In order to truly understand this election, we have to look backward.

No, not in a reactionary way. Rather, we need to study the past because republics—and human beings—have faced batty, crude, and even alarming periods before. Nothing is new.

So how far should we go? Rome? Let’s try 19th-century France and pull a figure from it: Emmanuel d’Alzon, founder of the Augustinians of the Assumption.

D’Alzon’s time was much like our own. In an 1835 letter to Alphonse de Vigniamont, a friend, d’Alzon discussed the importance of ideas and education in shaping human character, a truth already beginning to fade. His thoughts are worth quoting at length:

“The more I look at the world from this point of view, the more I am disgusted with politics, which I consider to be a dead end. There is no life there, only death convulsions, powerless attempts to organize, vain efforts, unless Catholic thought penetrates it with charity, justice, and the spirit of Christian liberty, which regardless of what they say is completely suffocated in our day. I have made up my mind, and it is confirmed each day as I read the second psalm, which I urge you to meditate.

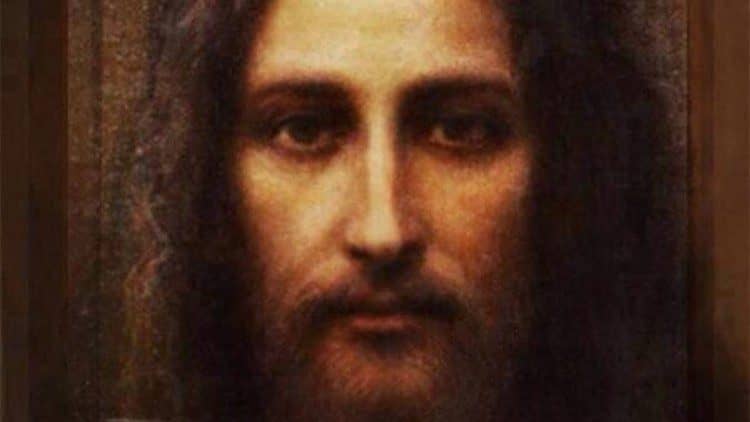

“I am convinced that both the people and the kings are at fault; let them chasten each other. It is clear to me that what the priest must do is work with whatever strength he has to establish the reign of Christ without getting lost in useless arguments. His king is Jesus of Nazareth; his tribunal, Calvary; his flag, the cross. Attach no color to this flag; the cross that Jesus hung upon, the one that appeared to Constantine was neither red nor white, and yet the former saved the world, and the latter conquered it.

“The most intimate thought of my soul is that the world needs to be penetrated through and through by a Christian idea; otherwise it will fall apart. And the world will not receive this idea but from men who will be taken up with it before all else in order to proclaim it in every form that it might assume. They say the world is evil. No doubt, passion turns it away from what is good. But I believe most of all that the world is ignorant. Therefore, we need to teach it and to do so in words it can understand.”

In this passage, d’Alzon declares himself “disgusted with politics,” something he finds to be a “dead end.” Kings and people are at fault for the way things are; they continue to “chasten each other.” Political life is a misnomer: it doesn’t exist. In it are “only death convulsions, powerless attempts to organize,” all of which are vain.

This doesn’t sound too different from our current election, with its constant, angry soundbites, its candidates’ aggressive attacks, its riled-up supporters, many of whom have taken to conspiracy theories instead of facts. We’re all chastening each other. In consequence, we’re on our way to becoming a hard people.

We can blame many different things—ideological partisanship, poor education, job losses, classism—and all of them hold some merit, but what d’Alzon would likely say about our time is we’ve forgotten about formation.

What does it mean to be formed? Exactly what you’d imagine: developed into a serious, self-giving human being, one who has learned to moderate his passions and direct them toward the good, the true, and the beautiful.

But we don’t teach people this anymore. Our schools, with some exceptions, of course, are really nothing more than rubber-stamping facilities—apologies to teachers: this has nothing to do with you; it’s the way we conceive of education today—that send people from grade to grade and then to college, where students earn degrees that have become tickets into middle-class life.

And at home and at work, we spend most of our time distracted by entertainments.

So, as a consequence, our passions run wild and we, consciously or not, become interested in half-formed ideas, because we need to satiate our internal longing for truth, the same one that drove Augustine from his life of debauchery into a life of philosophical and theological exploration.

This is why, in 2016, we have the election we have. But d’Alzon didn’t give up in the 19th century, and neither should we. As he pointed out, people are merely ignorant of the truth and need to be taught it.

Truly, human life and all its components—the political, economic, the trivial—is one of ideas. They shape us. They can make us into our best or our worst selves. d’Alzon believed the Christian idea, which led a revolution 2,000 years ago and hasn’t stopped since, should “penetrate” the world through and through, showing us the meaning of “charity, justice, and the spirit of Christian liberty.” Otherwise, things will fall apart.

We shouldn’t become apocalyptic, however. Nor is this a call to making things great again, as one of our candidates so often puts it. But it is a reminder that the tools to live well already exist. We should heed them.

Jonathan Bishop is Vocation Coordinator for the Augustinians of the Assumption in the Boston, Mass., area.