ROME – Every culture tends to develop its own peculiar obsessions with conspiracy theories. To this day, for instance, a great way to get three or four Americans arguing is to ask their opinions about whether Oswald acted alone in the JFK assassination.

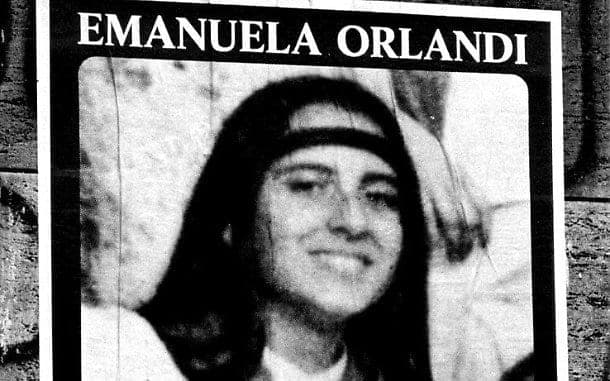

The rest of the world, however, really doesn’t hold a candle to Italy when it comes to generating what are known here as gialli, basically meaning unresolved mysteries. One of the most popular for almost the last 35 years has focused on Emanuela Orlandi, the 15-year-old daughter of an employee of the Vatican bank who disappeared in 1983, and whose fate has never been established.

Over the years, various theories have been floated: Orlandi was kidnapped by radicals seeking to pressure St. Pope John Paul II to liberate Mehmet Ali Ağca, who had tried to assassinate the pontiff in 1981 and who was being held in an Italian prison; Orlandi was taken by elements of the Italian mafia, trying to force the Vatican bank to pay back mob money lost in the scandals of the 1970s and 80s. That idea flared up again when a famed mob boss named Enrico De Pedis was buried in the Roman basilica of Sant’Appollinare, located in the same piazza where Orlandi went to music school, and some even wondered if Emanuela was entombed with him (or instead of him) and demanded an exhumation.

(That happened in 2012, when police investigators found only the remains of one adult male in the tomb.)

There’s even the hypothesis that Orlandi was swept up and kept hidden away by a Vatican sex ring. That reconstruction was advanced in 2012 by Don Gabriele Amorth, the famous Roman exorcist, who died in 2016.

Thus it was perhaps inevitable that on Monday, an Italian journalist named Emiliano Fittipaldi, already well-known as one of the reporters involved in the “Vatileaks 2.0” scandal involving stolen records related to Vatican finances, would roll out yet another supposed blockbuster in the Orlandi case.

Specifically, Fittipaldi published a portion of his new book devoted to a purportedly secret document outlining a half-billion Italian lira (roughly the equivalent of $300,000) the Vatican is supposed to have spent on keeping Orlandi hidden between 1983 and 1997, when no one theoretically knew where she was, including costs for a residence in London and occasional medical expenses, plus investigations and “throwing things off track.”

The memorandum supposedly was written by Italian Cardinal Lorenzo Antonetti, at the time the head of the Administration of the Patrimony of the Apostolic See (APSA), and addressed to now-cardinals Gianbattista Re and Jean-Louis Tauran, both at the time senior officials in the Vatican’s Secretariat of State.

On Monday, Re denied ever having seen the letter or any summary of Vatican expenses on Orlandi, and Vatican spokesman Greg Burke told journalists the report is “false and ridiculous.”

Also, later on Thursday, the Vatican released a more formal statement, saying that “the Secretariat of State firmly denies [the authenticity] of the document, and declares completely false and without any foundation the news it’s supposed to contain.”

“Above all, it’s regretful that these false publications, which damage the honor of the Holy See, [also] deepen the immense sadness of the Orlandi family, with which the Holy See repeats its solidarity,” the statement said.

From the beginning of his piece in the Italian newspaper La Repubblica, Fittipaldi makes clear he has no way of knowing if the, memo is authentic. It’s written on plain white paper with what appears to have been an old typewriter, with no Vatican letterhead and no official protocol number, and although Antonetti’s name appears at the end as the sender, there’s no signature. Fittipaldi says that it was passed to him in a coffee bar in the center of Rome by a Vatican insider in an official-looking folder.

Basically, Fittipaldi presents his readers with a choice. Either the document is genuine, he says, in which case it raises explosive questions about what the Vatican is hiding, or it’s a fake, which, he asserts, would make it a sign of “unprecedented” power struggles inside the pontificate of Pope Francis, since Fittipaldi asserts it must have been prepared by an insider with intimate knowledge of Vatican procedures.

(Frankly, that strikes me as a dubious claim. If I wanted to, I’m pretty sure I could sit down right now and bang out an alleged Vatican document that would pass anybody’s initial smell test, though I’m not sure why I would.)

Fittipaldi doesn’t really speculate about what ends might be served by such a maneuver – except, perhaps, general destabilization.

Assuming the document remains impossible to confirm, it should be said that such exercises are nothing new in Italian affairs. A number of years ago, for instance, the editor of the official newspaper of the Italian bishops’ conference was fired when a fake police record made the rounds purporting to show he was under investigation for alleged harassment in a same-sex affair. (After the dust settled, he was appointed to a new position running the bishops’ TV network.)

Assuming this is another fake, there are lots of ways to explain the document’s provenance that don’t implicate anyone in the Vatican. For instance, the Orlandi family and their supporters long have insisted the Vatican knows more than it’s saying, and it’s possible someone in that world felt planting a false rundown of expenses might force its hand to come clean.

In the meantime, there’s another question to be asked, which is about the journalistic ethics of publishing something so obviously explosive without knowing whether it’s real — and, in this case, having pretty solid grounds for suspecting it might not be. (Among other things, Tauran’s first name is misspelled in the address line of the alleged memo.)

To be fair, Fittipaldi didn’t play games with his readers, acknowledging up-front he has no idea. Yet it’s still legitimate to wonder whether the more responsible move for a reporter, in such a case, would have been to wait before putting the document into circulation – where some, no doubt, will regard it as gospel truth no matter what anyone says.

The situation illustrates a chronic problem with Vatican coverage, which is that the tone typically is set by Italian media outlets, which seem to have a tremendous appetite for unresolved mysteries that play out over years, even decades. A package on one of the country’s main TV news channels Tuesday morning ended by saying, “It seems the Orlandi case is destined to accumulate more chapters,” and it’s hard to escape the impression that’s exactly how some people here like it.

In the midst of a situation where so much seems fuzzy, there’s at least one certainty: If this memo is indeed a hoax, someone clearly has too much time on his or her hands. It would be fascinating to know what motives would drive someone to manufacture such a thing – if it’s not, that is, just a case of ars gratia artis, meaning, more or less, for the simple heck of it.