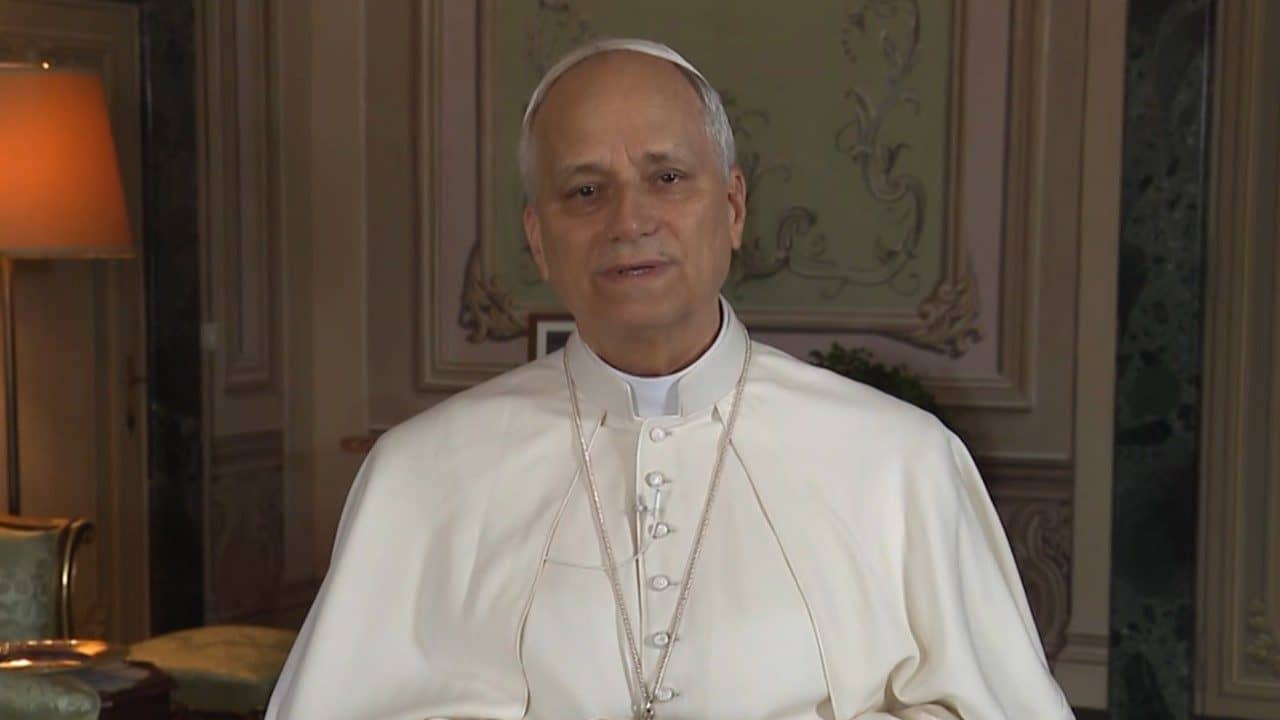

In May, Joseph Meaney’s heart went into V-tach, a dangerous ventricular arrythmia that can be fatal.

After he got to the hospital, his wife asked that he be anointed, since he was in danger of death. However, there were no Catholic chaplains on staff, and COVID protocols prevented a local Catholic priest from visiting patients at the hospital.

“The hospital COVID policy prevented my wife from visiting or a priest from coming in from outside. They did have chaplains on staff who could visit me, but none was a Catholic priest,” Meaney recalled.

“The medical staff were friendly and treated me well, but the very restrictive policies of the hospital tied their hands and inflicted suffering on me and my family. I can’t imagine how bad it would have been if my condition had proved untreatable, and I was forced to die isolated from family and the sacraments,” he told Crux.

Meaney is the president of the National Catholic Bioethics Center, based in Philadelphia.

His experiences – and those of thousands of patients in hospitals and care facilities across the country – have helped shape a call for the “right not to be forced to die alone.”

“There is consensus among almost everyone that the passage from life to death is a terrible moment and the dying should be helped in every way possible,” Meaney said. “Everyone agrees that forcing persons to face death without their closest loved ones present or the assistance of the sacraments is a terrible burden. The question one must answer is if there was/is sufficient justification for these strict restrictions?”

Currently, COVID-19 social distancing restrictions at medical and care facilities often limit visitation rights for family and chaplains.

“It is my impression that the novel situation and circumstances surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic did justify new restrictions, but compassionate exceptions should have been made for those who were dying. In the USA and elsewhere they did not run out of PPE, and it would have been possible for many persons to receive comfort and spiritual assistance in person in a safe way who did not,” he continued.

“For Catholics and many other believers there are things worse than death or more important than reducing the risk of death,” Meaney said. “When it comes to facing death believers frequently see the need for spiritual and emotional preparation as being very important, in fact, more important at the end than medical care or safety precautions.”

What follows is Meaney’s conversation with Crux.

Crux: What do you mean when you speak about a right to not be forced to die alone?

Meaney: There is consensus among almost everyone that the passage from life to death is a terrible moment and the dying should be helped in every way possible.

Certain hospitals and health care facilities, particularly nursing homes for the elderly, put into place draconian visitation restrictions as a reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic. The result of these policies was the prevention of family members or clergy from being able to come to the bedside of many dying persons as they wished. Large numbers of people had only medical staff around them when they died. These were preventable tragedies and especially serious from a spiritual perspective since the last rites can only be given in person and can be essential for preparing a person for death and their souls for eternal life through the forgiveness of sins.

Everyone agrees that forcing persons to face death without their closest loved ones present or the assistance of the sacraments is a terrible burden. The question one must answer is if there was/is sufficient justification for these strict restrictions?

How do we balance this right with the need to make sure a very deadly virus doesn’t spread?

That is a key question. At the start of the pandemic there was a unique crisis. Scientists and health care providers did not know how deadly the virus would be or how easily people could spread it.. Experts feared there would not be enough personal protective equipment (PPE) available to keep frontline health workers safe as they treated patients. Lockdowns were imposed on all of society in a very unprecedented way to prevent the rapid spread of the disease.

In bioethics key considerations include the circumstances surrounding decisions. It is my impression that the novel situation and circumstances surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic did justify new restrictions, but compassionate exceptions should have been made for those who were dying. In the USA and elsewhere they did not run out of PPE, and it would have been possible for many people to receive comfort and spiritual assistance in person in a safe way who did not.

I believe a big problem with the pandemic response in some places was a mistaken hierarchy of values. Some public health officials and health care administrators simply prioritized the physical safety and reduction of viral contagion over almost any other consideration. This is reasonable at first glance, but it does not stand up to closer scrutiny when pushed to the extreme limits. Here is an example. We can all agree that one should not put our lives at risk. Some people might conclude this means they should not drive or ride in an automobile since there is an extremely small but real risk of a fatal traffic accident… This mental exercise could be multiplied. The point is that there is no way to reduce risk to zero, and some measures or restrictions to reduce risks create graver problems than they resolve. A key practical maximum is that the cure must not be worse than the disease.

What I believe is lacking is a compassionate understanding of human rights. For some secular humanists it could be indeed true that there is no higher value than preserving a person’s physical life and they do not believe in life after death. It is their right to hold this belief, but they do not have the right to impose it on others. For Catholics and many other believers there are things worse than death or more important than reducing the risk of death. The Christian martyrs chose to refuse to sin rather than to save their physical lives.

When it comes to facing death believers frequently see the need for spiritual and emotional preparation as being very important, in fact, more important at the end than medical care or safety precautions.

Do you think the spiritual needs of the dying have been side-stepped during this pandemic?

It was very interesting to see what was deemed “essential” and “non-essential” during the lockdowns. Clearly, some activities had to continue or everyone would die-like access to food and water. Some services could not be suspended like pharmacies and medical emergencies, but elective surgeries and medical services could be postponed. The list continued to grow. Fuel stations and police or fire protection had to remain operational.

What became highly problematic was when certain stores were granted “essential” status and other indoor gathering places were not. Many church goers were shocked when restrictions allowed alcohol shops to remain open for customers but indoor church services, even with distancing and safety masks required, were prohibited. Another example was when the governor of one US state allowed gambling casinos to re-open at limited capacity before doing the same for churches.

Justice Alito of the U.S. Supreme Court commented insightfully that this pandemic has accelerated trends in society and created a real “stress test” for constitutional and human rights.

Secularization and the marginalization of religious belief and practice have been growing trends in many countries. I see the denial of the human right to religious liberty for many dying persons as a consequence of the increasing lack of respect and consideration for religious practice and belief.

What is frightening is the blindness to the pain and suffering being imposed unreasonably on patients and families. Empathy requires us to try and understand the feelings and beliefs of others. If what is being requested is impossible or clearly harmful, it can be refused. If a person values something tremendously, it should be given great weight. No one should be forced to cooperate with evil and violate their well-formed consciences, but what I see happening with the dying is a cold calculation. It is cheaper and easier to simply deny visitation and it can reduce the risk of contagion. That is enough justification for some.

Other factors and circumstances need to be considered when imposing restrictions that can force people to die without the comfort and assistance they desperately want and need.

I know that you recently faced a very serious health crisis which put you in the hospital, with a serious possibility that you might not survive. What was this experience like?

Yes, I had a V-tach cardiac episode. It sent me to the nearest hospital in an ambulance. If I had not been defibrillated and revived, I could have died. I am very grateful for the medical workers and technology that kept me alive. My wife played a key role in calling for help immediately after she noticed that I was unconscious and not asleep. Her vigilance prevented the possibility of simply dying in my sleep.

She followed the ambulance to the hospital and requested a priest to give me last rites as my life was clearly in danger. The secular hospital had a chaplain on duty who came, but she was Protestant and could not give me Catholic Anointing of the Sick. When I woke up in the intensive care unit the next day I also asked for a priest and was told that none could come. The hospital COVID policy prevented my wife from visiting or a priest from coming in from outside. They did have chaplains on staff who could visit me, but none was a Catholic priest.

I recovered quickly and was discharged after 4 days. Our parish priest had his request to come and confer the sacraments denied by the hospital. Father Rock anointed me the day after I was out of the hospital. The medical staff were friendly and treated me well, but the very restrictive policies of the hospital tied their hands and inflicted suffering on me and my family. I can’t imagine how bad it would have been if my condition had proved untreatable, and I was forced to die isolated from family and the sacraments.

What practical steps do you think hospitals and care homes should take to ensure this right to not die alone is respected, while at the same time protecting the wider society during the pandemic?

It seems to me a great deal can be done. Clearly, some restrictions make sense. Digital video calls and telephone calls can help ease the burden of isolation and should be facilitated. When a patient is in danger of death it is cruel to deny access to the closest family members and spiritual assistance.

Reasonable safety precautions can and should be required. It is not difficult to learn how to don and use PPE and to follow elementary safety rules. Priests cannot confer sacraments over the phone, but they can do it safely in person while wearing PPE. These kinds of accommodations are not unreasonable and would make a world of difference for patients and their families. I think what is needed is a greater understanding that spiritual and emotional care are essential when some persons are facing death and are as important or even more important in some cases as strictly physical medical assistance.

The National Catholic Bioethics Center maintains a free individual ethical consultation service. Thousands of people call or email us. People tell us of tragedies where elderly patients in care facilities lost the will to live when denied all personal contact with loved ones in recent months. They died as a result of policies meant to protect them that had the opposite effect. These real risks also need to be taken into account and understood. The way we respond to a crisis says a great deal about our priorities and compassion.

Follow Charles Collins on Twitter: @CharlesinRome