ROME – Weighing into the discussion of the possible discovery of life on Venus, the Vatican’s top man on all things outer space has cautioned against getting too speculative, but said that if anything living exists on the planet, it doesn’t change the calculus in terms of God’s relationship with humanity.

“Life on another planet is no different than the existence of other life forms here on Earth,” Jesuit Brother Guy Consolmagno told Crux, noting that both Venus and Earth, “and every star we can see in our telescopes, are all part of the same universe made by the same God.”

“For that matter, the existence of [other] human beings does not mean that God does not love me,” he said, adding that “God loves all of us, individually, uniquely, completely; He can do that because He’s God… that’s what it means to be infinite.”

“It’s a good thing, perhaps, for something like this to remind us humans to stop making God smaller than He really is,” he said.

Director of the Vatican Observatory, Consolmagno spoke after a group of astronomers released a set of papers Monday stating that through powerful telescopic images, they were able to detect the chemical phosphine in Venus’s atmosphere, and determined through various analyses that a living organism was the only explanation for the source of the chemical.

Some researchers dispute the argument, as there are no samples or specimens of Venusian microbes, arguing instead that the phosphine could be the result of an unexplained atmospheric or geologic process.

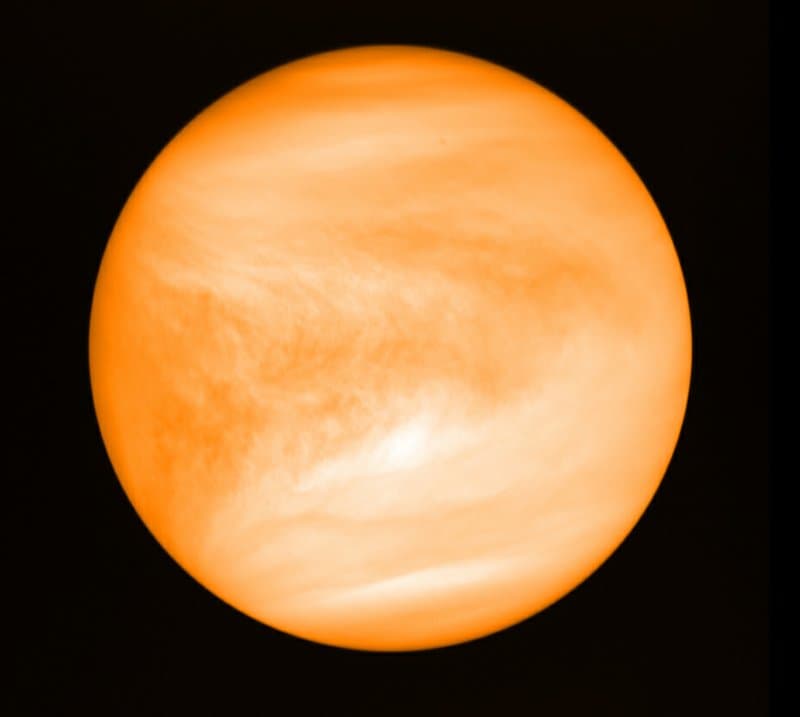

Named after the Roman goddess of beauty, Venus in the past has not been looked at as a habitat for something living given its sweltering temperatures and the atmosphere’s thick layer of sulfuric acid.

More attention has been paid to other planets, such as Mars. NASA has been forging plans for a possible mission to Mars in 2030 to study the past habitability of the planet by gathering rocks and soil to be brought back for analysis.

Phosphine, Consolmagno said, is a gas containing one atom of phosphorus and three hydrogen atoms, and its distinctive spectrum, he added, “makes it relatively easy to detect in modern microwave telescopes”

What is intriguing about finding it on Venus is that “while it can be stable in an atmosphere like Jupiter’s, which is rich in hydrogen, on Earth or Venus – with its acidic clouds – it should not survive very long.”

Though he doesn’t know the specific details, Consolmagno said the only natural source of phosphine found on Earth comes from certain microbes.

“The fact that it can be seen in the Venus clouds tells us that it is not some gas that has been around since the formation of the planet, but rather something that must be being produced…somehow…as fast as the acid clouds can destroy it. Hence, possible microbes. Maybe.”

Given the high temperatures on Venus, rising to around 880 degrees Fahrenheit, nothing can live on its surface, Consolmagno said, noting that any microbes where the phosphine was found would be in the clouds, where temperatures tend to be far cooler.

“Just as the stratosphere of the Earth’s atmosphere is very cold, so is the upper region of the Venus atmosphere,” he said, but noted that for Venus, “very cold” is equivalent to the temperatures found on the surface of Earth – a fact that was the basis of scientific theories as far as 50 years ago suggesting that there could be microbes in the clouds of Venus.

However, despite broiling excitement over the possible confirmation of the existence of these microbes, Consolmagno cautioned against getting carried away too quickly, saying, “the scientists who made the discovery are themselves very, very cautious about not over-interpreting their result.”

“It’s intriguing, and deserves further study before we start believing any speculations about it,” he said.

Follow Elise Ann Allen on Twitter: @eliseannallen