For our coverage of Pope Francis’s fourth anniversary, we reached out to Crux staff and contributors to allow them to determine the most memorable moments of the last four years. Our plan was to assemble a Top 10 list based on tabulating their votes.

However, with so many voices in the mix, there were simply too many possible outcomes. In most cases, the single most memorable event of one contributor didn’t even make the cut for the rest.

So instead of doing a Top 10 list, we decided instead to go a different route: Collecting what each of our staff and contributors saw as the key moment or element of the papacy, and presenting these vignettes in no particular order.

We would love to hear your voices too, so be sure to reach out to us on Facebook or Twitter.

Herewith, then, the official Crux review of memorable moments from the first four years of a remarkable papacy.

Holding Dominic Gondreau and hugging Vinicio Riva, Nirmala Carvalho

In April 2013 after the Easter Sunday celebrations in St. Peter’s Square, Pope Francis held Dominic Gondreau, an eight-year-old boy with cerebral palsy who was born three-and-a half months premature, weighing little over one pound.

“It was really, really powerful,” his mother Christiana later told reporters. “Almost like a crescendo of love. ‘This is going to happen and we’re going to make it happen.’ It was beautiful.”

When we saw it, we were all moved to tears. I remember his father later recounted that a woman whom he’d never met told him: “You know, your son is here to show people how to love.”

I believe this was a very powerful testimony, just as when, some months later, in November, apparently not caring if he was contagious, Pope Francis kissed Vinicio Riva’s painful sores, a symptom of a genetic disease called neurofibramatosis, in St. Peter’s Square.

“He didn’t even think about whether or not to hug me,” he later told reporters. “He caressed me all over my face, and as he did I felt only love.”

When full of love and tenderness, Pope Francis hugged the man, for me, this was special, as I know someone with the same illness and even though not so severe, I cringe even to shake hands with her.

I’m a sinner, Charles Camosy

In his first interview, asked to define who he is, Pope Francis replied that “I am a sinner.” That claim is important on several levels.

First, there’s his basic understanding of anthropology. We are flawed beings who need to keep this also at the front of our mind–particularly when it comes to the need for God’s mercy and the hesitation which we (should) have when coming to firm conclusions based on our own reasoning and intuitions.

We should be humbled by our sinfulness and that humility should leave us very hesitant to make firm convictions on the basis of our “experience.” Whenever possible we should, as Francis (mostly) does, stay close to the Gospel and tradition and teaching of the Church as the grace-filled guiding light.

But on another level, it has also changed the nature of the papacy. When a Pope leads with this, the aura of perfectly white-washed sinlessness and certainly infallibility falls away.

Along with Benedict’s resignation, Francis’s papacy, I think, has forever changed the view of the papacy as somehow granting the office holder some supernatural powers or even some inherent special character.

This pope is kind of like us … a sinner who’s trying to follow the very difficult demands of the Gospel. Sometimes he fails. Perhaps often. So do we. And that’s OK and it’s something, again, for us to keep right at the front of our minds.

Press conference on the plane back to Rome from Brazil, July 2013, Austen Ivereigh

John Allen, who was on the papal plane returning from World Youth Day in Rio de Janeiro, described Francis’s first airborne press conference as the kind of thing journalists dream about but never expect to experience — an hour-long, free-flowing question-and-answer session with the pope.

This has now become so normal that it no longer surprises us, but it’s easy to forget just how astonishing this was.

The Rio papal flight press conference, famous for triggering the “Who am I to judge?” headline, marked a new era in papal and Vatican communication, in which the pope acted as his own spokesman and reserved the right to speak to whomever, and whenever, he wished.

The press conferences have generated an extraordinary level of coverage and helped put the papacy back at the heart of world public affairs. But they have also generated unease and sometimes scandal, with Catholics who prefer popes to speak in carefully crafted statements reacting with dismay at Francis’s off-the-cuff comments.

The then-Vatican spokesman, Father Federico Lombardi, urged journalists early on to apply a different “hermeneutic” to Francis in spontaneous flow: it’s papal teaching, yes, but not the kind you get in documents.

Speech to U.S. congress, Chris White

Hearing the Holy Father speak aloud the words “the land of the free and the home of the brave” from the dais of the U.S. Congress in September 2015 was an unexpectedly emotional occasion for me.

Despite such bitter polarization in recent years, here was the leader of the Catholic Church bringing political leaders from both sides of the aisle together in a rare moment of genuine joy and enthusiasm that no State of the Union could come close to matching!

In that address, Francis used the occasion to recast the American Dream through the lens of Catholic social teaching. It proved to be an occasion to reconsider what’s best about America—and I hope it served as an examination of conscience for the entire nation.

Rather than using his time to lecture us about the moral failures of a country that has drifted far from upholding many of our Catholic ideals and values, Francis offered us something to aspire to. We would do well to revisit this address often and see how we’re measuring up to his challenge.

Also marking this address as one of Francis’s top moments in the past four years, Crux’s National Correspondent, Mark Zimmermann, highlighted the fact that lawmakers of opposing parties put partisanship aside to listen in rapt attention as the pope encouraged them to work together for the common good.

He also praised the remarks themselves, where Francis cited the example of four great Americans – President Abraham Lincoln’s work for liberty; Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s pursuit of justice and equal rights; Dorothy Day’s service of the oppressed; and Thomas Merton’s efforts to sow peace through dialogue and prayer.

Read the pope’s full remarks here.

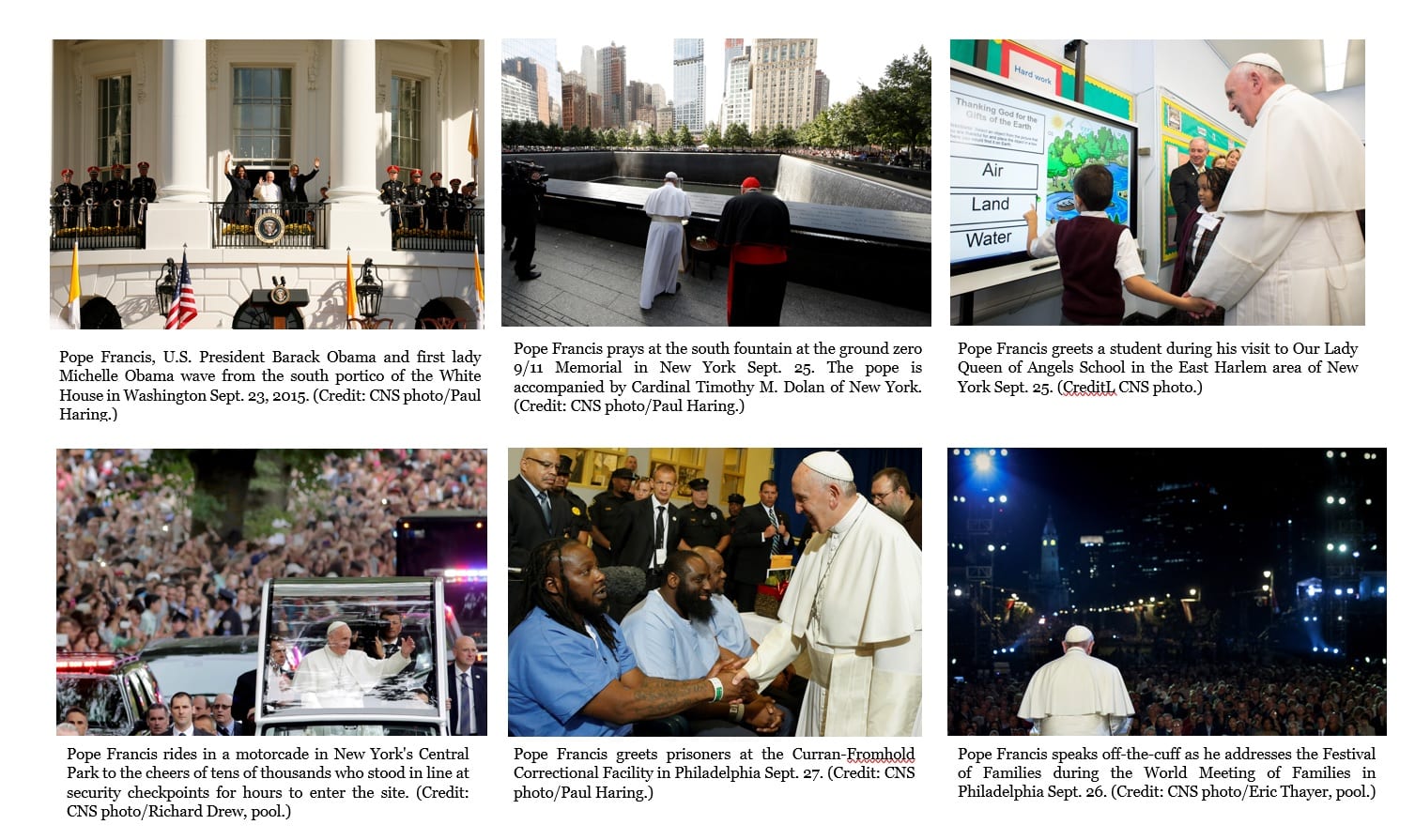

Pope Francis’s address to the U.S. Congress came during the Washington leg of his trip to Cuba and the United States. There were many memorable moments during his first-ever visit to U.S. soil: from his procession through Central Park, which gathered a crowd of more than 80,000 people to his attempts to use a smartboard during his visit to Our Lady Queen of Angels School in East Harlem.

The Synods on the Family, Charles Collins

When Pope Francis announced he would be holding two meetings of the Synod of Bishops in 2014-2015 to discuss the family, few people realized how controversial the process would become. After all, synods had usually been boring talking shops, with bishops for weeks giving monotonous speeches, before an anodyne statement was issued at the end.

It soon became clear that the 2014 Extraordinary Synod on the Family would be different: A speech by Cardinal Walter Kasper at the February 2014 Consistory advocating communion for the divorce-and-remarried was the opening salvo in a battle over the reception of communion by couples in “irregular unions” which at times overshadowed other serious issues surrounding familial life, both in and out of the synod hall.

Several cardinals answered Kasper in books and articles published in the lead-up to the synod (both in favor of and against the proposal), and there were reports of heated words during the synod sessions.

The debate continued at the Ordinary Synod which met the next year, and only intensified when Pope Francis issued the Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation Amoris laetitia in 2016.

The entire process showed the possible contradictions in the pope’s desire for a more synodal church, and his lack of hesitation in using the full power traditionally vested in his office.

Mercy, Father Raymond de Souza

The Jubilee Year of Mercy, which began on Dec. 8, 2015 and closed on Nov. 20, Feast of Christ the King, was the capstone of a pontificate that has ensured that mercy touches all aspects of the Church’s life and does not remain limited to the Divine Mercy devotion.

Despite the contradictions and confusions that have occasioned much commentary these past years, it is the compassion of the Holy Father that makes the deepest impression upon me. An interview he gave recently to a Caritas magazine for the homeless in Milan where he advised Catholics to always give money to those begging in the streets, without worrying about what it might be spent on, was a good example.

For the pope to give an interview to a magazine for the homeless illustrates his solicitude for the poor and marginal. His advice to give the benefit of the doubt to all; to see the point of view of the afflicted one; to value the encounter rather than a particular result – all this is distinctively Francis.

Also distinctively his are his attempts to revitalize the Church’s corporal works of mercy, symbolized by the transformation of the Almoner’s office from a ceremonial position to an inspiring witness of practical charity.

Evangelii Gaudium, Laudato Si’ and Amoris Laetitia, blockbuster documents, John L. Allen Jr.

One way of explaining what popes do is, they issue documents. Popes produce mountains of verbiage, from encyclical letters to apostolic exhortations and plenty of other genres in between. Over the years it’s sometimes been an open question whether anyone is paying attention, and many of these documents vanish into obscurity before the ink is even dry.

Not so under Pope Francis, however, who’s produced three blockbuster texts that have raised eyebrows, stirring both imaginations and controversy.

Evangelii Gaudium in 2013 cemented Francis’s reputation as a progressive reformer in the spirit of the Second Vatican Council, while Laudato Si’ in 2015 made him the global chaplain of the push to limit climate change. Needless to say, Amoris Laetitia triggered fierce debate among the Church’s chattering classes for the pope’s cautious opening on Communion for divorced and civilly remarried Catholics, and the fault lines it’s opened up will help define Francis’s legacy.

One can agree or disagree with particular elements of these documents (for instance, was the dig at air conditioning in Laudato Si’ truly necessary?) What’s not open for discussion, however, is that when this pope puts pen to paper, the results are usually electric.

His ability to address Millennials, a misunderstood generation, Claire Giangravè

According to a 2016 Religious Landscape Study by the Pew Research Center, Millennials pray less, attend mass less and overall believe less than previous generations. But the “snowflakes” display a belief in life after death and in heaven, hell and miracles similar to that of older people, Pew surveys show.

Millennials, born between the early 80s and 2000s and left with nothing to believe in by their disenchanted parents, are the “snowflakes.” Allegedly they were raised to believe they are unique, they are hypersensitive and search for solace in their luminous and interconnected screens.

Admitting that only time can tell who these Millennials actually are, if anything, few have been able to address this misunderstood generation as capably as Pope Francis, the reason why he’s the only pope to ever grace the cover of Rolling Stone, something he’s done twice: once in the United States [reprinted also in Mexico and other Spanish speaking countries] and more recently, in Italy.

Francis’s unique communicative method speaks to Millennials in a very special way through his “realness,” his anti-establishment persona, his focus on mercy as an all-inclusive practice, and his savvy use of technology.

His prioritizing of the peripheries, a determining factor of his passport stamps collection, Inés San Martín

A papal trip is never gratuitous. Meaning, no pope ever chooses to do a pastoral visit to a country just because he “feels like it.” Yet in the past four years, and after promising that he had no intention to travel as much as his predecessors, he’s visited the four corners of the earth.

What’s more, he’s spoken about his “intention” to visit several other countries, way before the trips are confirmed. One reason for this is the fact that he knows he has the ability to raise awareness of the tragedies being lived.

The perfect example of this is South Sudan, the world’s youngest, but often forgotten, country. The ongoing civil conflict has taken thousands of lives, and millions are at risk of dying of starvation before the year is up. It’s still unclear if he’ll be able to visit the country, though armed conflicts didn’t stop him from going to the Central African Republic nor confirming a trip to Colombia. Yet the fact that he floats the possibility every so often, at least raises the profile of the country and the attention of the international community.

Similarly, his first trip outside of Rome was to the Italian island of Lampedusa, to honor the thousands of migrants who’ve died trying to reach Europe. Here he spoke about the “throwaway culture” and “globalization of indifference” for the first time. Three years later, seeing the crisis worsen not improve, he took a similar trip to the Greek island of Lesbos, this time calling the Mediterranean Sea a cemetery, and upping the ante by bringing 12 Syrian refugees back with him to Rome.

The choice of Lampedusa for his first foray was highly symbolic for Francis, son of immigrants himself, who said news reports of the deaths of desperate people trying to reach a better life had been like “a thorn in the heart.”

His trip to Mexico, where instead of staying in Mexico City he traveled across country to meet impoverished indigenous populations in Chiapas, victims of drug cartels in Morelia, and immigrants and refugees near the U.S. border in Ciudad Juárez. Francis’s Mexico trip shaped up as a “greatest hits” collection of his social teaching, delivered in the flesh and in his native tongue.