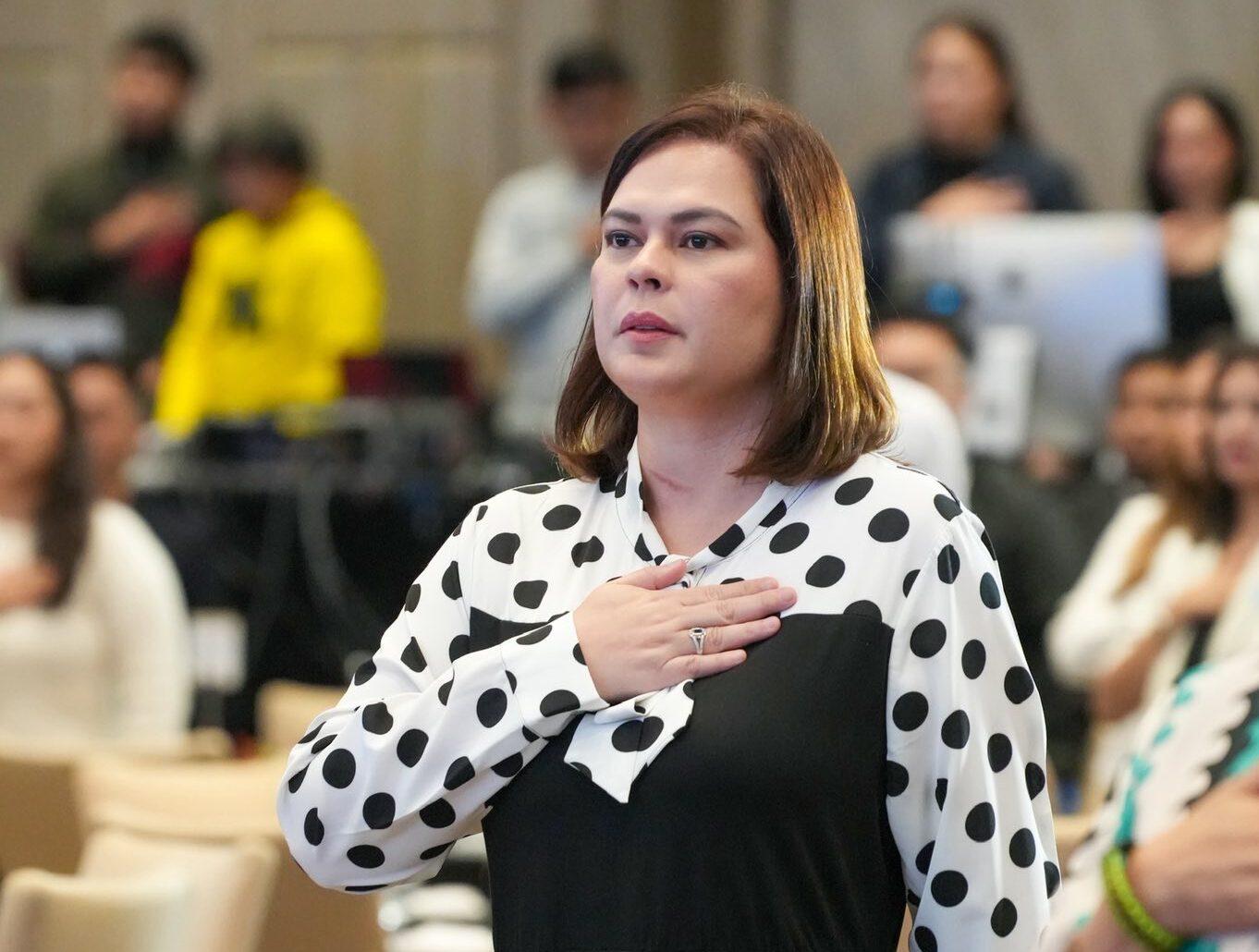

MANILA, Philippines – Vice President Sara Duterte, the 47-year-old daughter of former president Rodrigo Duterte, entered February facing three impeachment complaints at the House of Representatives.

Two of these filings involve Catholic priests and religious sisters among the complainants, as well as a Christian pastor.

Under the constitution of the Philippines, an impeachment complaint may be filed by any member of the House of Representatives or by any citizen upon a resolution or endorsement by any House member. If the House votes to impeach, a trial may proceed before the Senate. There are, however, procedural hurdles and political realities with which to contend, as recent history shows.

Sara Duterte was impeached in early 2025 after the House of Representatives received complaints late the previous year, but the Senate sent the articles back to the House and the Supreme Court subsequently intervened to say the complaint was unconstitutional, barring any further action until early February of 2026.

“We believe this is a moral duty for us, as priests and religious,” Father Joselito Sarabia told journalists, explaining why they filed the third impeachment complaint on Monday.

They accused the Vice President of misusing around $10.5 million in discretionary funds, meant to be used for confidential expenses such as surveillance activities.

They also allege that Duterte plotted to assassinate President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., First Lady Liza Araneta-Marcos, and the President’s cousin, former House Speaker Martin Romualdez.

Remarks by Duterte during a press briefing on November 23, 2024, gave rise to that allegation.

In the briefing, recordings of which circulated online widely at the time, Duterte cursed at Marcos – whom she identified by his initials, BBM – and said: “I have contracted a person. I told the person that if I am killed, you should kill BBM, Liza Araneta, and Martin Romualdez. No joke. No joke. I have given instructions.”

Similar accusations against Duterte could be found in the second impeachment complaint filed against her on February 2, which included two priests and one religious sister among the 18 complainants in total.

If Duterte is impeached by the House and later convicted by the Senate, she will be removed as Vice President and disqualified from public office, which would mean she could no longer run as president in the 2028 elections.

Duterte is popular, however, and has been polling as the front-runner in recent surveys.

The prospect of another Duterte presidency has alarmed Church leaders, activists, and journalists whom the elder Duterte attacked during his term.

Emphasizing that Duterte’s impeachment involves a moral concern, Sarabia added, “We are saying to our children: ‘It’s not right to steal, it’s not right to lie’.”

In filing the third impeachment complaint, the priests and religious were accompanied by Representative Leila de Lima, 66, who calls the elder Duterte her “chief persecutor.”

A critic of President Rodrigo Duterte’s drug war, De Lima was detained for nearly seven years after the Duterte government filed drug trafficking charges that were eventually dismissed.

De Lima said Sarabia and the other priest-complainants were her spiritual advisers when she was jailed. She defended them from the vice president’s claim that the impeachment complaints were a form of “political harassment.”

De Lima said the complainants are private citizens who have long campaigned for accountability among public officials including the Vice President. She told reporters their motivation is “not at all political” but rather involves a moral aspect.

Speaking with Crux, Sarabia recounted the prayerful atmosphere ahead of the filing of the third impeachment complaint. He cited the religious sisters who provided the process “a level of spirituality.”

“The sisters were repeating and continually praying, ‘O Mary, conceived without sin, pray for us who have recourse to you’,” Sarabia said, recalling their seven-minute walk from De Lima’s room to the office where the complaint was to be received.

The sisters told Sarabia they were teary-eyed and “really touched.”

“We are really praying that the country would be delivered from evil,” said Sarabia, a Vincentian priest who is now assigned to a poor community.

“It’s a moral imperative to fight evil,” Sarabia explained. “Our group thinks that the Duterte camp is the manifestation of that evil, as of now, here in the country.”

Like many Catholic leaders, Sarabia fears a Sara Duterte presidency, which, if she emerges victorious, would last for six years.

“I think it is very dangerous for her to be President,” Sarabia said. “She might even be worse than her father,” he said.

Human rights groups say some 30,000 people were killed in the government’s “war on drugs” during the presidency of her father, Rodrigo Duterte, who was also known to attack the Catholic Church, threatening to kill bishops, cursing at Pope Francis, and calling God “stupid.”

Key leaders of the Catholic Church, including Cardinal Pablo Virgilio David, were not spared from President Duterte’s tirades. David, who is bishop of Kalookan diocese, received the red hat from Francis in 2024.

Along with the memory of the late dictator Ferdinand E. Marcos, President Rodrigo Duterte’s attacks on the Church prompted the Catholic hierarchy to campaign against the Marcos-Duterte tandem in the 2022 election.

Hundreds of priests and bishops wore pink — the color of opposition candidate Leni Robredo — in an election that was framed as a battle of good versus evil.

Despite warnings of the Church hierarchy, this Catholic-majority country elected the Marcos-Duterte tandem in 2022. Marcos and Duterte, in fact, won with the highest share of votes since Philippine democracy was restored in 1986 after the 14-year Marcos dictatorship.

In electing them, Marcos and Duterte supporters cited the failure of politicians to make the Philippines prosper after the 1986 People Power Revolution, the Church-backed uprising that toppled the dictator Marcos. According to analysts, disinformation on social media also played a role in revising history and cleansing the Marcos and Duterte names.

Now that Marcos and Duterte are bitter enemies, the Philippine Catholic Church finds itself in a delicate place.

One criticism is that Catholic priests and religious have been treating Marcos, who also faces a corruption controversy, with kid gloves compared to Duterte.

Marcos is accused of involvement in multi-billion-peso flood-control mess, often described as the biggest corruption scandal in Philippine history.

To give an idea of the scale of the scandal, then-finance-secretary Ralph Recto told lawmakers late last year that 118.5 billion pesos ($2 billion) in funding for flood control in the flood-plagued nation may have been lost to corruption over the previous two years.

Recto is now serving as the country’s interim executive secretary, a cabinet-level position in some ways akin to a chief-of-staff and informally styled “little president” because of its sweeping authority.

Two impeachment complaints had earlier been filed against Marcos, but these were dismissed by his allies in Congress.

Sarabia, who had harshly criticized Marcos before his presidential term, said he is aware of the Marcos government’s involvement in many issues, but the Dutertes demonstrate to him a “clear and present danger.”

At the same time, according to Sarabia, the Philippines is better off under Marcos “to an extent” — and “at least, there are not as many killings.”

“We cannot catch two rabbits at the same time. Let’s put the Dutertes first,” he said. “If the Dutertes return, we are back to zero.”

Father Robert Reyes, an activist priest who joined the second impeachment complaint, said he is “not absolving” Marcos by running after Duterte first.

He said that Marcos will face his time of reckoning, but “between Marcos and the Dutertes, at this point of our history, we can deal with a benign Marcos leadership, but we cannot tolerate a Duterte comeback.”

“There is no absolution, but there is a toleration,” said Reyes in an interview with Crux.

“Obviously, we are tolerating a lesser evil, which is still an evil, but a greater evil threatens to return and destroy our democracy,” Reyes said.

“Dealing with both and trying to exact justice from both, at the same time,” he said, “will not work in favor of everyone else.”