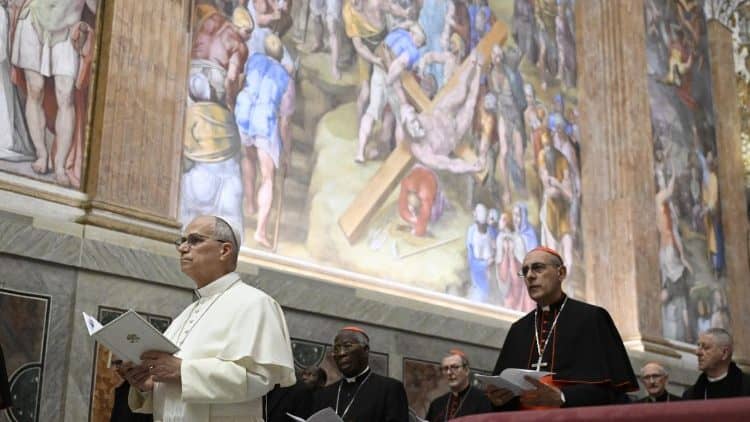

Pope Leo XIV met with a group of fifteen victims of clerical sexual abuse on Saturday. All from Belgium, the fifteen victims suffered their abuse when they were minors. Many of them had participated in a meeting with Pope Francis during his September 2024 visit to the country.

A statement from the press office of the Holy See sent to accredited journalists early Saturday evening said the encounter lasted “nearly three hours” and unfolded “in a climate of closeness with the victims, of listening and dialogue, both profound and painful.”

A report from the official Vatican News outfit said members of the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors accompanied the victims on Saturday evening, after meeting with them separately earlier in the day to continue a dialogue begun in July, when a PCPM delegation visited Belgium.

A plea for patience

On Tuesday of this past week, Pope Leo XIV asked victims of clerical abuse for patience as the wheels of justice turn. It was a startling request, for its frankness and its hopefulness. It was also a very big ask – much bigger even than the shock of it suggests – for several related reasons.

“I know it’s very difficult for the victims to ask that they be patient,” Leo told waiting journalists on Tuesday evening outside the papal residence in Castel Gandolfo, “but the church needs to respect the rights of all people.”

“The principle of innocent until proven guilty is also true in the Church,” Leo said.

The pontiff was not wrong in what he affirmed, but in order to understand how jarring were his remarks – to victims especially but not exclusively – it is important to know that he was responding to a question about a notorious celebrity-artist who escaped justice for decades and is still a priest in good standing, apparently in full possession of his priestly faculties despite the charges against him.

The specific context of Leo’s remarks is at least as important as the remarks themselves, in other words, and the victims to whom Leo addressed his remarks specifically have good reason to doubt the wheels of justice are turning at all.

Remarks in context: The Rupnik Affair

Leo was responding to a journalist’s question regarding the case of Father Marko Rupnik, a Slovenian priest and former Jesuit now incardinated in the Koper diocese of his native country but reportedly residing in Rome.

Rupnik is accused by multiple witnesses – “highly credible” to hear the Vatican’s own investigator tell it – of serial spiritual, psychological, and sexual abuse against dozens of victims, most of them women religious (of whom several belonged to a religious congregation Rupnik helped establish in his native Slovenia), over a period of some three decades, much of it under the noses of his erstwhile Jesuit superiors.

Rupnik grew to worldwide renown during the course of what is credibly alleged to be his inveterately abusive career, as a mosaic artist and spiritual master very much in demand as a speaker and retreat leader, while powerful men in the Jesuit order and in the Vatican either turned a blind eye to complaints against him or else – as is also alleged – actively worked to discredit his accusers.

Rupnik’s accusers, in short, have been patient for decades. So have other victims everywhere in the world. It is certainly the case that Leo XIV inherited an unholy mess from his predecessor, especially insofar as the Rupnik Affair is concerned. Rupnik’s accusers, and victims in general, may be forgiven the impression the pope’s words presumed a greater store of patience than it is reasonable to expect, even if they did not mean to suggest impatience either on the part of victims or the scandalized faithful.

Fear and favor

A frequent – and by every measure reasonable – complaint is that Rupnik has received extraordinarily favorable treatment, both from his erstwhile superiors in his former Society of Jesus and from Vatican officials including Pope Francis.

Francis had Rupniks in his residence and once used a Rupnik as a prop in a video message to participants in a Marian conference in Aparecida, even after grim details of Rupnik’s case had become public knowledge.

“When an individual is credibly accused of very serious offenses like those of which Marko Rupnik is accused,” survivor-advocate Antonia Sobocki of the UK-based LOUDfence advocacy group told Crux, “under law in the UK, they are held on remand in prison awaiting trial.”

“This is not a presumption of guilt,” Sobocki said, “but an act of due diligence in order to protect the public.”

“To permit an individual credibly accused of such actions to remain free in a community is not a neutral act,” Sobocki said. “It puts the innocent at risk.”

The Society of Jesus expelled Rupnik in 2023 – for disobedience, not as punishment for his alleged crimes – and the former Jesuit quickly found a diocese in his native country willing to take him as a priest.

RELATED: Connecticut Catholic apostolates wrestle with fate of Rupnik artwork

Rupnik even preached the Lenten retreat to the Roman Curia in 2020 – generally recognized as the highest honor any preacher can receive – after a secret panel of investigators had secretly determined Rupnik had “absolved an accomplice in a sin against the Sixth Commandment” i.e. given sacramental absolution to someone with whom he had illicit sexual relations of some sort. Later, secret judges would secretly impose and then secretly lift an excommunication.

The Jesuits would secretly impose restrictions on Rupnik, who not-so-secretly flouted them, rightly surmising that his erstwhile superiors would be reluctant to enforce them and that the Vatican would rather the whole business remain under wraps. He trotted the globe giving talks, cutting ribbons, and collecting accolades.

It would take an entire book to recount all the gruesome twists and turns of the impossibly macabre Rupnik story, so suffice it to say the disgraced Slovenian former Jesuit very nearly got away with it, not without some inexplicable decisions by several very senior churchmen, including Pope Francis.

Justice delayed

Eventually, Francis decided – under sustained pressure from his own Commission for the Protection of Minors and in the face of incandescent global outrage – to waive the statute of limitations and allow a case against Rupnik to proceed. That was in 2023, more than four years after the case had officially reached the Vatican (decades after allegations began to circulate in Jesuit and Vatican circles in Rome and elsewhere) and nearly a year after the story had come before the public.

When Francis died, the Discipline Section of the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith was still trying to find judges to hear the case. It was Oct. 13 of this year that the Vatican announced a full slate of five judges had finally been empaneled to try Rupnik.

RELATED: Rupnik case casts shadow on Vatican’s commitment to fight abuse

Rupnik’s work – frequently decried as “rape art” by victims and advocates – continues to be the subject of calls for removal from victims, their advocates, and the scandalized faithful.

RELATED: Vatican comms chief defends use of accused sexual abuser’s artwork

RELATED: Vatican website removes pictures of artwork created by priest accused of abuse

The scales of justice

Stepping back from the narrow question of what to do about Rupnik’s art, observers also note a stark discrepancy between the way Pope Francis and the Vatican treated Giovanni Angelo Becciu – a cardinal accused of financial malfeasance – and the treatment Rupnik has received. Francis forced Becciu to resign his high-ranking Vatican position and stripped him of his rights as a cardinal before formal charges were even brought, then changed Vatican City law to allow a trial in Vatican City criminal court to proceed against him.

The trial court convicted Becciu, who has always maintained his innocence and is currently appealing his conviction. The Vatican did not appear to have any difficulty finding judges for either process.

Since his election, Pope Leo XIV has been spending the early part of his working week at the summer retreat outside Rome, frequently leaving the Vatican on Monday to return Tuesday evening, and he has a lot to think about.

The unfinished business of the Rupnik Affair – frequently viewed as a microcosm of Church leaders’ inveterate inability to get a handle on the crisis of abuse and coverup – is largely the result of Leo’s predecessor’s penchant for putting his finger on the scales of justice.

From the outside looking in, it appears that churchmen – including the Pope, at least in the recent past – have been willing to move heaven and earth to secure a conviction against a cardinal accused of stealing money, but will drag their feet, or worse, to ensure abusers never see justice.

Neither Leo XIV nor any other leader can fix that problem by putting his own finger on the same scales.

That, in a nutshell, is why Leo’s answer made news after a journalist – it was Magdalena Wolinska-Reidi of EWTN News, for the record – noted how “[s]ome abuse survivors say, and their advocates as well, say that the presence of Father Rupnik’s art in important churches and shrines, including the Vatican, all over the world, are traumatic for them and for many other people, also scandalous,” and asked: “How can the Church be sensitive to their requests to perhaps cover these pieces of art, or even to remove them?”

The state of the question

“Certainly,” Leo said, “in many places, it’s precisely because of the need to be sensitive to those who have presented cases of being victims, the artwork has been covered up.” One such place is the healing shrine of Lourdes. In other places, including the Vatican, Rupniks are still adorning sacred space.

“Artwork has been removed from websites,” Leo also said, fairly taken as an allusion to the Rupniks’ quiet disappearance from the Vatican’s digital pages, “so, that issue is certainly something that we’re aware of.”

“A new trial has recently begun,” Leo continued, noting the appointment of judges and acknowledging how “processes for justice take a long time.”

“[H]opefully,” Leo said, “this trial that is just beginning will be able to give some clarity and justice to all those involved.”

If those responsible for shrines and chapels where Rupniks are present wish to cover or remove the works, that is their business. The upset and scandal of the whole affair is galling, indeed, not only to victims.

Leo could order the Rupniks in the Redemptoris Mater chapel covered, but doing so would inevitably – and quite reasonably – be understood as an act taken with a view to influencing a high-profile trial, to the outcome of which he must remain officially and effectively indifferent.

Even if Leo’s intentions were pure as the driven snow, the act itself would affect public opinion and quite possibly influence judges’ discernment.

The most important thing Pope Leo can do in the Rupnik case is to ensure that justice be done, and that it is seen to be done.

Still, justice delayed is justice denied, and justice in the Rupnik case has been delayed for far too long. For countless victims of clerical abuse, patience is running out.

Follow Chris Altieri on X: @craltieri