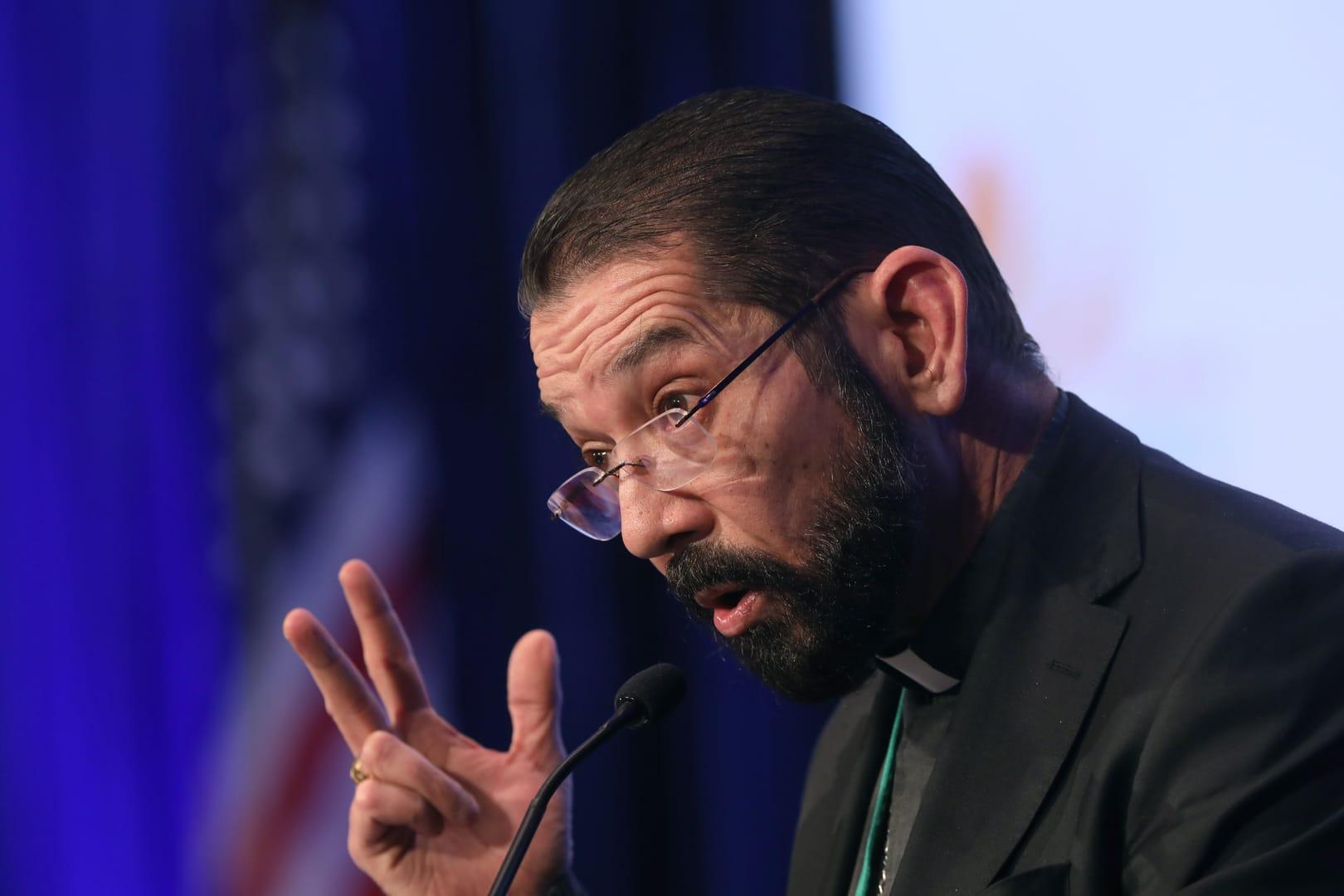

BALTIMORE — According to Bishop Daniel Flores of Brownsville, Texas, the Catholic Church has to have an independent voice to speak up when they agree or disagree with the government, and it shouldn’t “shouldn’t be captive to one party or another.”

Flores became the head of the doctrine committee of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops the moment their fall general assembly concluded Wednesday night, and had been tasked with coordinating the preparation of the synodal process launched by Pope Francis in October.

Each diocese is called to have a synodal consultation, that will then be analyzed at a national level, a continental level, and eventually, in the Vatican, with a meeting of the Synod of Bishops in Oct. 2023.

Crux spoke with Flores about the synodal process in the United States.

Crux: How interested or committed do you sense the bishops are in the synodal process?

Flores: I think there is strong interest. I’ve noticed that in some dioceses they have already moved this forward, and there are probably some bishops who are still kind of trying to figure out how to do this with the resources that they have. I think the interest in it is growing as they understand it more.

Part of what we have to do is help our people understand what a synodal time looks like, and invite them to participate. I will say this: culturally in the United States, we have a problem. It’s not so easy. We like to see what’s the structure, and what’s the outcome we want: We want everything already written.

And in the synodal way, which is theologically an ecclesial way, the body of the church doesn’t work necessarily that way. It’s an opening, it’s listening, it’s prayer, it’s adoration. It’s then seeing what you gather and then you just kind of take it step by step.

That’s one of the questions I’ve gotten the most from the dioceses: The lay leadership wants to know what’s going to be the outcome. At the end? We’ll see what’s there! Which I think is the answer the Holy Father would give: at the end we see what’s there.

It’s a valid question though, the one they are posing…

Oh, yes, absolutely. But let’s do the first thing first: Let’s listen to each other, let’s pray, and then see where this takes us. One of the things I’ve been trying to convey in my diocese, is that this is meant to strengthen our community, to listen to each other, for the sake of making us better as people doing the mission, and the pope is very clear about what the mission is.

I think the bishops are more and more especially now that we’re kind of coming out of the COVID situation.

And also moving on from the document on the Eucharist…

Yes, though that wasn’t as important as people think it was, it wasn’t as bishops were thinking about it every day. I mean, the draft went out and amendments came in and you got a sense that we were coming together with it, producing a document the bishops were comfortable with.

But there’s been a lot of other stuff that the guys have been worried about.

Coming into the meeting this time, there were a lot of rumors or reports of bishops who were trying to modify the document on the Eucharist, trying to make it more explicit, or less.

It’s not unusual. I mean, certainly we got amendments, from all sorts of different perspectives, and all those amendments come to the committee and the committee and as you saw this morning, we decide which ones we want to accept or not. And this is made knowing full well that anybody could get up and say “I would like a vote on that amendment.”

As a member of the committee, I was pleasantly surprised that there was discussion, but there seemed to be a basic sense that we had hit the right tone that we could agree on as a body of bishops. The pope tells us that we must have a lot of dialogue, and sometimes rough conversations, because we can be passionate about things. But with time- time is more important than space- we achieved a sense of calm.

Were you surprised when the discussion came, there were very few people standing up?

Well, you never know, because each one… But I thought we had talked through in the amendment process what the body of bishops seemed to be thinking about. Even in the proposed changes this morning, the body didn’t seem that interested in changing the text as it is. I think they felt that we had hit the right tone and content, and some of that stuff was very carefully crafted. In terms of what you can say.

Are you planning on presenting the document to the Vatican? Because if so, it will be up to you, as the new head of the Doctrine Committee.

I have to check on that. My hunch is no: There’s nothing new in the document. I’m not a canon lawyer, but I think there’s nothing doctrinally innovative in the text. It’s a doctrinal statement. But if we do, we’ll send it. But I don’t think it requires a recognizio. But it would have to be me presenting it, as I take over when this meeting is over.

How do you feel about that?

It’s more work, but that’s okay. The committee does good work. It’s a hard working committee, because aside from all these things that kind of make the headlines, there’s a lot of consulting from bishops who ask different questions.

Since a lot of your work is connected to migrants, do you feel that you dodged a bullet with the document not naming [President Joe] Biden, not fully rocking the boat with the administration? Or is it just understood that you’re gonna clash in some things?

I think that’s kind of the modus, and this was true also under the previous administration, I felt that we needed to say when we were opposed to what they were doing on the border. The church has to have an independent voice to say we agree when we can agree, and when we can’t agree we’re going to say something. And that’s the way it works. I mean, the church is free to speak, and we shouldn’t be captive to one party or another.

I think that document made a special sort of effort to say that, the issue of any leader, whether it’s a politician or a movie star, or what they call an influencer, it’s the responsibility of the local bishop to address the question of the Eucharist. And that’s a dialogue between the faithful and the pastor.

Going back to the Synod. Some dioceses have websites launched and are already doing things, and other dioceses are struggling to find people to even build a team. As this process unfolds, how do you make sure those smaller dioceses or even just dioceses in general that fall behind, also get heard?

You want to encourage and I think one of the things is finding a way to encourage them. My diocese is not small in terms of people, but the resources are fairly limited. And I just find that people are responsive, and you can get people together. And you have leadership. I mean, lay leadership is the key, because they’re there and they are capable of then pulling in other people. It doesn’t need to take a lot of money, but a focus of the lay leadership, and we need to train people on how to listen, because it’s not a natural thing for us.

I also think the larger archdioceses have a different kind of an obstacle: The larger archdioceses who are that are extremely well organized, sometimes have a hard time sort of adapting to this different way of organizing a camino. And so there’s problems there too. So I think we have to help each other. I think that’s part of what we want to kind of communicate with this. You know, we need to share the resources and we’re willing to talk to each other.

And what’s unique, do you think, about the synod process in a border diocese?

That’s a very good question and we’ve put some thought into that: I’ve already been talking to Sister Norma Pimentel. We need to get the consultative process into the migrants we just have with us overnight, to get their sense as to what they’ve gone through and what they need.

And also in the colonias, which are the peripheral areas. And Bishop Eugenio Andrés Lira Rugarcía of Matamoros and I have already been in conversation about doing a joint consultation, because we have a lot of families who have part of their life on the Brownsville side and part of their life in Matamoros. Their experience of the church is that they work on this side during the week, but then they take the children to their grandparents over the weekend, and they go to Mass and catechism school over there, and then they come back.

We want to try to capture their sense of the church attending to them in this both sides world because we make a conscious effort to do that. For example, we try to make it as easy as possible for people to baptize their kids: if they’re prepared in Matamoros, they can be baptized in Brownsville.

We want to try to capture that border experience of living the life of the church in two different dioceses, because the people are one same church. And at least before COVID, they saw me there enough, and we have bishop Lira enough, that we all know each other. But we do want to capture the experience of having a church between international borders, with families living on both sides.

In COVID it was very hard because we have people whose family members were dying and they perhaps struggled to get across, or they couldn’t get into the hospital. So they were saying goodbye over the phone. It was heartbreaking.

Follow Inés San Martín on Twitter: @inesanma

Follow John Lavenburg on Twitter: @johnlavenburg