Fans of Vatican-themed intrigue undoubtedly would say that the Belgian cardinal with the greatest direct influence on Pope Francis has to be Godfried Danneels of Brussels, a member of the so-called “St. Gallen Group” of left-leaning Princes of the Church who, reportedly, tried to block the election of Benedict XVI in 2005, and remnants of which later allegedly helped propel Francis to the papacy.

More sober observers, however, probably would insist that the real answer actually is Belgian Cardinal Joseph Leo Cardijn, the famed pioneer of the “See-Judge-Act” method in applying Catholic social teaching, the 51st anniversary of whose death falls today.

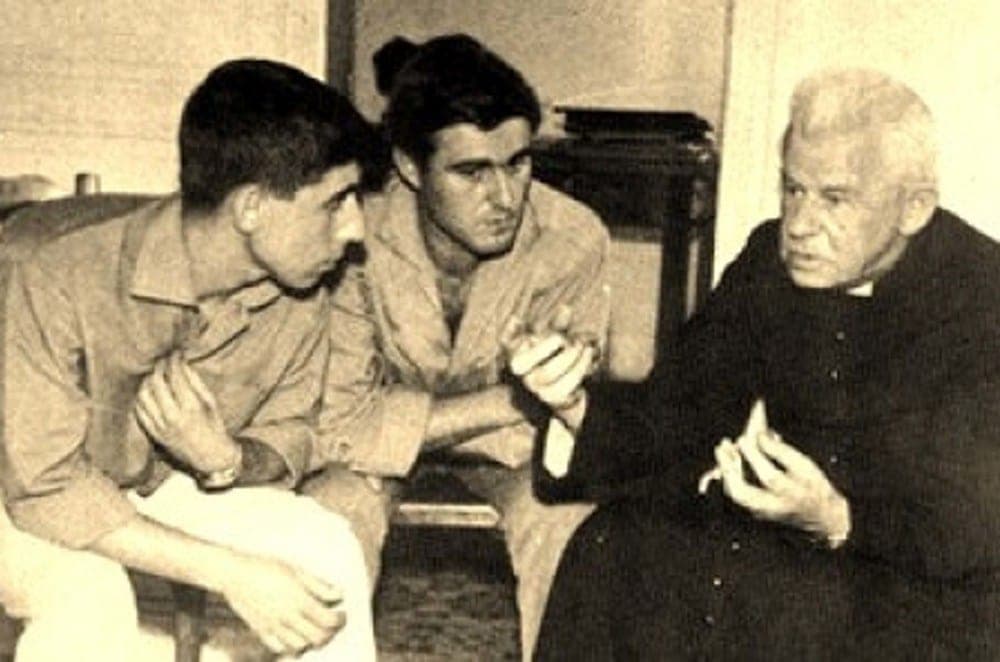

The bond between Francis and Cardijn runs, in part, through St. Alberto Hurtado, a revered Chilean Jesuit deeply familiar to the future pope, since then-Father Jorge Mario Bergoglio spent a year in 1960 living in the same house of studies outside Santiago where Hurtado lived and worked for much of his career.

Looking back over Catholic history over the last 135 years since Cardijn’s birth in 1882, it’s easy to connect the dots between his legacy and the agenda of history’s first Argentine pope.

Cardjin was born into a working-class family. His parents initially were superintendents for a block of apartments, and then his father became a low-level coal merchant while his mother worked at a café. Later he’d recall seeing workers file into local factories with their children, as young as 7 or 8, working 12-14 hour shifts with no rest breaks for a penny a day, with the children often locked in small rooms or tied to work stations so they couldn’t wander around the factory floor.

The young Cardijn decided he wanted to be a priest, and happily entered the minor seminary in 1897. When he came home on vacation for the first time, however, he was stunned to find that his former friends gave him a distinctly frosty reception – believing that by joining the Church, Cardijn had sided against them.

In 1903, when his father died, Cardijn vowed to spend his life serving the working class. By 1925, what would become his “Young Christian Workers” movement was off to a strong, yet controversial, enough start that he secured an audience with Pope Pius XI, who wrapped it in a warm embrace.

“Here at last is someone who comes to speak to me about the masses! The greatest scandal of the 19th century was the loss of the workers to the Church. The Church needs the workers, and the workers need the Church,” the pontiff said.

“Not only do we bless your movement, we make it our own,” Pius added, to be sure no one missed the point.

Two cornerstones of Cardijn’s vision, which would be picked up in Latin America both through the “base communities” movement and in the teaching of the Episcopal Conference of Latin America (CELAM), seem to resonate especially well with Francis.

The first is his famed “See-Judge-Act” method for discerning pastoral priorities, meaning to look around at the social reality, reach conclusions about what the Gospel has to say about it, and then put those conclusions into practice.

It’s effectively an inductive, rather than deductive, approach, one that begins not with doctrinal a prioris but clear-eyed observations about what’s happening in the concrete here-and-now. It was ratified explicitly by St. Pope John XXIII in his 1961 encyclical Mater et Magistra, a document for which the pontiff had asked Cardijn to serve as a primary contributor.

For Francis, who constantly warns of the dangers of intellectual “rigidity” and being cut off from the lives of ordinary people, the appeal is obvious – which is undoubtedly why “See-Judge-Act” is the basic structure of the 2007 Aparecida document of the Latin American bishops, of which then-Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio was a primary drafter.

The second pillar of Cardijn’s thought involves the primacy of the laity in terms of evangelizing the working classes.

As a young pastor, Cardijn had been assigned to the Royal Parish of Laeken in Brussels, located close to the palace of the King and Queen. At the time, the area also was home to 13,000 underpaid and overstressed factory workers. Cardijn tried to accompany them on the factory floor, but he was dismayed to find signs reading “workers only.”

In a very literal sense, he realized, if the Gospel was to be brought to the factory, it would have to be the workers themselves who did it.

That instinct, too, clearly tracks with the outlook of Francis, who has repeatedly called for greater lay empowerment in Catholicism, especially concerning women. (It’s worth noting, by the way, that the original group of workers Cardijn organized were young female needle-sewers, probably reflecting an intuition that women were especially vulnerable in a male-dominated economy.)

Despite the fact that Cardijn generated some blowback over the years, with critics accusing him of being a crypto-Communist and relativizing the faith in favor of some malleable social consensus, he enjoyed strong backing from the popes of his era.

In 1950, for instance, Pope Pius XII named Cardijn a “Privy Chamberlain of His Holiness,” allowing him to use the title “monsignor.” In 1965, just two years ahead of his death on July 24, 1967, Pope Paul VI named Cardijn a cardinal.

Granted, one can’t draw a straight line between Cardijn’s legacy and Francis’s papacy – history is too complicated for that, and there are too many intermediary points along the way between a 20th century Belgian prelate and the 21st century’s first pope from the developing world.

Still, the Cardijn story is a reminder that neither did Francis fall out of a clear blue sky. More realistically, his papacy can be seen as the confluence of a series of energies and impulses that have been building in Catholicism for more than a century – contested and, at times, choked back, for sure, but also never fully arrested.