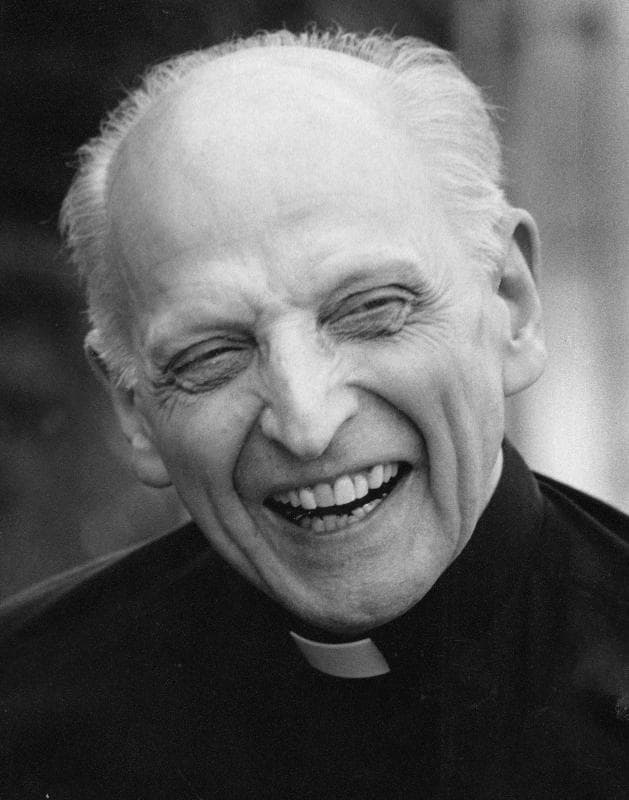

ROME – On Tuesday, perhaps the most beloved and, simultaneously, the most controversial Jesuit of the last half-century officially will become a candidate for sainthood, when the first phase of a cause for Spanish Basque Father Pedro Arrupe, who led the order from 1965-83, opens in Rome.

Not since Pope Clement XIV suppressed the Jesuits in 1773 had the order found itself in the eye of the storm quite like it did during Arrupe’s tenure, which overlapped with the period immediately following the Second Vatican Council (1962-65).

Under Arrupe, the Jesuits embraced the “spirit” of Vatican II, enthusiastically pursuing reform on multiple fronts, throwing themselves into social action and the option for the poor, and often becoming the intellectual and spiritual heroes of Catholicism’s liberal wing.

That orientation made the Jesuits heroes to some and question marks for others, including some of the key figures in St. John Paul II’s Vatican. When Arrupe suffered a debilitating stroke in 1981, John Paul bypassed his choice as interim leader, American Father Vincent O’Keefe, to tap Italian Jesuit Paolo Dezza, who had taught the future pope at the Gregorian University. Many Jesuits took it as a papal smackdown and a personal affront to Arrupe, opening tensions between the Vatican and the Church’s largest and most influential religious order that have taken decades to ease.

Today, however, Spanish Father Pascual Cebollada, the official in charge of Arrupe’s sainthood cause, says the passage of time has put those tensions in the proper perspective.

“We can look at Arrupe and see that for himself, he wasn’t ideological at all, not at all,” Cebollada said. “I think that because of his spiritual and religious qualities, the size of his character is too big to be measured by ideology.”

Cebollada spoke in an exclusive interview with Crux at the Jesuit curia in Rome, the order’s headquarters located a stone’s throw from St. Peter’s Square.

“You really find a man who loved the Church, the Holy See and the pope immensely, and it’s absolutely impossible to think that he would have thought of disobeying or going against what the pope was saying,” Cebollada said.

Above all else, Cebollada insisted, Arrupe was a “man of God.”

“People, when they met him, would say, ‘He’s a saint, he’s someone extraordinary,’” he said. “There was something inside him we call ‘familiarity with God.’ You could feel it.”

After that, Cebollada said, Arrupe was also a man of the Church, especially in his commitment to implementing Vatican II.

“When he was elected General of the Society of Jesus, he just said, ‘Okay, in the time of Ignatius it was Trent, now it’s Vatican II, so let’s go with Vatican II. This is my aim, my mission … it’s the mission I’ve received from the Church,’” Cebollada said.

Arrupe’s sainthood process officially opens Tuesday with a Mass to be celebrated in the Lateran Apostolic Palace by Cardinal Angelo De Donatis of Rome, the diocese responsible for collecting testimonies and spearheading the effort in its early phases. Venezuelan Father Arturo Sosa, the current Jesuit general, has invited members of the order all over the world to follow the Mass and to pray for the cause.

The following are excerpts from Crux’s interview with Cebollada, which took place Feb. 1.

Crux: What’s the legacy of Father Arrupe?

Cebollada: I would say the first point is [that it’s] hidden, in the sense that it’s a spiritual legacy. I myself met him twice, once before being a Jesuit. When people met him, when they talked to him, when they listened to what he had to say, when they prayed with him, they felt something special. He had a wonderful religious and spiritual quality.

That’s why people, when they met him, would say, ‘He’s a saint, he’s someone extraordinary.’ There was something inside him we call ‘familiarity with God.’ You could feel it. He was a man of God, with a faith rooted in times of secularism, difficulties, ambiguities, this ‘New Age’ spirituality. Ultimately, it was rooted in Jesus Christ.

The second part of his legacy would be the Church, because he was so deeply a man of the Church. When he was elected General of the Society of Jesus, he just said, ‘Okay, in the time of Ignatius it was Trent, now it’s Vatican II, so let’s go with Vatican II. This is my aim, my mission … it’s the mission I’ve received from the Church.’”

As Father [Peter Hans] Kolvenbach said on the anniversary of his birth in Bilbao, he was a marvelous prophet of conciliar renewal. All that’s part of his legacy, and it remains.

You said Arrupe was a man of the Church, but in his own time he was deeply controversial. As you look back at what happened in 1981 when St. John Paul II appointed his own leadership of the Jesuits, what sense do you make of it now?

Many years later, thank God we now have a calm time when we can look at all these events in a different way. Many people who were with Arrupe when they were younger are still alive, of course, and took part in these controversial issues between the Society of Jesus and the Holy See. It’s important to remember it wasn’t only Arrupe, and it wasn’t only the pope … it was the Society of Jesus and the Holy See, which is more complex. Now we have a better perspective on everything.

First of all, I would hope that looking at Arrupe and not ‘hijacking’ him – that may be a bit exaggerated, but I mean not misappropriating him. Before, people would say ‘Arrupe has said this, Arrupe has done that, Arrupe has suffered this and that,’ and it was often a bit ideological. Now, I think we can be free of this ideology. We can look at Arrupe and see that for himself, he wasn’t ideological at all, not at all.

Coming back to what we spoke about at the beginning, I think that because of his spiritual and religious qualities, the size of his character is too big to be measured by ideology … This should help us better understand the entire period, which was so controversial and agitated, not just for the Jesuits but for the whole Church.

From the point of view of Arrupe, when you read what he wrote at that time, when you speak with the witnesses who talked with him about what was going on in that period, you really find a man who loved the Church, the Holy See and the pope immensely, and it’s absolutely impossible to think that he would have thought of disobeying or going against what the pope was saying. He was not ambiguous, Arrupe, not at all. When all these things happened, I’d like to reaffirm that from Arrupe’s point of view it was never his intention [to disobey.]

The pope came from Eastern Europe, and he had his own experience before taking office. When Arrupe was elected general, he came from Japan. He had been there from 1938 to 1965, and before he’d been in exile in the Netherlands and Belgium … He had different origins and different ways of doing things from what Pope John Paul II had lived.

Of course, I’m not putting them at the same level. The pope is the pope, and Arrupe was very, very clear on that. Even when things were becoming difficult for the Society of Jesus, Arrupe never stopped going down to the entrance of the Jesuit curia [in Rome] to say hello to the pope as he’d pass by in his car on the way to visit Roman parishes on Sunday afternoons. It would just be maybe five seconds, seven seconds, but he always came down just for that … it was a kind of love for the pope and the Holy See, for the representative of the Church. That was Arrupe.

Both of them were charismatic persons, I think. Both loved to go for journeys, both traveled a lot, because evangelization was a common denominator for both of them. Maybe in a different way, but really this was a common fact.

You mentioned Arrupe’s experience of Japan. How did the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki affect him?

First of all, Arrupe’s first contact with suffering wasn’t in Japan. Even when he studied medicine in Madrid, he used to visit the poor of the town he was in every Sunday, just to help. He had always wanted to help, especially the poor.

When he joined the Society of Jesus, he always asked to go on the missions, and finally he was sent to Japan. Between parentheses, Pope Francis also wanted to go to Japan, but Arrupe told him his lungs weren’t good enough so he’d better stay in Argentina.

In effect, Arrupe is responsible for putting Bergoglio on the path to the papacy?

In this sense, yes!

Arrupe was sent into exile before going to Japan, and that’s not easy for anybody. He was a refugee, since he had to leave Spain because of the civil war. Then he went to Japan, and had this terrible experience of Hiroshima. He had also been in jail for two months in Japan, as was considered suspect during the war because he wasn’t Japanese. Exile, jail, Hiroshima … he wasn’t at all naïve about suffering.

You know, Arrupe had a reputation of being too optimistic. Some said he didn’t know how to cope with real problems enough to organize the Society of Jesus, he’s too charismatic. Okay, he was optimistic and he had a lot of hope, but it wasn’t a naïve optimism. These experiences prevented that. A man who’s been in Hiroshima can’t be naïve.

In regard to the poor, he had a very spontaneous, natural and normal – I mean non-ideological – relation to the poor. He loved the poor, and he also wanted us to love them personally. He didn’t want us to love them just in our speeches or with our great institutions, but to know the poor personally and to live as far as we could with them.

What do we know about the personal relationship between Pope Francis and Arrupe, and would you say that Francis as pope is a reflection of Arrupe’s influence?

Surely he was here in Rome in 1974 for the 32nd General Congregation of the Jesuits. He was 38, so rather young, and he’d already been appointed provincial by Father Arrupe in Argentina, which means Arrupe had confidence in him. They met several times in Buenos Aires and here in Rome.

We have a couple of testimonies from Pope Francis. Shortly after coming here to Rome as pope, he went to the Church of the Gesù where Arrupe is buried. He asked for a bunch of flowers, because he wanted to pray at Arrupe’s tomb. He went there and he prayed in silence and offered the flowers to Arrupe. This was very significant.

Then a year ago he was in Peru, and he joined the Jesuits as he normally does when he travels. He said to them that we have the grace of the generalate of Father Arrupe. What he meant is that he was the one who discovered Ignatian spirituality for us Jesuits and for the Church. He was the one who rehabilitated discernment for us and for the Church.

I guess he loved Arrupe, he loved Arrupe, and he always felt at his side.

Secondly, what is his influence? It is a common influence of Ignatius of Loyola, a common influence of the Exercises, of the constitutions. This is the great influence, both of them felt it, so they share this influence.

And, neither man has any fear. They’re both courageous. I think that when Arrupe feels that he is placed here by God, by providence, by the Church, he says let’s do it. I guess that what Pope Francis says is similar, so go on.