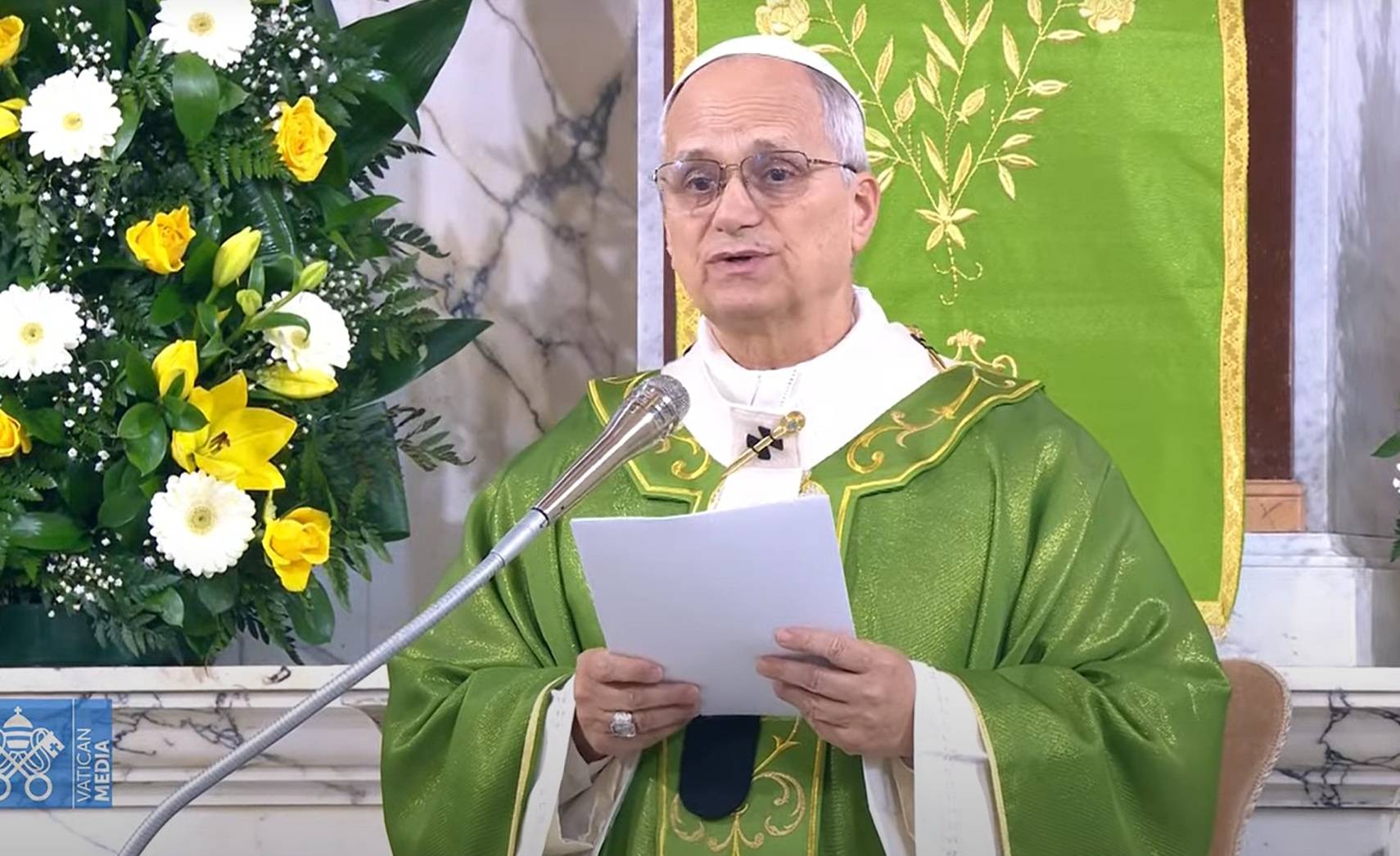

ROME – Today marks the release of the initial set of excerpts from Pope Leo XIV’s first-ever sit-down interview with a journalist, which comes in the form of the landmark new book León XIV: ciudadano del mundo, misionero del siglo XXI, meaning “Leo XIV: Citizen of the World, Missionary of the 21st Century,” released by Penguin Peru in Spanish and coming shortly in other language editions.

Let us get the obvious out of the way: This book is a work of genius, a profound guide to both the mind and the heart of the new pontiff, which only a gifted student of Catholic life and an experienced journalist could have delivered. I offer that judgment with complete objectivity, despite the fact that the author Leo chose to make his debut for is not only the Senior Correspondent of Crux but also my wife, Elise Ann Allen.

Okay, perhaps I’m slightly biased. Nonetheless, the fact remains that this book is how Pope Leo XIV has chosen to introduce himself to the world, and that makes it a moment of tremendous importance.

The small antipasti from the book we’re getting today almost certainly won’t be the most substantial items on the menu, but they’re still tasty.

They open with the reveal that if Peru and the U.S. were to play each other in the World Cup, the pope would cheer for Peru on account of what he calls his “affective bonds” with the country. He then veers into multiple other subjects, including the geopolitical function of the papacy, the press for peace in Ukraine and matters beyond, the role of the U.N., polarization and income gaps. Each point is treated only briefly, but in suggestive ways that no doubt will be unpacked in the full interview.

Today’s offerings end with Leo’s reflections on synodality, and an attentive reading of that section reveals a distinctively three-pronged manner in which Leo XIV is inclined to treat the legacy of his beloved, but also unavoidably controversial, predecessor Pope Francis.

First, Leo pledges unabashed loyalty to the substance of what Francis was about.

“Synodality is an attitude, an openness, a willingness to understand. Speaking of the Church now, this means each and every member of the church has a voice and a role to play through prayer [and] reflection,” he told Elise.

“It’s an attitude which I think can teach a lot to the world today,” Leo said of his predecessor’s cornerstone agenda item. “A little bit ago we were talking about polarization. I think [synodality] is sort of an antidote. I think this is a way of addressing some of the greatest challenges that we have in the world today.”

It would hard to issue a more full-throated endorsement. Leo even gently wagged a papal finger at hierarchs who may not want to get on board.

“Sometimes bishops or priests might feel, ‘synodality is going to take away my authority,’” he said. “That’s not what synodality is about, and maybe your idea of your authority is somewhat out of focus, mistaken.”

Yet at the same time, perhaps thinking in part of those Catholics who had a sort of allergy to virtually anything they perceived as originating with the Argentinian pope, Leo also gently suggests the idea in itself has much deeper roots.

“The process began long before the last synod, at least in Latin America,” he said. “I spoke about my experience there,” perhaps referring to a passage in the book in which he discusses how a participatory and dialogic spirit grew up in Latin America. He appears to suggest that what we today know as synodality was actually pioneered by the Second Vatican Council.

“I think [synodality] offers a great opportunity to the Church and offers an opportunity for the Church to engage with the rest of the world,” he said. “Since the time of the Second Vatican Council, I think that’s been significant, and there’s a lot to be done yet.”

In other words, he’s saying that no matter what you may have thought of Francis personally, much of what he stood for — however idiosyncratically it may have been expressed at times — actually drew on much deeper, widespread and essentially non-ideological currents in the church.

Finally, Leo offers a hint that preserving the ideal of synodality doesn’t necessarily mean all the structures, procedures and systems Francis himself put into place.

“There are many ways that that could happen, of dialogue and respect of one another,” he said – meaning not necessarily through artifacts of the last synodal experience, such as the infamous round tables to foster “conversation in the spirit” which some participants found liberating but others saw as vacuous and unfocused.

Leo suggested what’s important is to preserve the spirit of synodality, while being open to different ways of implementing it.

“To bring people together and to understand that relationship, that interaction, that creating opportunities of encounter, is an important dimension of how we live our life as church,” he said.

So, in miniature we have a Pope Leo three-step when it comes to his predecessor: Loyalty to the substance, attention to its deeper ecclesiastical roots to avoid undue personalization, and a willingness to be flexible about ways and means.

It’s the sort of balanced and careful approach one might expect from a pope who understands that he took over from a visionary, but also a lightning rod – and that for Francis’ imprint to endure, it may need to be pruned as well as pressed. That’s a keen insight into Leo’s mind – and that’s just day one in terms of the full harvest from Ciudadano del mundo, misionero del siglo XXI.