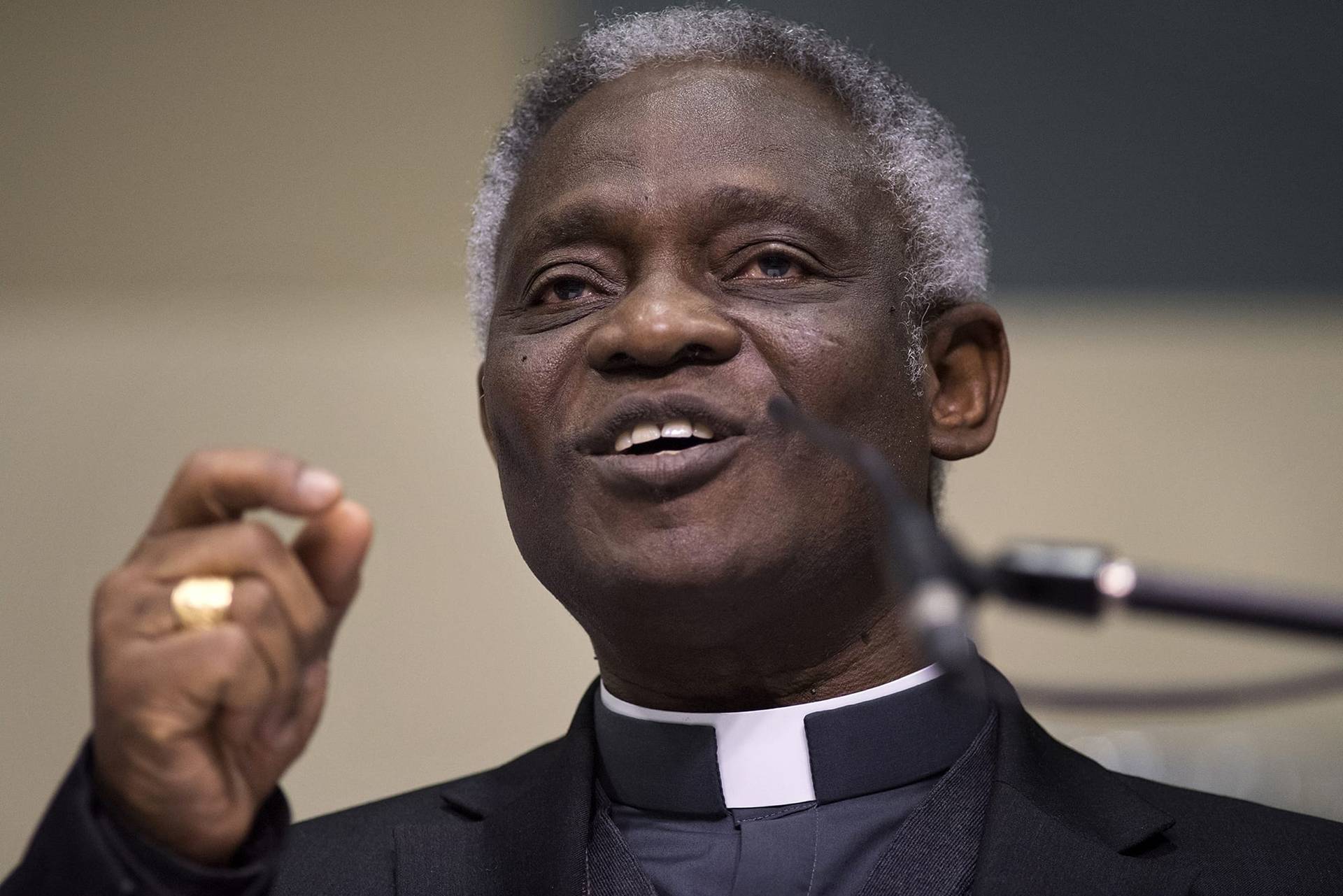

ROME — Probably no one person can reasonably be said to embody the soul of the Church on an entire continent, but Bishop Tharcisse Tshibangu of the Democratic Republic of Congo comes awfully close to being at least the living memory of African Catholicism.

ROME — Probably no one person can reasonably be said to embody the soul of the Church on an entire continent, but Bishop Tharcisse Tshibangu of the Democratic Republic of Congo comes awfully close to being at least the living memory of African Catholicism.

Now 80, Tshibangu was born in Kipushi in what was then still the Belgian Congo – not yet Zaire under strongman Mobuto Sese Seko, and certainly not today’s Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Ordained in 1959, the young Tshibangu was a precocious up-and-coming student riding the first wave of momentum towards a distinctively African way of engaging Catholic theology. In 1960, he dared challenge the views of the dean of his theology faculty at the Louvanium in Kinshasa, Belgian Monsignor Alfred Vanneste.

In a famous exchange on January 29, 1960, Tshibangu argued that Africans needed to consider finding their own approaches to theological questions, and not simply mimic the Western patterns of the missionaries who brought the faith to the continent.

Vanneste replied that he found no need for the idea of an “African Christianity,” since, after all, adaptation in the faith means rising to a higher level, not descending to a lower one. Today it may seem absurd that a Belgian ex-pat was lecturing an African on the right way to conceive of the faith in Africa, but back then native students just didn’t joust with their foreign teachers.

Tshibangu, however, stood his ground.

Explaining his self-confidence, he said it was “due to the fact we already had an in-depth knowledge of Africa, we knew who we were to become.”

He said the slogan among young African Catholic thinkers at the time was, “Christ has brought us universal salvation, but we have to remain authentically African.”

In a rousing address Wednesday morning to a conference on African Christian theology taking place at the University of Notre Dame’s “Globe Gateway” center in Rome, Tshibangu said he felt triumphantly vindicated nine years later when Pope Paul VI visited Kampala in Uganda and told his African audience, “You may, and you must, have an African Christianity.”

By that time, Tshibangu was no longer an eager young student, but an accomplished theologian in his own right. He had been named by St. Pope John XXIII to serve as a theological expert, or peritus, at the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), becoming the lone African to serve in that capacity.

Obviously Paul VI liked what he saw in Tshibangu, because one year later, at the age of 37, he was named an auxiliary bishop of Kinshasa. He held the post until 1991, when he was named the Bishop of Mbujimayi in Congo. He retired from that position in 2009.

Along the way, Tshibangu served as a university rector, founded theological journals, wrote books, and generally devoted his life to the cause of building up an authentically African way of living the Christian Gospel, including the Church’s intellectual reflection on the faith.

Rome, Tshibangu conceded, has sometimes been a bit leery of the push for a distinctively African faith. At one point in the John Paul II years, he said, the bishops of Congo proposed, and other prelates around the continent endorsed, the idea of holding an “African Council,” in keeping with the practice of holding regional councils in the early church.

Rome’s response, he said, typically boiled down to “we’ll see” followed by delay, and it never actually happened – although, he pointed out, two Synod of Bishops for Africa were called under John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI.

At the Africa conference on Wednesday, Tshibangu delivered a strong charge to the roughly 200 theologians, bishops, clergy and religious, and scholars in attendance.

“It is our duty to remain within African spiritual values, but also to open ourselves to everything humanity has produced and gives and presents for our consideration,” he said. “We must grasp the needs of Africa, the African soul, but also be a stakeholder in universal thought.

“It’s not just a question of African theology for Africans,” Tshibangu said, “but a theology that’s valid for one and all.”

Accomplishing that, he suggested, will require striking the right balance between the local and the universal.

“We have to know the characteristics proper to each church, what it has special unto itself [and] what it can contribute to the universal church, to the evolution of the world, and hence to the salvation of the world, which is the first aim and scope of theology,” he said.

“Let that be our basis, our ground, and our foundation,” Tshibangu said.

Whether that will actually be the basis of African Catholic theology going forward is, of course, anyone’s guess. It’s a pretty safe conclusion, however, that it’s already served as the foundation of Tshibangu’s long and remarkable career.