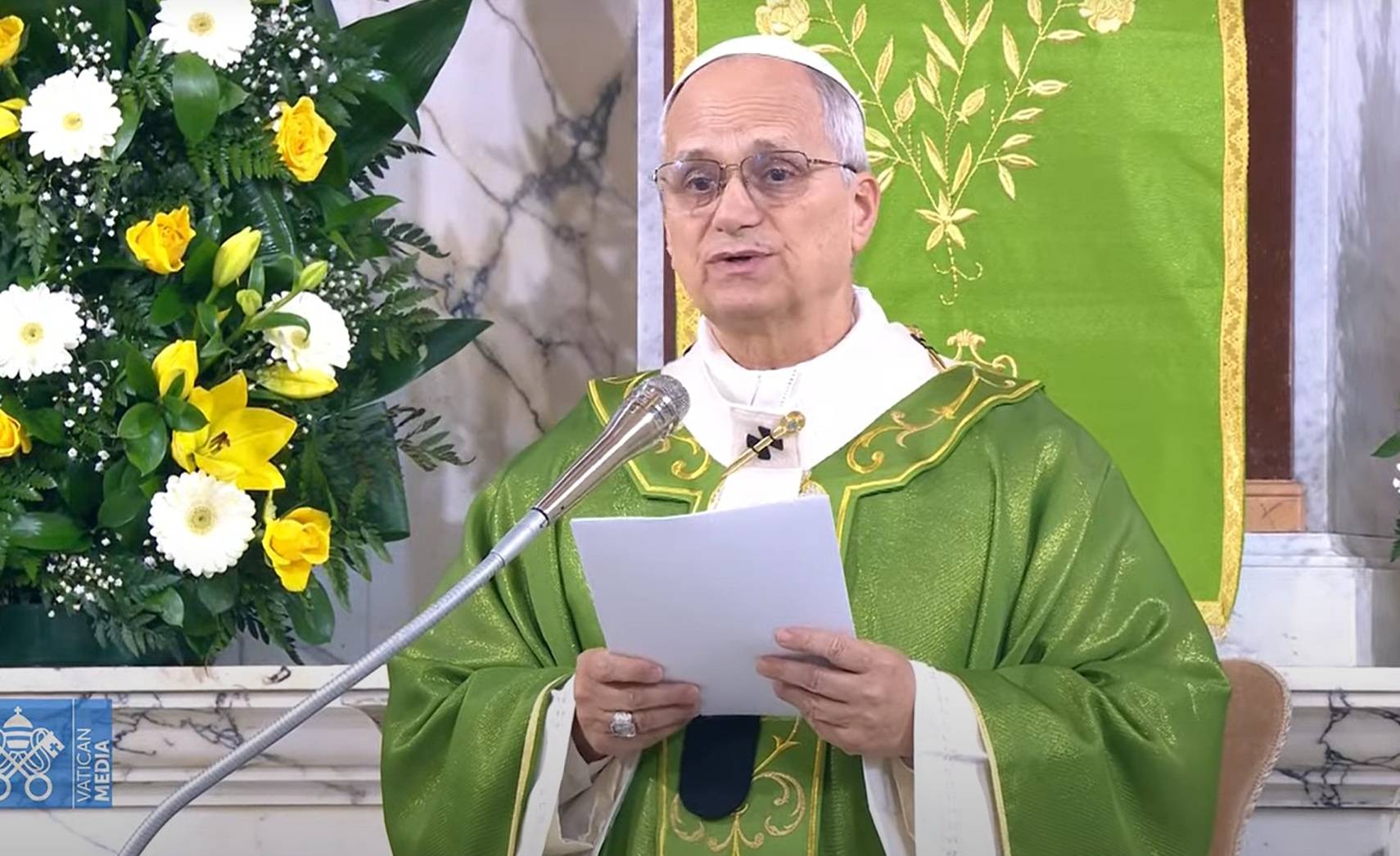

On Sunday, just ahead of his trip to Türkiye and Lebanon, Pope Leo XIV wrote about the 1700th Anniversary of the Council of Nicaea, which is the reason for his journey.

The pontiff says the Council still a significant role to play in the future of Christian unity.

The Council of Nicaea battled the Arian heresy, which denied that Jesus was God.

In his letter, titled In Unitate Fidei (“On the unity of faith”), Leo discusses how the controversy that ensued over Arius’ views – which gained a great deal of traction – precipitated “one of the greatest crises in the Church’s first millennium.”

The reason for the dispute “was not a minor detail.”

It is why the Nicene Creed contains language precisely expressing what the Church believes about Jesus Christ: “I believe in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Only Begotten Son of God, born of the Father before all ages. God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, consubstantial with the Father; through him all things were made.”

Every Sunday, Catholics say this at Mass – although admittedly many do not think about them too much.

“The Fathers of Nicaea were firm in their resolution to remain faithful to biblical monotheism and the authenticity of the Incarnation,” Leo writes in his letter. “They wanted to reaffirm that the one true God is not inaccessibly distant from us, but on the contrary has drawn near and has come to encounter us in Jesus Christ,” Leo also writes.

The pope says the 1700th anniversary “is relevant today because of its great ecumenical value.”

“Exactly thirty years ago, Saint John Paul II further promoted this conciliar message in his Encyclical Ut Unum Sint. In this way, together with the great anniversary of the First Council of Nicaea, we also celebrate the anniversary of the first ecumenical Encyclical. It can be considered a manifesto that brought up to date the same ecumenical foundations laid down by the Council of Nicaea,” Leo writes.

“The restoration of unity among Christians does not make us poorer; on the contrary, it enriches us. As at Nicaea, this goal will only be possible through a patient, long and sometimes difficult journey of mutual listening and acceptance,” the pope says.

This is interesting, because Leo spends a lot of writing in In Unitate Fidei about how the dispute over the Arian heresy was anything but a “journey of mutual listening and acceptance.”

“As we have already said, Nicaea clearly rejected the teachings of Arius. However, Arius and his followers did not give up,” the pope writes. “The Emperor Constantine himself and his successors increasingly sided with the Arians. The term homooúsios became a bone of contention between the Nicene and anti-Nicene factions, thus triggering other serious conflicts.”

Leo noted Saint Athanasius became the firm foundation of the Nicene Creed through his “unyielding and steadfast faith.”

“Although he was deposed and expelled from the Episcopal See of Alexandria five times, he returned each time as bishop. Even while in exile, he continued to guide the People of God through his writings and letters,” he writes.

For over a century, Arianism continued to be held by many in the Church, and led to several other ecumenical councils (some of which were rejected by Churches that accepted Nicaea.)

The pope omits mention of the fact that fistfights occurred with some frequency at these meetings.

Although Leo pointed out that in the 16th century, Nicaea was upheld by the Protestant churches brought about by the Reformation, he failed to mention that many of the churches formed in the 19th century – the so-called “restoration churches” including the Unitarian churches and most Pentecostal churches reject the Creed.

Another reality is that many Christians accept the Creed in name only – especially the idea that Jesus Christ is really fully God, with some saying they are okay with the title “Son of God”, but less comfortable with the idea of “God the Son.”

As one Vatican official once said at a dinner I attended, “Most modern Christology would make Arians blush.”

There are even Catholic theologians who question what “the historical Jesus” is able to know, and this issue hits even harder in many of the denominations associated with World Council of Churches (WCC), the main international ecumenical body.

Historically, this view was held by a group known as the Agnoetae – from the Greek word for “unknowing” – and was condemned by Pope Gregory I in 599.

If you ever read anything which suggests Jesus “hid himself” from his Divine knowledge – for example, he didn’t know something that a neighbor knew or where something was – that would be an example of the Agnoete heresy.

And this is a rather common kind of thing people hear more and more, especially in official ecumenical quarters.

An interesting pathway of Christian unity is now taking place online, too. People not particularly interested in ecumenical conferences are debating each other in the tried-and-true, millennia-old manner – by calling each other heretics. More and more adults are becoming Catholic because of arguments they are seeing on YouTube or other online websites. Thankfully, this doesn’t include the violence that often accompanied the controversies of centuries past.

Sadly, many of the champions of Catholicism have little training and are often abrasive, their theological takes given over cigars and between disquisitions on the virtues of bodybuilding, and sooner or later shouted.

Nevertheless, officials in the Catholic Church may need to start taking notice.

“It is a theological challenge and, even more so, a spiritual challenge, which requires repentance and conversion on the part of all,” Leo notes in his latest letter. That “challenge” might be more “challenging” than he knows.

Follow Charles Collins on X: @CharlesinRome