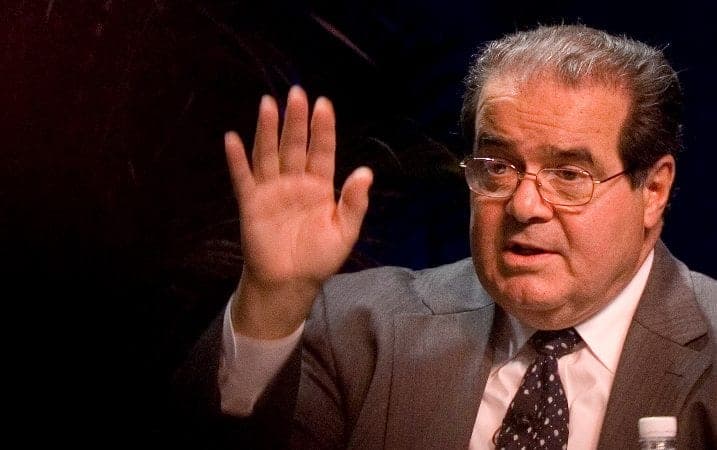

In a moment when so many who actually knew Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia are offering tributes, it seems superfluous for someone who only met the man once, and whose perceptions are formed almost entirely by his public record, to join the chorus.

Nonetheless, I do so because there’s a point about Scalia that risks being lost amid the avalanche of reflections on his legal and political legacy, and which my own tiny sliver of experience can certainly confirm: Scalia was a deeply engaged Catholic, whose faith was one of the cornerstones of his life.

This is a man, after all, who attended Xavier High School in Manhattan and Georgetown University in Washington, who has a son who’s a Catholic priest, and who publicly acknowledged St. Thomas More as a hero.

His overt loyalty to Catholicism, coupled with his conservative legal reputation, made him a magnet for all manner of whispering over the years. When I published a book on Opus Dei in 2004, for instance, one of the rumors I was compelled to run down was whether either Scalia or Louis Freeh, the FBI director from 1993 to 2001, was a member of the conservative Catholic group. (For the record, neither man was.)

My one bit of personal contact with Scalia came in 2012, when we had both been asked to be keynote speakers at a conference in the Archdiocese of Denver called “Living the Catholic Faith.”

(As a footnote, there were three keynoters: Scalia, myself, and Brother Guy Consolmagno of the Vatican Observatory. Organizers conducted an on-line poll beforehand asking participants who they were looking forward to hearing; Scalia won in a landslide, Consolmagno came in second, and I finished a dismally negligible third.)

My wife and I were invited to a dinner during the conference for speakers and guests, and we ended up seated at the same table with Scalia and his son, Paul, who’s a Catholic priest.

I was startled to discover that Scalia knew who I was, and he proceeded to spend much of the evening grilling me about Vatican politics and Rome’s attitudes toward the world. It was clear from the tenor of the conversation that he was fascinated by Catholicism generally, and the papacy in particular.

Knowing that Supreme Court justices aren’t supposed to discuss legal questions that are either currently before them, or which might reach them some day, I didn’t quite know how to ask the questions I was interested in, such as his attitude about the contraception mandates imposed by the Obama administration as part of health care reform.

I was surprised, therefore, when Scalia raised the issue himself, asking me if I thought the US bishops were planning to take their fight against those mandates “all the way.”

I said I suspected they would, which led Scalia to ruminate on what might happen if a case testing the mandates reached the court.

I wasn’t taking notes, but what he said was something like the following: “If the bishops want an exception from the law, they should try to get it through the democratic process … Americans are very generous about accommodating religious beliefs … rather than trying to get it from the courts.”

That may have been a reflection of the position Scalia took in the 1990 Employment Division v. Smith case, involving a state employee denied benefits for violating a drug policy, despite the fact that the drug in question, peyote, was part of a religious ritual. Scalia held then that while states have the power to accommodate religious beliefs, they’re not required to do so.

Of course, Scalia later sided with the majority in 2014 in striking down the mandates as they applied to closely held for-profit corporations in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores Inc., but now we’ll never know how he might have ruled in the Little Sisters of the Poor case, which the court has agreed to hear.

Quite aside from his legal views, what came through that night four years ago was just how keenly interested Scalia was in Church affairs, and how central reflection on his faith was to his life and his worldview.

There are, of course, Catholics who don’t believe Scalia drew the correct conclusions from his religious convictions, seeing his “originalist” view of the Constitution as more about conservative political ideology than genuinely Catholic sensibilities.

What can’t be denied is that Antonin Scalia was a serious Catholic, someone whose faith was a defining element of his life. His passing is a reminder that Catholicism’s contribution to public life in the United States may not always be ideologically coherent or predictable, but it’s profound, and he was a lifelong embodiment of that truth.