ROME — When Cardinal John Ribat of Papua New Guinea was young, he and his neighbors noticed that their well water tasted of salt. Crops also failed as the soil became salty.

Papua New Guinea consists of a large island in the Pacific Ocean surrounded by smaller islands and atolls. Residents of the island where his family lived moved inland to higher ground. They did not realize that they were early climate refugees, displaced as rising sea levels turned their fresh water brackish.

Other people have been less fortunate. Many who lived on lower-lying islands have been forced to take refuge on the large island. The Diocese of Bougainville resettled some on a plantation it owned.

“But local people are asking how long they will be there,” said Ribat. He wonders where thousands more will go as they are displaced and what conflicts might arise as a result of resettlement.

For Pacific islanders like those in his country, “the real issue is climate change,” said the cardinal, who is participating in the Synod of Bishops for the Amazon here from Oct. 6 to 27.

Villagers in his country risk displacement for other reasons, as well. Companies persuade them to sign away the land on which they traditionally have lived, and to which they have customary rights that are not recorded on paper.

Those companies then destroy the forest by cutting down trees for timber, opening mines or installing oil palm plantations, robbing people who traditionally use forest products for their livelihood, Ribat said.

The companies give villagers “false hope” by offering them money, but even if the payments are made, they do not compensate for the loss of the forest or for the destruction of the land that is a fundamental part of people’s identity, he said.

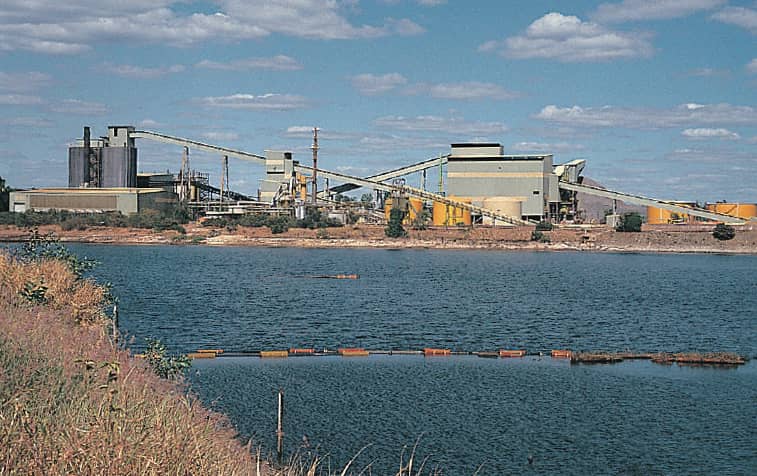

Mining has also been controversial in Papua New Guinea. Church leaders have spoken out against efforts to start seabed mining off the coast, Ribat said.

And on Oct. 18, the government shut down a Chinese-owned nickel mine in the wake of an Aug. 24 accident that dumped more than 50,000 gallons of toxic slurry into a bay in the coastal Madang province. The spill turned the water red and poisoned an important fishing area, he said.

For people who live along the coast, “the sea is home,” the cardinal said. The toxic spill has made that home — and the food it provides — unsafe.

Although Papua New Guinea is a fraction of the size of the Amazon, it poses special challenges for pastoral work.

Roads are few and poor, so church workers travel to remote communities on foot or by small plane and to islands by boat. Many villages see a priest only once every month or two. At one mission station where he worked, he and other priests would spend a month at a time walking from village to village.

Catholic missionaries now minister to several groups deep in the forest who traditionally have been semi-nomadic, and which only recently have come into contact with wider society. The Church would like to offer them the benefits of services like health care and education, but still “allow them to live their life as they are,” the cardinal said.

One important message from the synod, he said, is that the Church plays a crucial role in promoting respect for the culture and the dignity of original peoples.

Unlike the Amazon, where indigenous people are a minority, most of Papua New Guinea’s population is indigenous. And unlike both Latin America and Africa, where church workers who defend local communities’ rights often come into conflict with government officials, political leaders in Papua New Guinea tend to listen to the bishops on issues affecting people’s lives, Ribat said.

The regions are similar, however, in that there are not enough priests to administer sacraments in such widely scattered communities. While the island nation once received missionaries from Europe, Ireland and Australia, it now has more from Asian countries like the Philippines and India.

The synod has convinced the cardinal of the need for the Church to work across borders on common issues, especially in promoting an integral ecology. Upon returning home, he said, he plans to talk with bishops throughout the Pacific region about launching a network similar to those that have formed in the Amazon, Mesoamerica and Africa.

Crux is dedicated to smart, wired and independent reporting on the Vatican and worldwide Catholic Church. That kind of reporting doesn’t come cheap, and we need your support. You can help Crux by giving a small amount monthly, or with a onetime gift. Please remember, Crux is a for-profit organization, so contributions are not tax-deductible.