(While the Italian bishops, gathering Nov. 10-13 for an extraordinary assembly, will receive the new guidelines on sexual abuse, a vote on their approval will not take place until an undisclosed date and the guidelines will notbe made public.)

DENVER – Two potential turning points loom this week in the Catholic Church’s fight against clerical sexual abuse, one in the “gets it” part of the world and another in the “jury’s still out” zone.

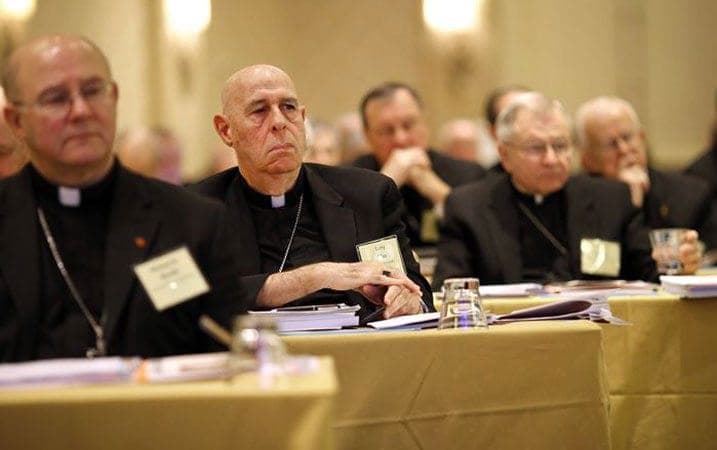

One should come from the fall meeting of the U.S. bishops in Baltimore opening Monday, and the other with the release of a long-awaited new set of anti-abuse guidelines from the powerful Episcopal Conference of Italy, known by its Italian acronym CEI.

In the U.S., the bishops are expected to vote to amend norms adopted at the 2002 meeting in Dallas to place bishops under the same protocols as other clergy when it comes to the “zero tolerance” standard, meaning automatic removal from ministry after a credible charge of abuse.

Though the bishops have already announced their intention to do that in some form, they’ll need to work out exactly how. Under canon law the only superior of a bishop is the pope, not the bishops’ conference, so they’ll have to decide if they want to appeal to Rome to amend their norms, voluntarily submit themselves to a lay review group, or some other mechanism.

The bishops are also expected to take up the thornier matter of how to get to the bottom of the scandals surrounding ex-Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, including who facilitated his rise up the ladder despite concerns over sexual misconduct stretching back at least to the 1990s.

That’s become infinitely more complicated since Pope Francis turned down a request from the bishops for an Apostolic Visitation, meaning a Vatican probe, arguing that if he did it for the U.S. he’d have to do it everywhere. It’s doubtful the bishops can get the answers they’re seeking without access to Vatican records, and short of a visitation or a formal canonical trial, it’s hard to see how that might happen.

Perhaps what American Catholics really need to see right now, however, is their bishops trying, in recognition of the gravity of the case. After that, if the obstacle lies in Rome, then it’s Francis and not the USCCB who will have some explaining to do.

Whatever criticisms the U.S. bishops deserve for failing to finish the job sixteen years after Dallas, there’s no doubt that from a global perspective they’re in the “get it” camp. At the recently concluded October Synod of Bishops on young people, it was prelates from the U.S., Australia, Ireland, Germany and elsewhere pushing for strong language on the abuse crisis and a clear commitment to zero tolerance, which ran into a buzz saw of ambivalence from Eastern Europe, parts of Africa and Asia, and even some Western European settings.

For every critic in the States who blames the bishops for not having done enough, there’s a Catholic leader from another part of the world who thinks they’re far too obsessed with the abuse scandals already.

Speaking of those ambivalent Western European locales, that brings us to Italy.

During the synod, several leading Italian prelates on the drafting committee for the final document – including Archbishop Bruno Forte, considered one of the country’s top theologians, and Cardinal Lorenzo Baldisseri, who runs the synod for the pope – were influential in the decision to water down the language on the abuse crisis, to the point that there was no direct apology to survivors and no reference to “zero tolerance.”

(The justification given for the latter deletion was that it would be inappropriate to commit to anything ahead of a Feb. 21-24 summit on child protection Francis has convened for presidents of bishops’ conferences from around the world. Many bishops from parts of the world familiar with the abuse crisis found that almost unfathomable, as if to suggest that the Church’s commitment to “zero tolerance” is somehow still up for grabs despite Francis’s repeated vows that it’s now the law of the land.)

Among experts on the abuse crisis, it’s almost taken for granted that one of the next places it’s going to erupt is Italy.

An example cited by Italian reformers is Archbishop Mario Delpini of Milan, who’s been accused of covering up abuse cases when he was the auxiliary bishop and vicar general of the archdiocese. The accusation is that Delpini was informed by another priest that a young man had told him that a third cleric, Father Mauro Galli, had abused him sexually during a night spent in his residence.

Delpini was deposed about the case in 2014 as part of the civil prosecution of Galli, and what immediately strikes anyone who’s actually lived through a real “crisis,” in the sense of media attention, legal pressure, public protest, and so on, is how tone-deaf his responses seemed.

Delpini acknowledged that after he received the information, he made the decision to transfer Galli to another parish. When asked by interrogators if he was aware that at his new assignment, Galli was responsible for youth ministry, Delpini flatly said, “Yes, sure I was aware.”

If that’s not a fire waiting to explode, it’s hard to know what would be.

In that context, the new guidelines will be an important test of whether the Italian bishops are ready to get serious. Their choices are especially important, because many bishops in other parts of the world look to them as a signal of what the pope actually wants.

In the U.S., Crux’s national correspondent Chris White will be in Baltimore with full coverage; in Italy, our faith and culture correspondent, Claire Giangravè, will be doing the same for the CEI guidelines. Check the Crux site all week for their reporting.