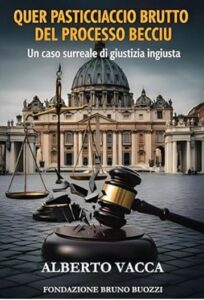

ROME – This past June, a book appeared by a veteran Italian intellectual named Alberto Vacca, the title of which seemed to perfectly capture the tawdry reality of the Vatican’s so-called “Trial of the Century.” It was: What an Ugly Mess in the Becciu Trial: A Surreal Case of Unjust Justice.

ROME – This past June, a book appeared by a veteran Italian intellectual named Alberto Vacca, the title of which seemed to perfectly capture the tawdry reality of the Vatican’s so-called “Trial of the Century.” It was: What an Ugly Mess in the Becciu Trial: A Surreal Case of Unjust Justice.

“Ugly mess” seems about right, given that we’re talking about a trial riddled with procedural irregularities, one which featured charges of the chief prosecutor colluding with two shady Italian laywomen to cook the testimony of the star witness, and where the presiding judge is now under investigation in Sicily for alleged mob ties.

This is the trial which was supposed to represent a landmark moment in the Vatican’s press under Pope Francis for greater transparency and accountability, and which ended up instead, at least in the popular mind, as a synonym for a legal farce.

To recap, the trial pivoted on a failed $400 million real estate deal in London, and featured charges of financial crime against ten defendants, including, for the very first time, a cardinal of the Catholic church, Italian Cardinal Angelo Becciu. In the end, the three-judge panel found nine of the ten guilty of at least some of the charges, and Becciu himself was sentenced to five and a half years in prison.

By the end, those verdicts struck a wide cross-section of opinion, including a healthy share of the College of Cardinals, as an exercise in star chamber justice, with the deck stacked against the defendants from the very beginning – in part, by direct papal edict. Things got so bad that some Italian commentators actually compared Becciu — who, honestly, was never a sympathetic figure when he was at the height of his Vatican powers — to Dreyfus as a victim unjustly railroaded for political reasons.

The appeals phase of the process, which opened this week, hasn’t exactly done a lot so far to rehabilitate the image of the original trial.

To begin with, the panel hearing the appeal, led by presiding judge Archbishop Alejandro Arellano Cedillo, a Spaniard and member of the Workers of the Kingdom of Christ community, accepted a defense motion to have the Vatican’s lead prosecutor, veteran Italian mob lawyer Alessandro Diddi, recused for alleged misconduct.

Specifically, the defense charged that a series of Whatsapp messages recently published in the Italian media confirm that Diddi conspired with Francesca Immacolata Chaouqui, infamous from the Vatileaks 2.0 scandal, and Genoveffa Ciferri, a consecrated secular Franciscan and self-described geopolitical consultant who once worked with the Italian security service. Together, so the accusation goes, the three shaped the testimony of Italian Monsignor Alberto Perlasca, a key prosecution witness, to do maximum damage to Becciu.

(The theory goes that Chaouqui blamed Becciu for blocking Benedict XVI from pardoning her during the Vatileaks 2.0 affair, and worked with Ciferri, a longtime personal friend of Perlasca, to wreak payback. Diddi, supposedly, went along in order to secure a conviction by any means necessary.)

By permitting the challenge to go forward, the appeals court at least signaled that it deserves to be taken seriously.

Diddi had three days to respond, and now the matter now rests with the Vatican’s Court of Cassation, or Supreme Court, which is composed of four cardinals. American Cardinal Kevin Farrell presides, and the other three are Cardinals Paolo Lojudice of Siena, Matteo Zuppi of Bologna, and Mauro Gambetti, currently the Archpriest of St. Peter’s Basilica, President of the Administration of St. Peter’s, and Vicar General of the Vatican City State.

There is no timetable on how long it may take the four cardinals to reach a decision, a process complicated by the fact that two of them aren’t even in Rome.

In addition, the appeals court also upheld another defense motion to toss out the prosecution’s appeal of the verdict from the first trial, on the grounds that Diddi had failed to provide an adequate rationale for the appeal within the time frame specified in the Vatican’s penal procedure.

In the Vatican’s legal system, as in Italy’s, both the prosecution and the defense can appeal a verdict. Had the prosecution’s appeal survived the challenge, theoretically the court could have made some penalties more severe; as it stands, the only options now are to acquit the defendants, reduce their sentences, or leave them as they are.

It’s an especially humiliating result for Diddi, who in December 2024 published a book on the Vatican’s penal procedure, yet now has been revealed to have either ignored or never understood one of its principal codicils.

The soap opera elements of this story are so overwhelming that the risk is that the real issues raised by the trial may never see the light of day.

Let us suppose for a moment that the prosecution in this case was led by Atticus Finch, that the witnesses were all angels, and that the evidence was untainted, unimpeachable and solid beyond any reasonable doubt. Suppose the defendants were guilty as sin, and that the trial left no room for doubt about the fairness of their convictions.

In other words, suppose the Vatican’s civil justice system, as presently constituted, worked to perfection. Would all that place the process beyond objection? The answer is no, and here’s why.

In modern democratic societies, the hallmark of a truly legitimate system of justice is its independence. It must not be subject to the control of any external force, including the political establishment of the state in which it operates. It’s a principle with which Catholic social teaching agrees; St. John Paul II in 2000, for instance, said the judiciary in a democratic state requires its own “autonomous and constitutionally protected function.”

There is no such separation of powers in the Vatican, where the pope is the supreme executive, legislative and judicial authority. In terms of the Vatican’s judiciary, including its civil branch, the pope hires and fires the judges, he sets the rules of procedure, and he’s free to intervene in any case at any time. Pope Francis, in fact, used that authority liberally in the Becciu case.

In such a system, modern expectations of due process can never be satisfied, no matter how virtuous the individual actors may be.

To put it differently, the problem with civil justice in the Vatican isn’t just a particular prosecutor or a given trial. It’s structural, and it pivots on a complete lack of separation of powers. Until that underlying defect is addressed, no civil trial the Vatican conducts will ever be taken seriously by responsible jurists anywhere else, no matter how properly it may be run.

There are potential solutions.

The pope could voluntarily renounce his authority over the Vatican’s civil judiciary, making it autonomous – including investing it with the power to overturn executive actions should they violate civil law. (For instance, should the pope award a contract to a construction company by bypassing a competitive bidding process, the tribunal would have the authority to tell him no.) This would involve no compromise of the pontiff’s spiritual authority, since even the most expansive notion of papal primacy has never included adjudicating financial crime.

Another possibility is that the pope could exercise an option provided for in the 1929 Lateran Pacts but never exercised, allowing Italy to prosecute civil crimes committed on Vatican soil in the Italian legal system but using Vatican law. That would get the Vatican out of the business of staging civil trials altogether – and if the Becciu case is any indication, perhaps that would be for the best.

In any event, the separation of powers in the civil sphere, not the spiritual, will have to be addressed sooner or later. One hopes the “ugly mess” of the present case won’t delay that day of reckoning.