A key idea of the new “Synodal Church” is “walking together” and “listening” to each other.

A new document from the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (DDF) looks at a major issue facing the Church on the continent of Africa, polygamy – and more precisely, polygynous marriage – and purports to be an exercise in just such synodal listening and walking together.

Whether the document passes the test is a legitimate question, and readers of the new document may wonder not only which way the DDF is going with its treatment of the matter but also how much listening went into its preparation.

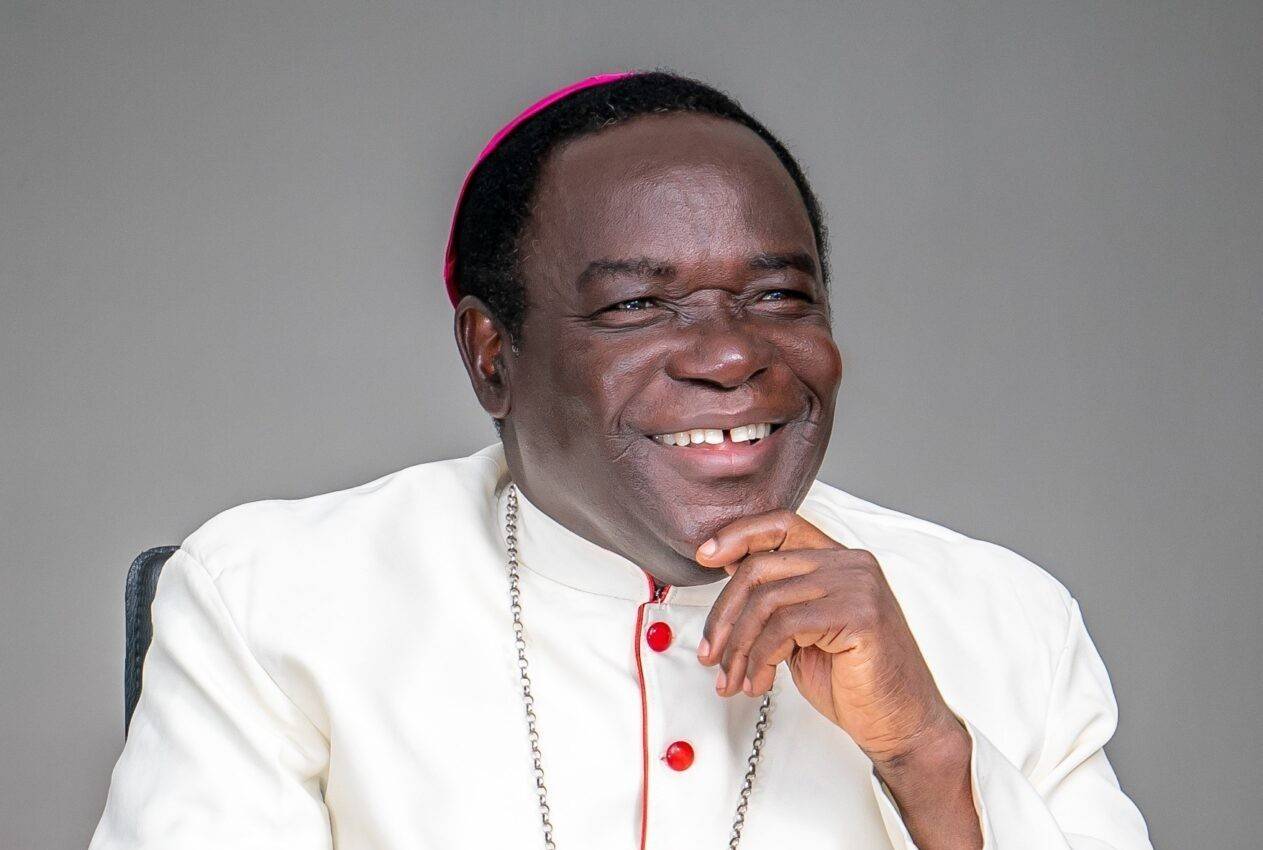

During the international conversations in and around the synod assemblies over the Francis pontificate, African bishops and other Catholics spoke a good deal about how polygynous marriage affects the Church on their continent.

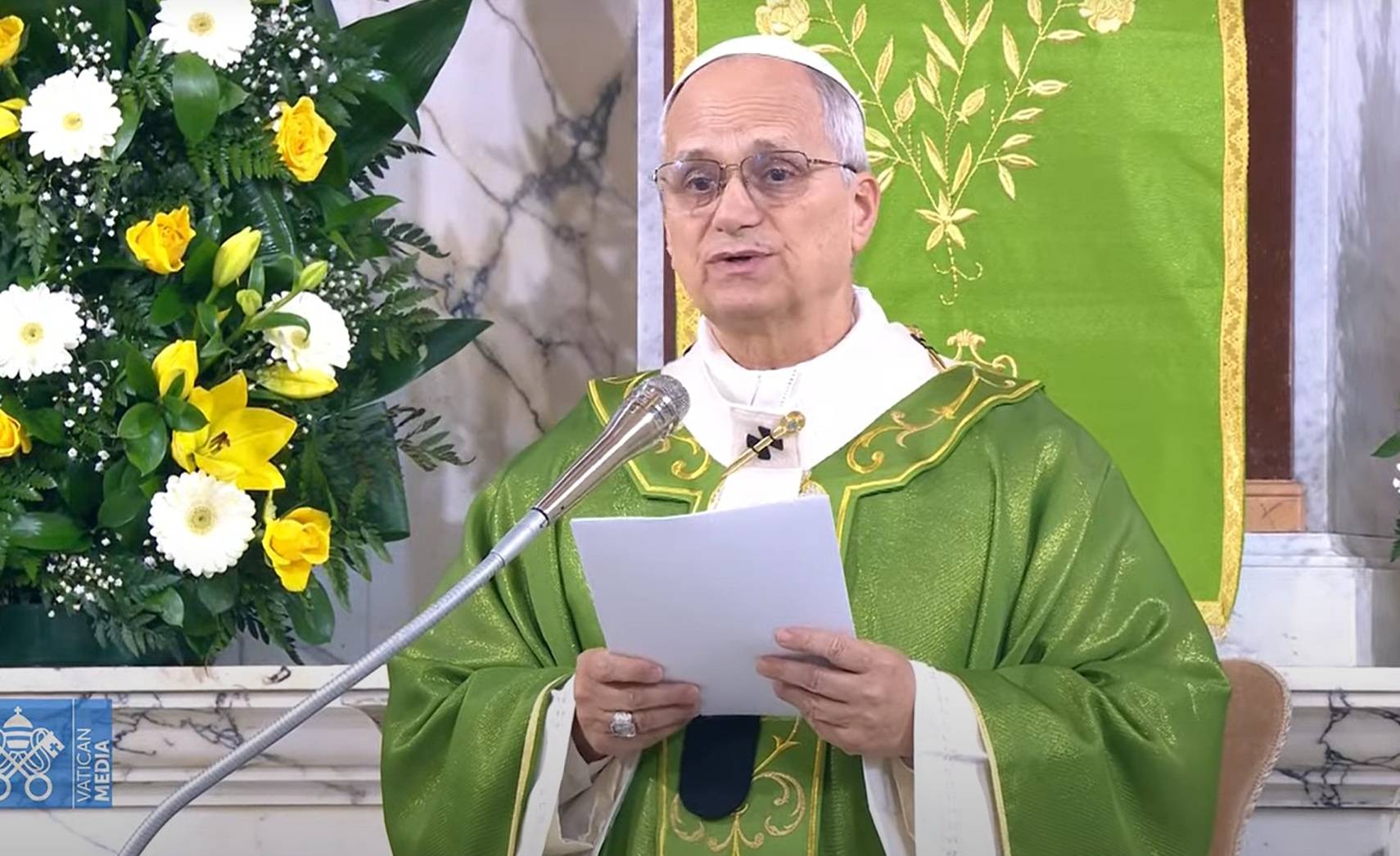

In response, the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith under Cardinal Victor Manuel Fernandez prepared and published this week a document, Una Caro: In Praise of Monogamy. Una caro is Latin for “one flesh” and recalls the teaching in Genesis (2:24) and the Gospel according to St. Matthew (19:5-6), according to which “a man shall leave father and mother, and shall cleave to his wife; and they shall be two in one flesh.”

In fact, leaders of the Church in Africa had been talking about the issue for a great many years before Pope Francis’s synodal process got into full swing. In 2016, the Symposium of Episcopal Conferences of Africa and Madagascar (SECAM) issued a document reflecting on “difficult” matrimonial situations like polygamy.

“A greater number of African families encounter series of challenges among which is the problem of polygamy. This challenge should invite the Church to accompany pastorally the polygamous men and to be witness of the divine mercy of God, while exhorting them to conversion,” they wrote, adding they “should avoid all that could lead to the recognition of such marital union so as to keep intact the Christian ideal of monogamy.”

Among the problems polygamy raises are stark realities, not least of which is the fact that ending polygamous relationships leaves some wives abandoned.

The problem does not affect only a few isolated countries or cultures on the vastly populous and diverse continent, nor are the bishops the only ones noting it.

Polygamy is still prevalent in many countries in the Horn of Africa and East Africa, Sudanese activist Hala al-Karib told Associated Press. Al-Karib runs the Strategic Initiative for Women in the Horn of Africa, a network of civil society groups. “Polygamy is contributing to massive chaos,” she said in 2018. “It really victimizes children and their mothers.”

In “Condemned and Condoned: Polygynous Marriage in Christian Africa” – a 2019 academic paper published in the leading The Journal of Marriage and Family – researcher Victor Agadjanian documents “a contrast between church leaders and rank-and-file members, the latter being generally more accepting of polygyny.”

“Both condemnation and toleration of polygyny by Christian churches reflect the complexities of the transformation of sub-Saharan marital systems and of the role that religion plays in that process,” Agadjanian writes.

“Historically, most Catholic and Protestant missions in Africa condemned polygyny as incompatible with Christian doctrine and values and even as a source of abuse against women, and the prevalence of polygyny today is indeed somewhat lower in areas where the presence of Christian missions has been the longest,” he continues.

“Yet, the reality has often conflicted with this seemingly unambiguous stance, especially as Christian churches became increasingly indigenized, ideologically and organizationally, in many parts of the sub-continent,” he said.

Agadjanian’s paper looks in particular at a predominantly Christian district in Mozambique, a former Portuguese colony located in in southeast Africa.

The country is 67 percent Christian and 18 percent Muslim. Although Mozambique is a former possession of a traditionally Catholic European country, Catholics are only 17 percent of the population.

“Condemned and Condoned” in fact looks closely at the varied Christian population, which is mostly of Evangelical, Baptist, and other Protestant bodies.

Interestingly, he found significantly lower levels of polygamy among Catholics and no significant difference across other Christian denominations and members of Islam, which allows men to have multiple wives.

Agadjanian found 13 percent of Catholics in Mozambique accepted polygamy, while 79 percent strongly opposed it; the others were undecided on the issue.

This is broadly in line with what bishops are facing in many African nations.

In 2024, SECAM issued its report on polygamy for the Synod of Bishops meeting on Synodality.

“Polygamy is a prevalent reality in many African countries, posing a significant pastoral challenge for the Church. This challenge arises both from individuals who were already in polygamous relationships before embracing the faith, as well as baptized members who enter into polygamy after their conversion,” the African bishops said.

The bishops’ “primary concern at the recent Synod was to emphasize the importance of pastoral care and accompaniment for those already in polygamous unions—whether Christians or non-baptized individuals seeking the faith,” the bishops said.

A year later, still during the Synod process, the African bishops highlighted that cultural and economic factors sometimes make it difficult for individuals in such unions to simply separate, especially affecting women and children.

The Church’s synodal approach, they stressed, is one of inclusion, not exclusion. “No one should be left behind,” they said.

“Monogamy is not simply the opposite of polygamy,” Fernandez writes in Una caro. “It is much more, and its deepening allows us to conceive marriage in all its wealth and fecundity,” he continues.

The bishops of Africa are not likely to object to that, which is fine as far as it goes.

In much of the document, which runs to 40 pages, Fernández focuses however on an issue of greater importance to contemporary Western societies than to Catholics or anyone else in Africa.

“The question is intimately linked to the unitive purpose of sexuality, which is not reduced to guaranteeing procreation, but helps the enrichment and strengthening of the single and exclusive union and the feeling of mutual belonging,” the cardinal writes.

And that is not the only way in which Una caro appears to look rather northward of the African continent.

Hans Urs von Balthasar, Karl Rahner, the von Hildebrands (all of them) are mentioned in the DDF document. One supposes there is nothing wrong with using European theologians from the mid-20th century to tackle the pastoral problem of African polygamy in the 21st, but still.

Turning to the French philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas, Fernández writes, “Sexual desire, when it moves within this dynamic of the face of the other, can adequately hold together sensitivity and transcendence, self-affirmation and recognition of otherness.”

This is a cardinal who got a good deal of coverage for his authorship of titles such as Heal Me with Your Mouth: The Art of Kissing and The Mystical Passion: Spirituality and Sensuality, both sadly out of print.

The Argentine prelate was perhaps, therefore, true to form in deciding to include passages from several love poems in his official Vatican document, though none were from African poets.

One struggles to find almost any attention given in Una caro to the family issues facing wives and children most hurt by polygamy. One rather finds the issue treated as a matter of sexual lifestyle viewed through a mid-20th century theological lens aided by a smattering of verse.

Church leaders of Africa used the Synodal Way championed by the Vatican to address one of the most pressing issues facing Catholics on the continent.

The Vatican’s doctrine office may have dropped the ball when it was taken at its word on what synodality was supposed to mean.

Follow Charles Collins on X: @CharlesinRome