ROME – If ever proof were needed of Pope Francis’s indefatigable commitment to outreach, the fact that today he’s traveling to Vanimo in Papua New Guinea, the most remote corner of a country which already represents the world’s peripheries, to meet with people utterly unaccustomed to having world leaders come calling, surely delivers it.

This is a pope, in other words, literally willing to go the extra mile for an outstretched hand.

From another part of the world, however, recent days also have offered the pontiff a reminder of a hard truth about such outreach, which is that sometimes when you extend your hand, the other party is more inclined to slap it away than to grasp it.

The point arises in Ukraine, after Pope Francis recently spoke out against a new law banning Moscow-aligned religious organizations, which is clearly targeted at what remains of the Russian Orthodox Church in the country. Notably, the pope risked the ire of his own flock, which had backed the new law, in order to voice solidarity with the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, which traditionally has been part of the Moscow Patriarchate.

Under the heading of no good deed goes unpunished, a leading hierarch of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church delivered an emphatic “thanks, but no thanks” in reply, warning that any movement towards closer ties with the Vatican would lead his flock by a short path into what he called — obviously not one to pull his punches — “a stinking spiritual swamp.”

In the end, Ukraine seems ever more like a “high risk, low reward” scenario for Francis: He risks alienation among the country’s Catholics, many of whom regard him as already too inclined to placate their invaders, as well as strained relations with a government under President Volodymyr Zelensky trying to proclaim the country’s “spiritual independence,” without much to show for it so far in terms of reciprocity on the Orthodox side.

The current dynamics began in late August, when Zelensky signed the new law providing any religious body in the country with links to Moscow 90 days to sever them, or risk being banned.

(As a footnote, it’s not clear precisely what the law actually portends, since the UOC argues that it declared full independence from Moscow in May 2022 and thus should be exempt from any ban. The declaration stopped short of autocephaly, but it’s unclear if that ecclesiastical distinction will matter in Ukrainian courts.)

In any event, Zelensky hailed the law as a defense of national sovereignty.

“This is a law that protects Ukrainian Orthodoxy from dependence on Moscow and guarantees the dignity of the shrines of our Ukrainian people,” Zelensky said at the signing ceremony, staged on the eve of Ukraine’s Aug. 23 Independence Day.

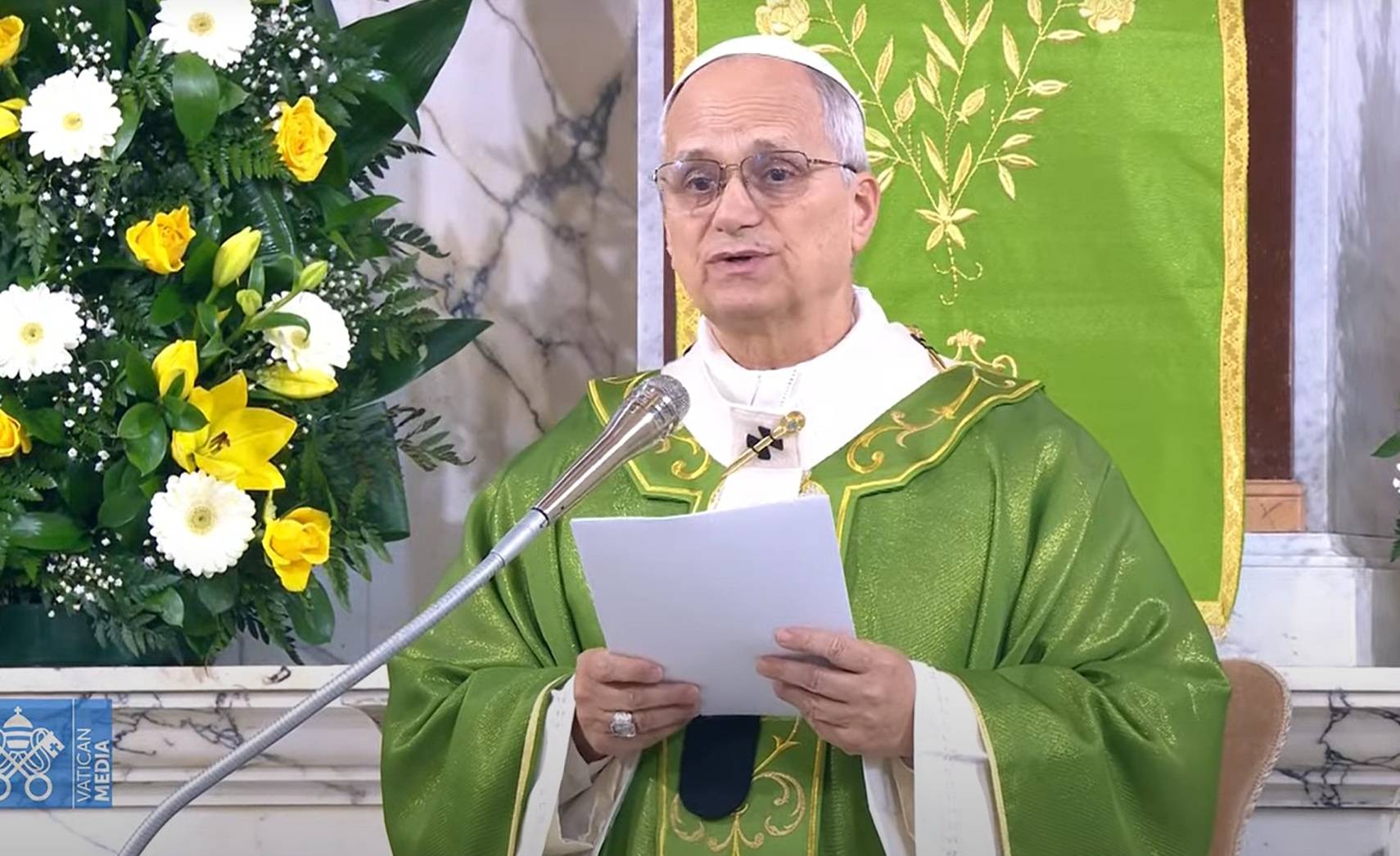

The measure has drawn international criticism as a restriction on religious freedom and an unjustified form of collective punishment for believers who simply want to maintain the spiritual traditions of their ancestors, without posing any threat to national security. Among the voices raising such concerns was Pope Francis, who spoke out in his Aug. 25 Sunday Angelus address.

“Let those who want to pray be allowed to pray in what they consider their church,” Francis said at the time. “Please, let no Christian church be abolished directly or indirectly. Churches are not to be touched!”

If he was expecting gratitude from the traditionally Moscow-aligned Orthodox in Ukraine, that’s not exactly what followed.

On the day the new law took effect, Metropolitan Luke Kovalenko of Zaporizhzhia, the city in southeastern Ukraine whose nuclear power plant is currently under Russian occupation, held a diocesan assembly to discuss their response. Widely considered an important, hardline force in Orthodox affairs, Kovalenko laid out four options: Joining another branch of Orthodoxy in Ukraine, affiliating with the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople instead of Moscow, privately transferring parishes and communities to other jurisdictions, and proclaiming full autocephaly.

In the end, Kovalenko rejected all four. He recommended instead that his church go underground if the new law is actually enforced, even recommending that priests begin hiding their vestments and sacred vessels to prepare for life in the catacombs.

Vis-à-vis the pope, most telling were Kovalenko’s reasons for rejecting any linkage with Constantinople. Here’s what he said, according to a summary provided by the press service of his diocese.

“Next year Patriarch Bartholomew is going to make a ‘breakthrough’ in the matter of ‘restoring unity’ with the Roman Catholic Church,” he said. “In particular, the Phanariots [a disparaging term for followers of Constantinople] are publicly talking about the possibility of a common celebration of Easter with the Catholic world in the very near future. After which the restoration of Eucharistic and prayerful communion should follow.”

“In light of this, our transition under Constantinople means only one thing: We will move further and further away from the Orthodox faith, following the Phanar’s course towards unity with the Vatican,” the metropolitan said.

“By the way, with the Vatican, which every year more and more openly supports LGBT issues and other ‘values’ alien to Christianity,” he added. “Do we want to plunge into a new union, a stinking spiritual swamp, together with the Patriarchate of Constantinople in the future?”

“I think this question can safely be considered rhetorical,” Kovalenko concluded.

To sum up, in the metropolitan’s logic, Constantinople equals Rome, and Rome, especially under Francis, means heresy … which is, needless to say, not exactly a prescription for détente.

Granted, not everyone in the Ukrainian Orthodox Church likely feels the same way. Nonetheless, Kovalenko’s open contempt is a reminder that there’s a hard core in the broader Russian Orthodox universe that simply will never accept any overtures from Rome, no matter how ardently a pope may propose them.

To put the point differently, this Ukrainian prelate has offered confirmation of an ineluctable truth about dialogue and reconciliation, one which an Argentine pope, of all people, should be in a position to grasp: To wit, it always takes two to tango.