[Editor’s Note: Dr. Josh Packard is Executive Director of Springtide Research Institute and Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Northern Colorado, where he serves as executive director of the Social Research Lab. Josh is an accomplished researcher, speaker, and academic studying the sociology of religion and new forms of religious expression. He has written numerous articles and given dozens of speeches about religion in America. He is also author, with Ashleigh Hope, of Church Refugees: Sociologists reveal why people are DONE with church but not their faith (Group, 2015). He spoke to Charles Camosy.]

Camosy: There is lots of interest in the views of “young people” these days, especially with respect to their religious views, and especially – given the world Crux inhabits – in the Catholic Church. Much has been studied and said about these matters already, with special attention to the “nones” who don’t identify with institutional religion. Can you say something about why your study of young Catholics is different than what we’ve seen in recent years, especially with regard to its methodology?

Packard: Yes, the spiritual lives of young people and the rise of the religious “nones” has been a topic of significant interest for many people, and rightly so — any religious leader with stakes in their own institution and the well-being of this upcoming generation should be thinking about these questions of affiliation and disaffiliation.

Although the topic is well-covered in a certain sense, it’s often impossible to do anything about the data that’s been presented. But we at Springtide Research Institute don’t collect qualitative and quantitative data on the inner and outer lives of young people for shock value or catchy headlines. We listen to their stories so we can amplify their voices. We amplify their voices so the adults and leaders in their lives can learn how better to serve them.

In that sense, this study of young Catholics is considerably different. It’s data about the complexity about their religious identity, beliefs, and practices—and it’s a framework for how to build trust in light of these complexities. This commitment to the nuance of young people’s stories is reflected in our methodology. We surveyed over 10,000 young people aged 13-25 to get a nationally representative sample across gender, race, and region. We interviewed 165 young people and heard their stories in-depth to see how it matched, deepened, or complicated what our survey data revealed.

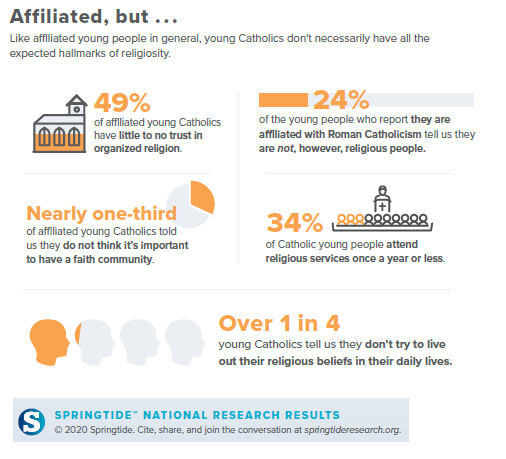

A quick note on the “nones,” though. The report we just released focuses on Catholic young people. But it’s important to note that religious affiliation simply doesn’t mean what lots of people might expect. A “none” might be attending worship within a committed community of like-minded individuals. A “Catholic” might go on nature walks on Sunday morning. Young people have an “unbundled” religious sensibility, meaning they are gathering up aspects of their religious lives from various sources, rather than one bundled up, complete source: their religious identity (i.e., Catholic) could come from one source, while their religious practices (prayer, worship, walks), or religious beliefs (God, the communion of saints, forgiveness) might come from another.

This is another difference between our study and others. Others investigating Gen Z and religion simply don’t go far enough to understand this group, which perpetuates the notion that “none” really means nothing. This results in an overly simplistic picture of a group that (of course!) has religious and spiritual impulses, but simply isn’t expressing these in ways that categories like “affiliated” and “unaffiliated” can detect or appreciate.

What were the most important takeaways from the study, in your view?

Our study confirmed that Gen Z is incredibly lonely. 40 percent told us they feel they have no one to talk to and that no one really knows them well, at least sometimes. Of young Catholics, 45 percent feel that no one understands them, while 65 percent have three or fewer meaningful interactions in a regular day. The pandemic only exacerbated this problem — across the entire sample, 60 percent of young people agreed they felt very isolated as shutdowns and social distancing began, while 44 percent agreed they were scared and didn’t want to be alone.

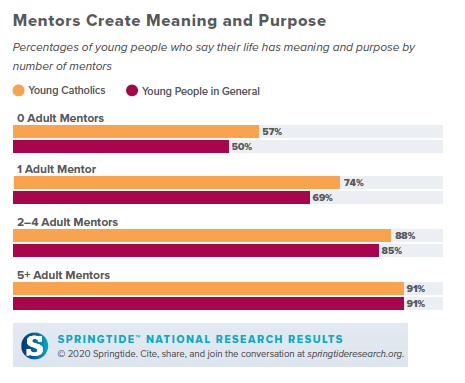

But there’s a clear (though maybe not always simple) solution. Our data make it clear that the presence of trusted adult mentors can have a significant impact; more mentors make young people less likely to say they experience isolation and loneliness, and more likely to say their life has meaning and purpose.

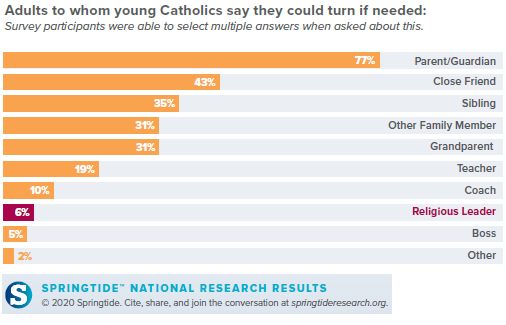

But these all-important trusted adult mentors are rarely religious leaders — just 8 percent of young people say there is a religious leader they can turn to if needed. This number is slightly lower for young Catholics – only 6 percent say they turn to a religious leader when in need. On the whole, just 1 percent say a religious leader checked in with them as shutdowns and social distancing began in Spring 2020.

These findings around mentors, meaning, and loneliness are critically important. But it can be hard to do something about this information. We developed a framework, derived from the data, that outlines what we heard from young people about building bonds of trust with adults in their lives. We call this framework Relational Authority. Those who rely on relational authority are best poised to be who young people need right now. Relational authority combines the sharing of wisdom and expertise with the practices of listening, transparency, integrity, and care. On the contrary is an approach that relies on one’s institutional authority to do the heavy lifting. What young people desire right now is to feel seen, heard, and related to. This requires leaders to invest themselves, and not just their programs or pedigree, into young people to earn their trust.

It is not just religious institutions that young people find difficult to trust right now — it’s all of America’s institutions, including schools, congress, and the media. In a society increasingly glued together by impersonal, transactional exchanges, young people have a deep need for connections that are familiar, honest, and long-suffering. Religious leaders of all faiths have an opportunity to meet that need, as well as parents, siblings, coaches, teachers, and even bosses.

My sense of the data from the past is that young people have tended to be pretty “secular” – for lack of a better word) – when compared to older people, for some time now. Are young people more secular today than young people were in the previous generation?

Whether young people are more “secular” today really depends on the questions you’re asking. For example, if you’re asking about the importance of organized religious institutions in their lives, then yes, young people today appear to be less religious than previous generations.

Half of young Catholics today, for example, report little to no trust in organized religion. A third of young Catholics told us they do not think it’s important to have a faith community, and a third attend religious services once a year or less. Like their peers, a sizable chunk of young Catholics doesn’t necessarily consider institutional engagement to be an important aspect of their faith.

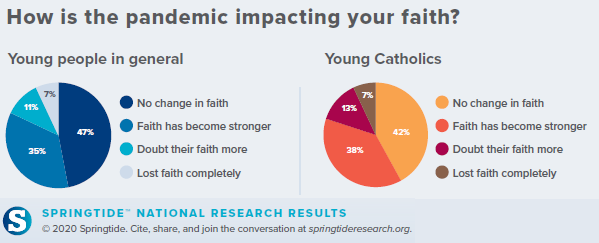

However, this is just one way to draw it up. We also discovered that a greater proportion of young Catholics have become more religious (37 percent) than less religious (24 percent) in the past five years, while more young Catholics have grown in their faith during the pandemic (38 percent) than those who have doubted more (13 percent) or lost their faith completely (7 percent). Nearly seven in 10 young Catholics (68 percent) say that religion shapes their daily life, and a whopping 91 percent consider themselves to be at least slightly religious. These trends have to count for something, right?

There’s a temptation (among sociologists, especially!) to compare generations. If young people don’t worship the way others have, approach religious institutions the way others have, or maintain the same religious practices others have, this is often met with handwringing, or perceived by some as a threat to faith in America. There’s implicit pressure placed on young people to change the way they seek the sacred in order to maintain the institutions that are already built.

Springtide isn’t a religious organization, but we are in the business of helping all kinds of organizations be more effective in the ways they relate to and understand young people. By all means, we want organizations to succeed—and we want young people to flourish, too. So we tend to think the handwringing is in vain: start with listening and meeting them where they’re at. Young people need guides and trusted mentors as they navigate life’s biggest questions, but they tend to be skeptical of anyone who begins with a rigid agenda.

Was a young person from my generation (Gen X) who was dragged to Church against his will by religious parents, and wrote down “Catholic” on a survey or college application, necessarily more religious than someone today with secular parents who doesn’t take them to Church and doesn’t write down “Catholic” on a survey?

I can imagine both kids having very similar beliefs but being counted differently. This question is related to a thesis Ross Douthat has about disaffiliation in general: Namely, that people who are formally disaffiliating today don’t have religious and ethical beliefs that are all that different from folks of the previous generation, but people of a previous generations had cultural and familial reasons for identifying with institutional religion that don’t exist as strongly today, at least in Western consumerist countries like the United States. Any reactions to any of this?

One thing is for sure: Young people’s beliefs, behaviors, and survey responses (as you mentioned) didn’t arise in a vacuum. They are subject to larger cultural shifts that impact the way every living generation makes meaning, builds community, or experiences trust. But I do think you’re right that affiliation or disaffiliation, as terms for accurately reflecting a person’s beliefs or sense of belonging within an institution, are insufficient—and maybe have been for a long time. That’s one of the main theses of our State of Religion & Young People 2020 report, in fact.

Like generations of young people before them, young people today are trying their best to navigate questions of identity, community, and meaning, and our research shows that they are doing so without much help from religious leaders. In some sense, this generation may just be more honest or articulate than previous generations in describing where they are in their relationship to or affiliation with a specific religious tradition.

What, if anything, did you find about the effect of Donald Trump on young people in this area? I can imagine some young people (wrongly, but perhaps understandably) identifying Catholicism with MAGA and being turned off for that reason.

While we cannot attribute their political impressions explicitly to the actions of any specific political leader, we did discover that young people, Catholics included, are feeling alienated by the political climate in America today. When asked how they find adults in general when they talk about politics, young people selected aggressive, dismissive, and disengaged (65 percent) almost twice as often as they selected considerate and inviting (35 percent). Forty-one percent of young people in general, and 50 percent of Catholic young people, feel that most adults in their lives disregard their feelings about political issues.

Young adults, we discovered, are pining for a more empathetic and understanding brand of politics. Sixty-eight percent of the young people Springtide surveyed say that they would not stop speaking to someone who strongly disagreed or opposed their political values, and 77 percent want to be having conversations about differences openly. Eighty-one percent of young people say it is important to try to understand both sides of a political issue, and 84 percent of young people agree that getting educated about the views and perspectives of others is important for seeing both sides more clearly.

Young Catholics seem to be especially eager to conversate around politics. Six in ten young Catholics say they know more about politics than adults give them credit for. They’re also conscious of how their faith and their politics intersect: 77 percent agree their faith affects their political involvement at least a little. However, the majority (52 percent) say that faith leaders have no impact on their politics whatsoever. While faith may be informing their politics, for many young Catholics, faith leaders are perceived as uninvolved.

Of course, then there’s the “what is to be done?” question for those of us who love the Church and believe it is existentially important, especially for young people. On the one hand, there’s the obvious response to try to adjust the Church’s approach on the things which are leading people to disaffiliate. But this is complex because it is often those very teachings and practices which keep so many millions of people still with the Church. It is difficult to know how to respond.

This tension is difficult, at times even paralyzing when trying to determine what can or should be done. Many religious leaders sought their roles precisely because they had formative, positive experiences within that institution—and understandably, they want to pass that kind on the next generation of young people. It’s a double-edged sword: fear of watering down teachings to be relevant or doubling down on difficult teachings to draw a line in the sand, relevance be damned. But can’t institutions have both? We hear this kind of question all the time.

We’re not advising any institutions to give up core tenets. Our data suggests the most important thing is relationships. For many in the church, this may be much harder than either of the two edges of the sword, because it means maintaining relationships – maintaining a consistent presence – as a young person navigates life’s biggest questions. These questions may lead them toward or away from a particular tradition. But the presence of even one trusted adult within an organization will help them feel like they belong.

Taken together, our findings show that young Catholics need to feel cared for before they can be receptive to the influence or authority of others in their lives. Consider these findings:

— 85 percent of young Catholics say they are more likely to take advice from someone who cares about them.

— 69 percent of young Catholics agree with the statement: “A person’s expertise doesn’t matter if they don’t care about me.”

— 82 percent of young Catholics say they will trust someone who takes the time to hear what they have to say.

— 77 percent of young Catholics say they feel listened to when people show they understand what they’ve been through.

Put simply, relationships of care are what young people desperately need and desire right now. Young people are plagued with experiences of loneliness and purposeless, and trusted adults have an opportunity to turn the tide. Leading with a rigid agenda, an “in or out” mentality while they’re navigating big questions, won’t ultimately serve them or your institution. When adults care for, listen to, and guide young people, they thrive. When the time is right, check in with the young people in your life, and don’t underestimate the impact you will have when caring for them.