Given what a cancer the clerical sexual abuse scandals have been for the Catholic Church, one would imagine the Vatican would want new bishops to get a state-of-the-art presentation on best practices in terms of preventing such meltdowns in the future.

The Vatican has been running just such a training course since 2001 for newly appointed bishops around the world, and almost 30 percent of the Catholic prelates in the world today have taken it.

It’s more than a bit surprising, therefore, to discover that at least last year, the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors, the body created by Pope Francis to identify “best practices” in the fight against child abuse, was not involved in the training.

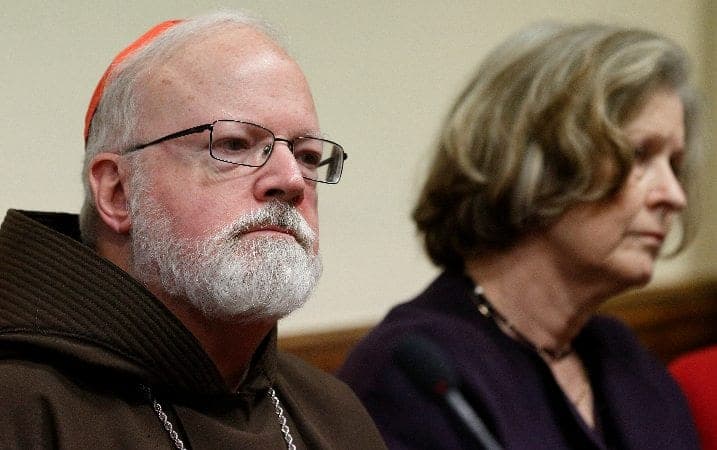

What’s the point of creating a commission to promote best practices, and putting one of the Church’s most credible leaders on the abuse issue, Boston Cardinal Sean P. O’Malley, in charge of it, and yet not having it address the new leaders who will have to implement those practices?

On Monday, the top official at the Congregation for Bishops, Canadian Cardinal Marc Ouellet, outlined the papers presented during the most recent course, saying he wanted to invite “suggestions for improving the experience.”

Traditionally, bishops have three key tasks: sanctifying, teaching, and governing. New bishops need to hear something about each, but on governance, a preeminent place clearly should go to the fight against child sexual abuse. Ouellet acknowledged it, listing “prevention of abuses” among key challenges.

In that light, it’s worth reviewing what new bishops were, and weren’t, told.

The presentation was entrusted to French Monsignor Tony Anatrella, a consulter to the Pontifical Council for the Family and the Pontifical Council for Health Care Workers, who’s based at the Collège des Bernardins in Paris. He’s a psychotherapist controversial for his views on homosexuality and “gender theory.”

Although his presentation was long on therapeutic analysis, Anatrella did a credible job of slogging through components of the Code of Canon Law governing clergy accused of sexual crime with a minor.

In other ways, however, his presentation seemed seriously wanting. For instance, Anatrella argued that bishops have no duty to report allegations to the police, which he says is up to victims and their families. It’s a legalistic take on a critical issue, one which has brought only trouble for the Church and its leaders. Why, one wonders, was it part of a training session?

Most basically, canonical procedures kick in only after abuse has been alleged. Presumably the goal ought to be to stop those crimes from happening, and in that regard it’s striking that Anatrella devoted just a few paragraphs to abuse prevention, using abstract language without concrete examples.

It’s especially puzzling given the resources the Church has invested in prevention programs. In the United States, the bishops estimated in 2013 that they had spent $260 million since 2002. A new book called “The Whole Truth” by Chicago-based attorney Joe Klest, an agnostic who’s made millions suing the Church on behalf of abuse victims, praises those efforts.

“We need to focus on the protection of our children, the prevention of abuse, and swift intervention when abuse occurs,” Klest writes, referring to all of society. “The fact is that the institution that’s done more to create a reforming model for doing that is the Catholic Church.”

For perspective, I contacted Monsignor Stephen Rossetti, who’s on the board of the Rome-based Gregorian University’s Centre for Child Protection, to ask, “What should new bishops be told about sexual abuse?”

Here’s what he said bishops need to know:

- 1. “How to deal with victims, because it’s not intuitively obvious.”

- 2. “They have to know the canonical material.”

- 3. “What the red flags [for abuse] are … It’s important to be concrete, giving scenarios and talking out what an effective response looks like.”

- 4. “How to deal with accused priests … including the risk of recidivism, as well as how to show charity without enabling abusive behavior.”

- 5. Abuse prevention resources: “We don’t have to start from scratch. There are effective programs available right now.”

Judging by the published papers, only the second point figured prominently in the “baby bishops” program last year.

The omissions raise an obvious question: Why is the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors, the body led by O’Malley, not entrusted with making such a presentation to new bishops?

That commission took a hit on Saturday when one of two members who are also abuse survivors, Peter Saunders, was given a leave of absence amid his bitter complaints about the pope’s response to several recent controversies. Yet its raison d’être remains identifying best practices in prevention, detection, and response; its officials have made presentations to bishops’ conferences around the world to share that experience.

The next course for new bishops will be held in early September. In parallel fashion, the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples, responsible for bishops in mission territories, holds its own program. It’s hard to see why the commission wouldn’t be invited to both.

If the Church is to recover from the abuse scandals, bishops need every tool available, and these courses provide a chance to equip them. It would be a shame, to say the very least, not to take full advantage.