“Stations of the Cross” is streaming via Netflix and available on DVD or Blu-Ray or for rent or purchase via Amazon Video.

Dietrich Brüggemann’s “Stations of the Cross” opens with a catechism class, a small group of confirmation candidates being instructed by a young priest (Florian Stetter). The writing is so sharp and precise, it could almost be a scene from a documentary; the priest comes across as lucid and even inspiring, despite some troubling rigidity.

He speaks of the love of God growing in their hearts, of the flame of faith growing into a large fire to illuminate a dark world, of the battlefield in the heart between good and evil, of the universal brotherhood of all mankind. He also warns them, in broad, unnuanced strokes, about vanity over one’s appearance and satanic popular music.

Urging them to be witnesses to their peers, he seems less concerned with, say, befriending outcasts or doing good to those who mistreat us than with the impurity of provocative clothing and teen magazines.

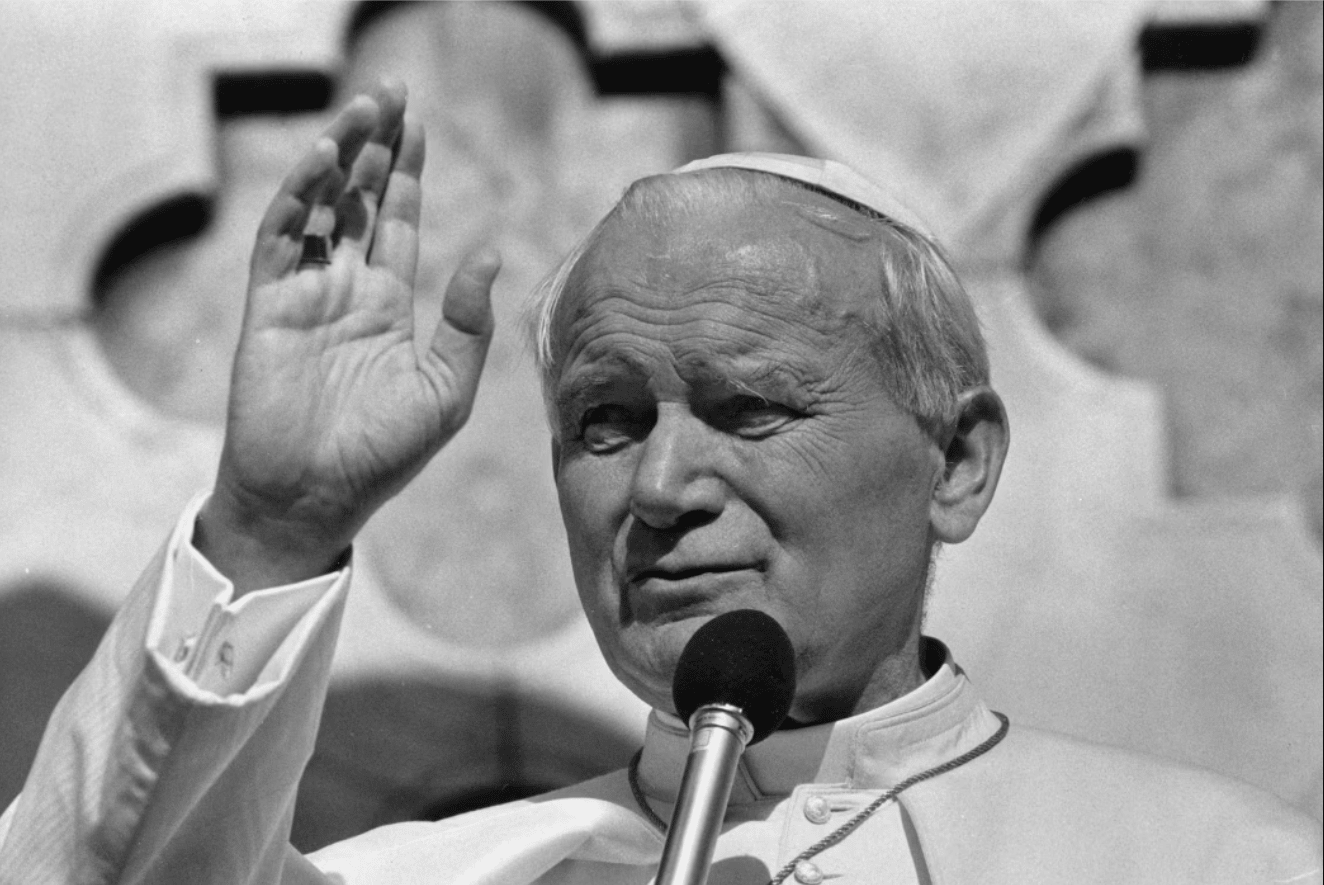

The blend of genuine spirituality and priggishness is queasily persuasive, and hardly less unsettling when it comes out the priest and his little flock belong to a splinter traditionalist group — a thinly fictionalized version of the Lefebvrites or Society of St. Pius X — that rejects Vatican II and sacrilegious novelties such as Communion in the hand and Mass with the priest celebrating versus populum (facing the people). (The screenplay, cowritten by the director and his sister Anna Brüggemann, shows a clear familiarity with this stripe of Catholic traditionalism.)

Then comes the twist of the knife. After class is over and the other children have left, the priest’s star pupil, a well-catechized girl named Maria — brilliantly played by newcomer Lea van Acken — questions the priest along lines that, to a savvy adult, would be a flashing warning sign. In this world, though, all is spirituality and theology; psychology and emotions barely register.

By the scene’s end, it is all too evident why this opening scene, shot in a single 15-minute static take, has been titled “1. Jesus is condemned to die.” We can guess what will follow: 13 more shots, all filmed with a camera that is as immobile as the ideology of Maria’s world, bearing the titles “2. Jesus carries his cross,” “3. Jesus falls for the first time,” and so forth, ending with “14. Jesus is laid in the tomb.” Will there be any hope or hint of redemption in this contemporary passion play?

“Stations of the Cross” is among the most insightful and devastating cross-examinations of religious fundamentalism that I have ever seen, certainly in a Catholic context. The film is not an attack on faith or religion, but rather an examination of how faith goes wrong.

What is it that makes this religious subculture toxic? The general shape of their dogmatic beliefs is not so different from mainstream Catholicism. Their belief that the gates of hell have prevailed against the Church and that only in their splinter group is the true Faith preserved is troubling, but not the whole problem; similar cultural problems can be found in conservative Catholic communities in full communion with Rome, as well as Orthodox and Protestant communities.

One way of putting it would be to say that this sort of fundamentalist or traditionalist worldview (NB: not all forms of fundamentalism or traditionalism) offers a totalizing account of life, the universe, and everything.

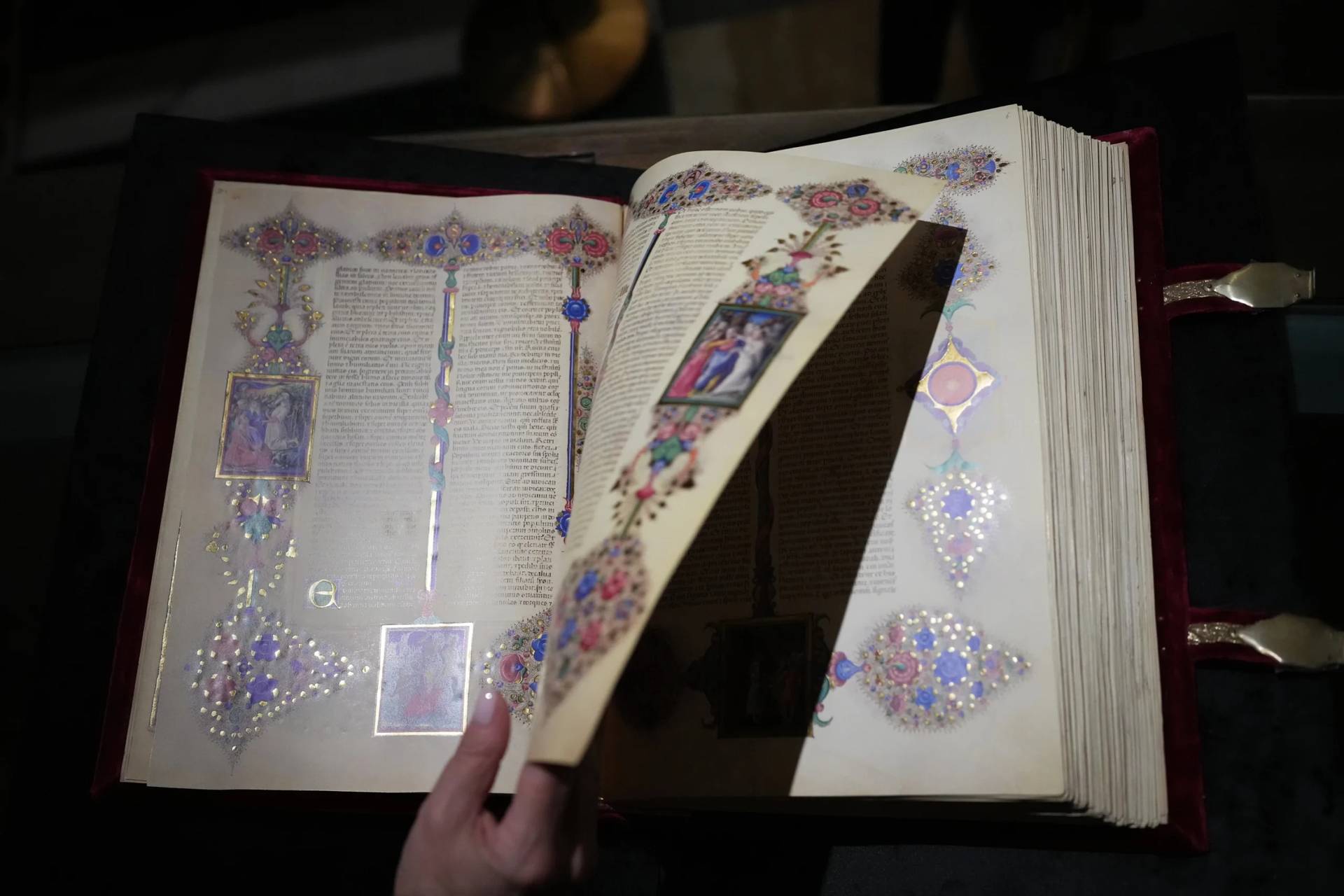

All the answers are set forth, clearly and unambiguously, in the catechism (not, of course, the post-Vatican II Catechism of the Catholic Church, but the post-Tridentine Roman Catechism, along with the Summa, the writings of the saints and spiritual writers of the past, etc.). The priest, the theologian, and the faithful have nothing to learn or to gain from the scientist, the psychologist, the physician (or nurse), the philosopher, the poet, the pop musician, or the filmmaker (much less the film critic).

One could also say that the fundamentalist worldview offers a binary outlook on the world in terms of sacred or profane, with everything on the profane side of human experience under a cloud of suspicion. More particularly, modernity is viewed with deep jaundice; traditionalism, like many conservative ideologies, embraces a narrative of decline, with a golden age sometime in the past and the sky always falling in the present.

Also under suspicion is simple pleasure, whether at the sight of a beautiful landscape or at attention from a peer of the opposite sex. In all these things the enemy lurks, ready to pounce and devour. Sexuality, particularly female sexuality, is practically ground zero for the powers of darkness; jewelry, makeup, hairdos, and so forth are all snares and temptations.

Looming over the stifling tableaux of Maria’s life is the domineering figure of her mother (Franziska Weisz), a bitter, brittle woman with a prickly temperament and an acid tongue. I wish it were true to say that her character is too one-sidedly harsh. We do get glimpses of her humanity, as when she tries to make up for berating Maria by offering to take her shopping for a Communion dress, and assuring her, as if by concession, that it’s okay to wear something pretty for this special day. The smile on Maria’s face at this rare show of maternal warmth may be the film’s heartbreaking moment.

Contrasting with her mother is Maria’s French au pair Bernadette (Lucie Aron), idealized in Maria’s eyes as the epitome of virtue, cleverness, and beauty. In Bernadette’s unconditional love, Maria finds solace from her mother’s coldness.

People from outside Maria’s world drift through key moments in her life, living signs of hope. There’s the Protestant gym teacher (Birge Schade), who responds with tolerant empathy to Maria’s objections to the driving beat of the Swedish pop duo Roxette’s “She’s Got the Look,” and defends her from jeering classmates. There’s Christian (Moritz Knapp), a boy at school who likes both Bach and rock and resists all Maria’s efforts to discourage him from pursuing her.

The typological links between the film’s 14 unbroken shots and the stations of the Way of the Cross are not always exact; as with the 10 episodes of Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Decalogue, though to a lesser degree, it is sometimes possible to doubt the exact thematic connections. Brüggemann’s formal rigor bends only twice, with camera movements limited to two key shots (not counting a conversation in a moving car). The first set of camera movements heightens the significance of the scene; the second allows us to see, if we wish, the presence of grace in Maria’s sad story.

The French Catholic writer Léon Bloy once proclaimed, “The only real sadness, the only real failure, the only great tragedy in life, is not to become a saint.” There is great truth in this dictum, though after watching “Stations of the Cross,” I fear I can only half agree.

Is Maria a saint? I think perhaps she is, yes. Even so, her story remains a tragic one. Not to be a saint may be the greatest sadness, the greatest failure, the greatest tragedy — but it is not the only one.