ROME – If you’re an English-speaker who wasn’t living under a rock for the last fifty years, you know the name Christopher Hitchens. He was Anglophone culture’s most famous critic of religion, a brilliant and brazen wit who once had the audacity to try to steal Mother Teresa’s halo, and who not only was convinced God is dead but determined to keep polishing his obituary.

Imagine the shock you might feel, therefore, to hear that Hitchens actually had a secret conversion late in life and died a Christian believer.

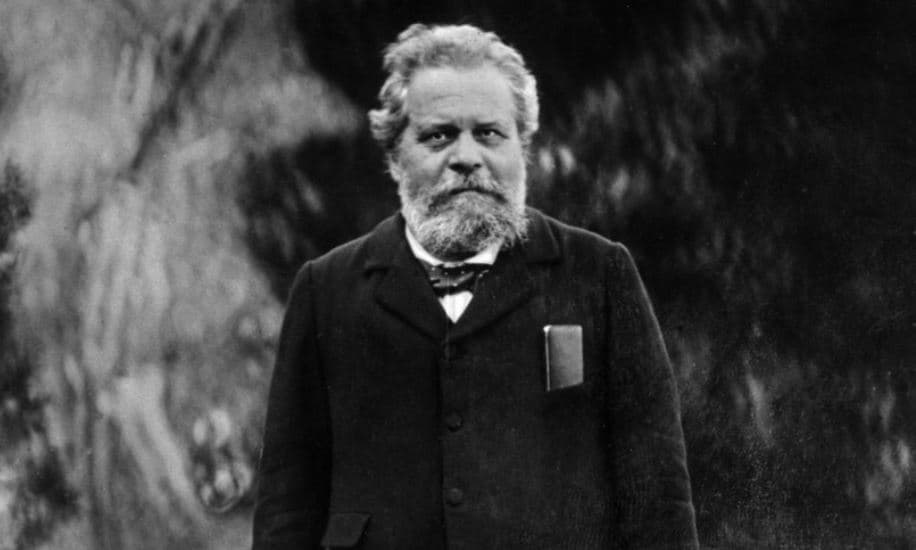

Italians are feeling something of that dismay this week, upon hearing reports that Giosué Carducci, the poet most identified with the risorgimento uprising in the late 19th century, and an ardent atheist and anti-cleric who once composed a celebrated “Hymn to Satan,” confessed his sins thirty years later and went to his death a faithful Catholic, albeit without ever announcing his change of heart.

The claim was made recently by Italian Cardinal Angelo Comastri, formerly the Archpriest of St. Peter’s Basilica and now living in retirement, in a series of daily video meditations during the month of May produced by the Italian Catholic TV network Telepace.

To this day, Italian children study the poetry of Carducci, the first Italian ever to win the Nobel Prize in literature. He’s remembered as an ardent nationalist and thus a bitter foe of the pope’s civil rule, who articulated the resentments many Italians felt over centuries of theocracy and clerical domination.

Here’s an indicative portion of his famed “Hymn to Satan,” unfortunately without the rhyme scheme that makes it work in the Italian original:

“As Martin Luther threw off his monkish robes/So throw off your shackles, O mind of man/

And crowned with flame, shoot lightning and thunder/Matter, arise; Satan has won.”

“Hail, O Satan O rebellion, O you avenging force of human reason!/Let holy incense and prayers rise to you!/ You have utterly vanquished the Jehovah of the Priests.”

Yet, according to the 77-year-old Comastri, Carducci by the end “arrived in the arms of Jesus, and it was Our Lady who brought him to us.”

As the story goes, in the 1890s, while he was in his 60s, Carducci was spending some time in Courmayeur, a charming mountain town located in Italy’s far northern Val d’Aosta region. While there, he began a dialogue with Abbot Pietro Chanoux, who ran a small hospice for visitors at the foot of one of the nearby Alpine mountains called the Piccolo San Bernardo, so called because tradition held it had been founded by St. Bernard in the 11th century.

Chanoux enjoyed a degree of fame as a preacher, but he was an ideal conversation partner for Carducci because he was also an amateur poet and a man of science. Chanoux established an observatory and botanical garden at the hospice, and it was his interest in classifying and studying the natural herbs of the Alps that led to the creation of the first serious scientific society devoted to the subject.

The claim is that one evening in 1895, while Carducci and Chanoux were talking, Carducci said he wanted his friend to hear his confession. From that point forward, Carducci allegedly returned to the faith, although in a largely clandestine fashion.

To appreciate how remarkable that idea must seem to Italians, recall that the same year, 1895, was the 25th anniversary of 1870, the year republican troops breached the Porta Pia in Rome and overthrew the Papal States, and for the occasion the new Italian government launched a national holiday on Sept. 20 to commemorate the defeat of the pope. When a series of local mayors decided not to host celebrations because Pope Leo XIII called on Catholics to boycott the new holiday, the national government declared those mayors suspended and illegitimate.

The idea that a hero of the republic would choose that moment to return to the faith, therefore, can’t help but seem terribly ironic.

We know of Carducci’s return thanks to the 1980 beatification cause of St. Luigi Orione, who founded a religious order of men to advance the new social teaching of the Catholic Church in the late 19th century. According to the paperwork for the cause, Orione learned of Carducci’s confession and conversion directly from first-hand sources during his travels across Italy.

According to Orione’s recollections, Carducci was asked why he didn’t want to reveal his decision, and his answer was, “I’m too weak to say it strongly.”

Assuming it’s all true, what’s the significance of Carducci’s secret conversion?

It probably doesn’t mean very much from a debating point of view. It’s hard to imagine that Hitchens, for instance, even if he knew that one of his intellectual forbearers had changed his spots, would have suddenly erupted into a “hallelujah!”

On a pastoral level, however, perhaps the moral of the Carducci story is that in religion, like politics, there are no permanent friends or enemies. The difference is that in politics, what’s permanent are interests.

In religion, on the other hand, what’s permanent is hope – even for those who seem most distant from faith right now, because, in all honesty, you just never know.

Follow John Allen on Twitter at @JohnLAllenJr.