ROME – In the classic 1996 film “Jerry Maguire,” early on our hero, a highly successful agent representing athletes, has a crisis of conscience. In his epiphany, he realizes that his business has become too dominated by money and volume, losing the personal concern for clients that’s supposed to be the heart of the affair.

He stays up all night to produce a document – he pointedly calls it a “mission statement” – which he titles, “The Things We Think and Do Not Say.”

Naturally, as soon as the document is circulated the agent gets fired, and the rest of the film is about him struggling to live up to the ideals he espoused.

The title of that mission statement, however, has a far broader application than just sports management. In virtually every walk of life, in any industry or occupation or avocation, there are topics considered off-limits in terms of public conversation – not because they’re wrong or offensive, but because the politics of a given situation render them taboo.

Saying those things out loud – the things we think but do not say – therefore requires a measure of courage, or self-confidence, or calm in the face of possible blowback, and probably all three.

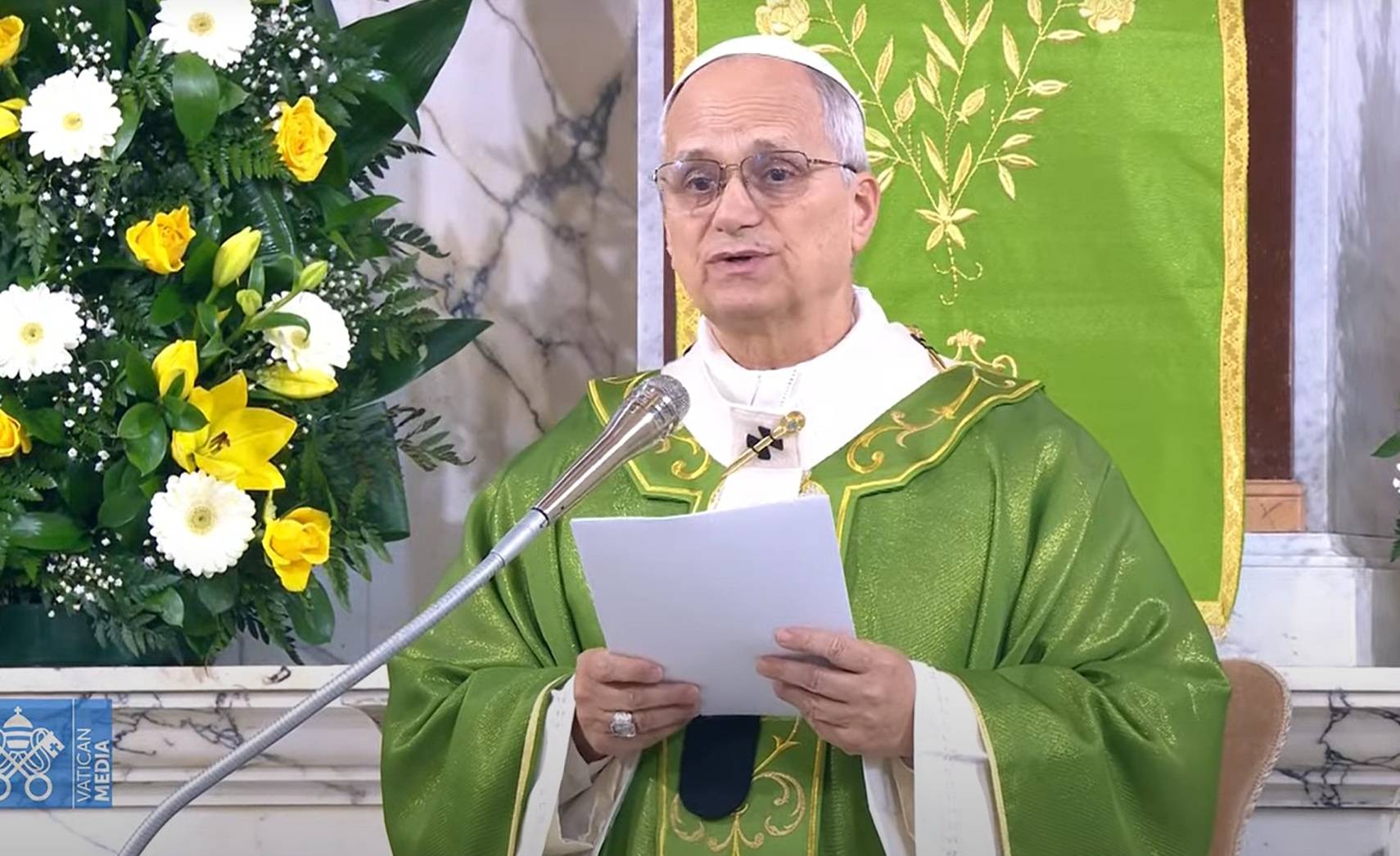

All of which brings us to the recent extended interview Pope Leo XIV gave to Elise Ann Allen of Crux, which is published in installments on the Crux site and which forms part of her new biography of the pontiff, León XIV: ciudadano del mundo, misionero del siglo XXI, or “Leo XIV: Citizen of the World, Missionary of the XXI Century,” published in Spanish by Penguin Peru and coming soon in other languages.

Among the host of fascinating elements are the pope’s comments on the sexual abuse crisis, which will strike anyone who listens to the usual public rhetoric on the subject as something of a departure.

By now, church leaders have learned a few hard truths about talking about the scandals. For instance, no wants to hear them make excuses or shift blame, and if they seem to be doing that, public opinion will come down on them like a ton of bricks. Likewise, if a church leader appears insensitive to the suffering of victims, backlash will be swift and severe.

As a result, church officials have developed a basic script for discussing the scandals in public: Begin with concern for victims, acknowledge the church’s failures, refer to an ongoing process of reform without claiming the problem has been solved, and avoid anything that could be taken as denying or minimizing the reality of the suffering that’s been caused.

While all of that is absolutely appropriate, it often means that there are a few things that many Catholics might feel about the crisis that just don’t get said out loud.

That is, these things don’t get said out loud until now.

In his interview with Elise, Leo XIV said all the right things on the abuse crisis, calling for “authentic and deep sensitivity and compassion” for victims, expressing frustration over delays in the investigation and prosecution of abuse cases, and insisting that victims must be “accompanied” by pastors and other church leaders.

What’s striking, however, is that’s not all he said. He added two other points, which, frankly, many Catholics probably have thought at one point or another, but which most of us have become too gun-shy to pronounce.

First, the pope said that in addition to protecting the rights of victims, the church also has to protect the due process rights of priests and other accused parties, because although the vast majority of reports of abuse turn out to be justified, there nevertheless have been cases of false allegations.

“People are beginning to speak out more and more: The accused also have rights, and many believe that those rights have not been respected,” he said. “There have been proven cases of some kind of false accusation. There have been priests whose lives have been destroyed.”

This truth, he said, has important consequences for the administration of justice.

“The fact that the victim comes forward and makes an accusation, and the accusation presumably is accurate, does not take away the presumption of innocence,” he said. “The priests also have to be protected, or the accused person has to be protected, their rights have to respected.”

Anyone who’s been paying attention to the arc of the abuse crisis has to know that two things are true: Every charge of abuse must be taken seriously, but false accusations are possible.

The emblematic case is the late Cardinal George Pell, who spent more than 400 days in an Australian prison over patently preposterous charges of sexual abuse before being exonerated by the country’s Supreme Court. At lower levels and in less spectacular fashion, other priests have faced the same Star Chamber justice, either from ecclesiastical tribunals or civil courts.

We all know this to be true, but it has become difficult to say because it can smack of protecting priests at the expense of victims.

Second, Leo XIV said that while recovery from the abuse crisis is critically important, the church can’t forget the rest of its mission.

“We can’t make the whole church focus exclusively on this issue, because that would not be an authentic response to what the world is looking for in terms of the need for the mission of the church,” the pope said.

That, too, is something many Catholics probably have thought at one point or another but learned not to speak aloud, for fear of seeming to minimize the importance of reform.

In the end, perhaps the pope’s candor is, in part, a reflection of the times. We’ve lived with the abuse scandals long enough now that perhaps a measure of maturity in public discourse has arrived, in which certain things can be said without automatically triggering accusations of denial or cover-up.

Yet it’s also likely that Leo’s comments also say something about the man. This appears to be a pope willing to describe reality as he sees it, however inconvenient or politically incorrect that may seem … convinced, perhaps, that in the end, the truth is its own best PR strategy.